Funk’s advent was the result of a convergence of many musical events, a “perfect storm” precipitated by the coalescing of all the major postwar African-American musical forms, among them jazz, blues, r&b, and gospel. Like many other innovations in American popular music, it came into its own in the ’60s. Its evolution can be heard in the output of musicians from just about every major US city, but Detroit, Philadelphia, Memphis, and New Orleans (see below) were the real hotbeds of activity. But if there is one individual who can be seen as the form’s prime architect, it’s a man from Macon, Georgia by the name of James Brown. Accentuating rhythm above all else, and essentially making his backing band, the Famous Flames, a massive percussion instrument, the Godfather laid the groundwork for The Groove. This proto-Funk sound exists in some shape or form on just about all of his King Records releases from Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag onwards. But many of his peers were also throwing down. Here’s a short list.

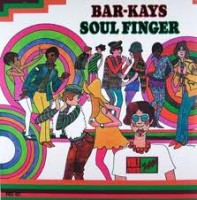

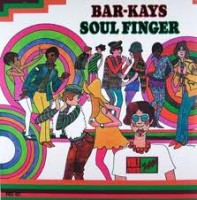

1. The Bar-Kays Soul Finger (1967) Though there are other great tunes in this assortment of instrumentals, its title track, with its thumping bass and blasting horns, is deservedly the standout. Even the record’s unavoidable association with one of the greatest tragedies in Soul music history—it’s the only one the original lineup recorded before three of its members perished with Otis Redding in a plane crash—can’t detract from its joyous groove.

1. The Bar-Kays Soul Finger (1967) Though there are other great tunes in this assortment of instrumentals, its title track, with its thumping bass and blasting horns, is deservedly the standout. Even the record’s unavoidable association with one of the greatest tragedies in Soul music history—it’s the only one the original lineup recorded before three of its members perished with Otis Redding in a plane crash—can’t detract from its joyous groove.

2. Sly and the Family Stone Dance to the Music (1968) This sophomore effort by the Bay Area psychedelic soulsters is where they really find their footing. Much more of a group effort than Sly’s later work, its melding of fuzzed-out guitar, stinging brass, life-affirming vocals, and the stellar basswork of one of funk’s greatest innovators, Larry Graham, ushered in a new era.

2. Sly and the Family Stone Dance to the Music (1968) This sophomore effort by the Bay Area psychedelic soulsters is where they really find their footing. Much more of a group effort than Sly’s later work, its melding of fuzzed-out guitar, stinging brass, life-affirming vocals, and the stellar basswork of one of funk’s greatest innovators, Larry Graham, ushered in a new era.

3. The Meters (1969) – No other city is as deserving of the title “The Cradle of Funk” as New Orleans. In the late ’60s, literally hundreds of artists in that city cooked up potent stews of tight grooves and fat beats, and the Meters were the undisputed head chefs. Their Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn-produced debut features a smoking collection of instrumentals, including the original version of “Cissy Strut”, now a Funk standard.

3. The Meters (1969) – No other city is as deserving of the title “The Cradle of Funk” as New Orleans. In the late ’60s, literally hundreds of artists in that city cooked up potent stews of tight grooves and fat beats, and the Meters were the undisputed head chefs. Their Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn-produced debut features a smoking collection of instrumentals, including the original version of “Cissy Strut”, now a Funk standard.

4. Eddie Bo and the Soul Finders The Hook and Sling (1997) Elsewhere in the Crescent City, this prolific national treasure, whose output spanned from the early 50s to just a few months before his death in 2009, unleashed one of early Funk’s catchiest numbers, “The Hook and Sling”—a sizable hit on the R&B charts in 1969. Every bit as much of an innovator as his peers, Bo unfortunately remained in their shadows for most of his career. Even stranger, he never managed to cut a full-length LP during this, his most important, period. This 1997 compilation serves as the next best thing.

4. Eddie Bo and the Soul Finders The Hook and Sling (1997) Elsewhere in the Crescent City, this prolific national treasure, whose output spanned from the early 50s to just a few months before his death in 2009, unleashed one of early Funk’s catchiest numbers, “The Hook and Sling”—a sizable hit on the R&B charts in 1969. Every bit as much of an innovator as his peers, Bo unfortunately remained in their shadows for most of his career. Even stranger, he never managed to cut a full-length LP during this, his most important, period. This 1997 compilation serves as the next best thing.

5. Charles Wright and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band Express Yourself (1970) Seminal release by Charles Wright and the best incarnation of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band. [Read full review here!]

5. Charles Wright and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band Express Yourself (1970) Seminal release by Charles Wright and the best incarnation of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band. [Read full review here!]

