1973 was a good year for chilled out, soulful grooves. Along with Terry Callier’s masterpiece “What Color Is Love” we have Lucien’s best work “Rashida.” It could almost be a companion LP to Callier’s as it has a very similar vibe. It is a lushly produced collection of spaced out soul and folk that adds in elements of Latin music and a hint of Lucien’s Caribbean heritage. He has one of the best voices in music and its warmth gradually draws you deep into the record. Lucien never feels the need to show off or be flashy and he lets the strength of his lyrics do the work. Buy this and Callier and you will instantly improve your soul collection. –Jon

1973 was a good year for chilled out, soulful grooves. Along with Terry Callier’s masterpiece “What Color Is Love” we have Lucien’s best work “Rashida.” It could almost be a companion LP to Callier’s as it has a very similar vibe. It is a lushly produced collection of spaced out soul and folk that adds in elements of Latin music and a hint of Lucien’s Caribbean heritage. He has one of the best voices in music and its warmth gradually draws you deep into the record. Lucien never feels the need to show off or be flashy and he lets the strength of his lyrics do the work. Buy this and Callier and you will instantly improve your soul collection. –Jon

Album Reviews

Herbie Mann “Stone Flute” (1970)

One of the pleasures of working in a record store are those quiet weekday afternoons when you can randomly throw on forgotten records in hopes of unearthing a buried gem. Stone Flute is one of those gems. It’s also a far cry from the middle-of-the-road soul-jazz I generally associate with the furry Mr. Mann. (For all it’s guilty, funky pleasure, this is no Push Push. It’s one of the few records Mann recorded for his own Embryo labe, best known for its moody, trippy jazz and jazz-rock, and Stone Flute is no exception.

Standout tracks are the spacious, Eastern-inspired Donovan cover “In Tangier,” and the jaw-droppingly beautiful version of the Beatles’ “Flying,” which somehow manages to be even trippier than the original without sounding dated. If that wasn’t enough, the experimental “Miss Free Spirit” features jazz gods, Sonny Sharrock, Roy Ayers and and a pre-Weather Report Miroslav Vitous in top form. The album features lengthy, spacious arrangements that are difficult to digest properly with a quick listen, give it a thorough spin and you’ll discover a totally unique Herbie Mann record and one that any fan of late sixties/early seventies jazz will likely enjoy. –David

Demon Fuzz “Afreaka!” (1970)

Progressive rock in the ’70s was traditionally recognised as being the realm of white, occasionally nerdy, hippy-types. However, challenging such notions was the all black Demon Fuzz, who signed to Pye’s prog label, Dawn, in 1970.

Afreaka!, released in the same year was there one and only album. Five tracks pitch Demon Fuzz somewhere between prog rock and psychedelic soul-laced jazz excursions, with a threadwork of world music, tribal beats and the ever-trusty wah-wah pedal weaving its spell somewhere beneath. The opening instrumental of ‘Past, Present and Future’ begins in purest progressive rock style with the meandering showmanship of a grinding bass, prior to some sultry horns kicking in and the song taking on a psychedelic jazz /soul feel that wouldn’t sound out a place on the backing track to a 70s blaxploitation flick. It continues to blend styles for just shy of ten minutes, and amazingly, for a song that is both instrumental and of a jazz-influence, doesn’t get boring. The first of three vocal tracks, ‘Disillusioned’, keeps the jazz infusion ball rolling, through the faster paced ‘Another Country’, and leading to the eight minute long ’Hymn to Mother Earth’, a gently drifting paean to the ecosphere that bursts with dramatic interludes and is underscored by the prog rock weapons of choice, the organ (sounds like a Hammond) and flute.

Demon Fuzz’s blend is just right and succeeds in cooking up an appetising dish of progressive rock/soul/jazz/world fusion. One that’s well worth the more traditional progressive rock fan dipping their finger into. —Nick/Head Full of Snow

Stereo Laboratories: An Introduction to

Sound Library & Production Music

Discovering library music is a fascinating thing. This is music that was initially created for commercial purposes (created to be sold or licensed to film, television or radio). Library production music can be the most liberating, genre-bending musical experience, due to its lack of constraints on creativity. It varies from straight orchestral fare, bossa nova pop, quirky electro, disco, demented and moody electro-acoustics, folk, and everything else in between.