Further listening: Let’s face it: Funk is really a singles medium. It’s an unfortunate fact that many records from its golden era were hastily thrown together affairs. A typical LP might contain one or two amazing tracks scattered amongst some lackluster mid-tempo numbers and cheesy ballads. (Yes, we’re talking about you, James Brown!) This is where one can be thankful for the modern miracle called the compilation. The music industry initially was slow to recognize it as a genre fit for this type of (re)packaging, but by the mid-90s stylishly packaged funk compilations were a common sight in even mainstream record stores. Many of these are riddled with overplayed hits, so one is advised to dig deep. The Brits seem to do them the best. The London-based Soul Jazz Records sets the gold standard for comps and reissues. Their three volume New Orleans Funk series is an essential intro to some of the best music from Funk’s early days. Similarly, BGP’s Superfunk series is uniformly great. –Richard P

1. The Bar-Kays Soul Finger (1967) Though there are other great tunes in this assortment of instrumentals, its title track, with its thumping bass and blasting horns, is deservedly the standout. Even the record’s unavoidable association with one of the greatest tragedies in Soul music history—it’s the only one the original lineup recorded before three of its members perished with Otis Redding in a plane crash—can’t detract from its joyous groove.

1. The Bar-Kays Soul Finger (1967) Though there are other great tunes in this assortment of instrumentals, its title track, with its thumping bass and blasting horns, is deservedly the standout. Even the record’s unavoidable association with one of the greatest tragedies in Soul music history—it’s the only one the original lineup recorded before three of its members perished with Otis Redding in a plane crash—can’t detract from its joyous groove. 2. Sly and the Family Stone Dance to the Music (1968) This sophomore effort by the Bay Area psychedelic soulsters is where they really find their footing. Much more of a group effort than Sly’s later work, its melding of fuzzed-out guitar, stinging brass, life-affirming vocals, and the stellar basswork of one of funk’s greatest innovators, Larry Graham, ushered in a new era.

2. Sly and the Family Stone Dance to the Music (1968) This sophomore effort by the Bay Area psychedelic soulsters is where they really find their footing. Much more of a group effort than Sly’s later work, its melding of fuzzed-out guitar, stinging brass, life-affirming vocals, and the stellar basswork of one of funk’s greatest innovators, Larry Graham, ushered in a new era. 3. The Meters (1969) – No other city is as deserving of the title “The Cradle of Funk” as New Orleans. In the late ’60s, literally hundreds of artists in that city cooked up potent stews of tight grooves and fat beats, and the Meters were the undisputed head chefs. Their Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn-produced debut features a smoking collection of instrumentals, including the original version of “Cissy Strut”, now a Funk standard.

3. The Meters (1969) – No other city is as deserving of the title “The Cradle of Funk” as New Orleans. In the late ’60s, literally hundreds of artists in that city cooked up potent stews of tight grooves and fat beats, and the Meters were the undisputed head chefs. Their Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn-produced debut features a smoking collection of instrumentals, including the original version of “Cissy Strut”, now a Funk standard. 4. Eddie Bo and the Soul Finders The Hook and Sling (1997) Elsewhere in the Crescent City, this prolific national treasure, whose output spanned from the early 50s to just a few months before his death in 2009, unleashed one of early Funk’s catchiest numbers, “The Hook and Sling”—a sizable hit on the R&B charts in 1969. Every bit as much of an innovator as his peers, Bo unfortunately remained in their shadows for most of his career. Even stranger, he never managed to cut a full-length LP during this, his most important, period. This 1997 compilation serves as the next best thing.

4. Eddie Bo and the Soul Finders The Hook and Sling (1997) Elsewhere in the Crescent City, this prolific national treasure, whose output spanned from the early 50s to just a few months before his death in 2009, unleashed one of early Funk’s catchiest numbers, “The Hook and Sling”—a sizable hit on the R&B charts in 1969. Every bit as much of an innovator as his peers, Bo unfortunately remained in their shadows for most of his career. Even stranger, he never managed to cut a full-length LP during this, his most important, period. This 1997 compilation serves as the next best thing. 5. Charles Wright and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band Express Yourself (1970) Seminal release by Charles Wright and the best incarnation of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band.

5. Charles Wright and the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band Express Yourself (1970) Seminal release by Charles Wright and the best incarnation of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band.

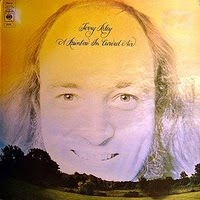

Future Holden Caufields, venturing out into the big bad city just two decades later, would have no need to feel so alienated — not with Central Park Be-Ins to take part in and Terry Riley’s A Rainbow In Curved Air providing the imaginary soundtrack. Riley’s LP – produced in ’67 once again by Music Of Our Time overseer David Berhman- is the most blatantly pop-friendly of all experimental albums up until Philip Glass’s Glassworks (the latter designed for an upscale yuppie audience which didn’t exist at the height of the Vietnam war.) No such compromises on Riley’s part–his loose, drony improvisations, heard here in gloriously overdubbed three dimensions, appealed to eager, young ears opened up by the raga craze and all sorts of other Eastern “space.” And despite his benign, hippie veneer, the composer didn’t neglect the dark side of Aquarius either, as the ominous psychedelic swirl of “Poppy Nogood & The Phantom Band,” with its dense overlay of reeds, organ and tape loops, demonstrates ad infinitum. –SS

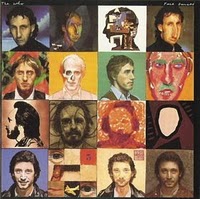

Future Holden Caufields, venturing out into the big bad city just two decades later, would have no need to feel so alienated — not with Central Park Be-Ins to take part in and Terry Riley’s A Rainbow In Curved Air providing the imaginary soundtrack. Riley’s LP – produced in ’67 once again by Music Of Our Time overseer David Berhman- is the most blatantly pop-friendly of all experimental albums up until Philip Glass’s Glassworks (the latter designed for an upscale yuppie audience which didn’t exist at the height of the Vietnam war.) No such compromises on Riley’s part–his loose, drony improvisations, heard here in gloriously overdubbed three dimensions, appealed to eager, young ears opened up by the raga craze and all sorts of other Eastern “space.” And despite his benign, hippie veneer, the composer didn’t neglect the dark side of Aquarius either, as the ominous psychedelic swirl of “Poppy Nogood & The Phantom Band,” with its dense overlay of reeds, organ and tape loops, demonstrates ad infinitum. –SS Excluding the classic rock radio staple “Eminence Front” from 1982’s “It’s Hard,” the eighties weren’t terribly kind to The Who. At the time of “Face Dances” release, fans were still mourning the loss of Keith Moon while punk and emerging new wave were stealing press space and radio air-waves. It’s difficult to imagine now how proto-punkers like The Who couldn’t have easily coexisted alongside The Clash, but at the time they were considered almost polar opposites. (Long time Seattleites might remember both camp’s negative reaction at that disastrous double bill in the Kingdome in ’82). Listening now, though, and judged on it’s own merits, “Face Dances” is surprisingly enjoyable and this underdog of an LP finds its way onto my turntable and ipod more often than “Who’s Next.” “Face Dances” is definitely not in league with the aforementioned classic but neither has it been played to death for the last twenty-five years. Also, I now prefer a introspective Pete Townshend even if Roger Daltry still delivers his words with all the gusto of “Baba O’Riley.” For anyone who’s written this one off, pick up the next 99¢ copy you see and give it a fresh listen the way you might approach a Townshend or Entwistle LP. Not only does it contain some of Townshend’s finest (Don’t Let Go The Coat) and oddest lyrical moments (Did You Steal My Money, Cache Cache), it features the “quiet” Entwistle’s least quiet moment, “The Quiet One” along with everyone’s favorite guilty Who-pleasure, “You Better You Bet” and the album closer’s lost gem, “Another Tricky Day.” –David

Excluding the classic rock radio staple “Eminence Front” from 1982’s “It’s Hard,” the eighties weren’t terribly kind to The Who. At the time of “Face Dances” release, fans were still mourning the loss of Keith Moon while punk and emerging new wave were stealing press space and radio air-waves. It’s difficult to imagine now how proto-punkers like The Who couldn’t have easily coexisted alongside The Clash, but at the time they were considered almost polar opposites. (Long time Seattleites might remember both camp’s negative reaction at that disastrous double bill in the Kingdome in ’82). Listening now, though, and judged on it’s own merits, “Face Dances” is surprisingly enjoyable and this underdog of an LP finds its way onto my turntable and ipod more often than “Who’s Next.” “Face Dances” is definitely not in league with the aforementioned classic but neither has it been played to death for the last twenty-five years. Also, I now prefer a introspective Pete Townshend even if Roger Daltry still delivers his words with all the gusto of “Baba O’Riley.” For anyone who’s written this one off, pick up the next 99¢ copy you see and give it a fresh listen the way you might approach a Townshend or Entwistle LP. Not only does it contain some of Townshend’s finest (Don’t Let Go The Coat) and oddest lyrical moments (Did You Steal My Money, Cache Cache), it features the “quiet” Entwistle’s least quiet moment, “The Quiet One” along with everyone’s favorite guilty Who-pleasure, “You Better You Bet” and the album closer’s lost gem, “Another Tricky Day.” –David