There were numerous labels of all shapes and sizes, mostly from France, Italy, Germany and the UK (L’illustration Musicale, de Wolfe, Telemusic, KPM, Selected Sound, Musique Pour l’Image, and Bruton being among some of the larger, more reknown labels), some with wide distribution, and others relegated to obscure status almost immediately. Composers would knock out several albums a month, often for different labels, and even more common, under a different name – leading to very difficult research, and a very tricky time for anyone trying to figure out any sort of discography trajectory. Some examples of aliases include the ever prolific Piero Umiliani, who also traded under Zalla, Moggi, Herbana, The Braen’s Machine (with Alessandro Alessandroni), and a few others. Nino Nardini was another big composer, getting his start in the 40’s as a big band jazz leader, soon becoming one of the towering figures in all of library music, often under his Georges Teperino guise. His friend and recurring musical partner Roger Roger typically issued zany electronics under the name Cecil Leuter. This story is typical among the legions of composers.

I feel the high point of library music vitality was from roughly 1968-1982, though the amount of decent 80’s libraries is scarce. Further into the 80’s the music got increasingly tacky, especially on the British labels Bruton, de Wolfe and KPM, mixing rock elements with fusion and disco, resulting in many failed ideas that neverless ended up gracing many television programs and radio themes.

These are pretty broad statements meant to clue some folks in to library music as a whole, though on the fringes there were numerous small labels who only issued a few albums, and even still, some labels are only noteworthy through rumor, having become so scarce as to not being tracked down at all. Many of these labels produced some very challenging and often avant garde music, some venturing more into the modern interpretive dance music, and less a commercial venture. I’m sure there are so many thousands of stories hidden within those recording studios, television and radio stations, etc… with hundreds of faceless, seemingly selfless composers pushing out the goods to little or no fanfare. Some of these composers were relatively famous through other means and did libraries for a little extra cash (many tracks did in fact became famous themes for TV, radio and film). For some of these composers, it was their sole creative and financial venture, but it’s safe to say that now for many younger people who’ve discovered them anew, they are like rock stars.

Much of this music is a goldmine for sample hungry beatheads looking for “breakz.” I tend to approach it differently. Sure, I love a good solid groover, but I also look for something more cerebral, conceptual, or just plain different, to go deeper than just funky instrumental music.

Picking just several favorites was a difficult task. The ten titles below were chosen to showcase a variety of composers, labels and styles. A quick Google search of a composer or favorite title will quickly put you on your own path of discovery.

1. Sven Libaek Solar Flares (Peer/UK, 1974). One of my favorites! A very solid collection of groovy orchestral pop, but with that Libek twist: lots of dreamy vibes, clever, hooky arrangements, subtle wah-guitar, sneaky Moog, strong brass work, etc… Many fantastic tunes here, with a slight futuristic bent, but more in line with hazy summer days circa 1975.

1. Sven Libaek Solar Flares (Peer/UK, 1974). One of my favorites! A very solid collection of groovy orchestral pop, but with that Libek twist: lots of dreamy vibes, clever, hooky arrangements, subtle wah-guitar, sneaky Moog, strong brass work, etc… Many fantastic tunes here, with a slight futuristic bent, but more in line with hazy summer days circa 1975.

2. Oronzo de Filippi Meccanizzazione (Leo/Italy, 1969). A stunning library album featuring a strange mix of Morricone harpsichord phrasings, Jobim esque bossanova lounge, and some shifty Dave Brubeck tempos, with little bits of weird sounds thrown in. All in all it’s very sunny, hypnotic stuff. Deserves to be recognized as a solid latin jazz album. There’s a strong resemblance to Dots… era Stereolab in parts, regarding the jazzy latin rhythms and instrumentation.

2. Oronzo de Filippi Meccanizzazione (Leo/Italy, 1969). A stunning library album featuring a strange mix of Morricone harpsichord phrasings, Jobim esque bossanova lounge, and some shifty Dave Brubeck tempos, with little bits of weird sounds thrown in. All in all it’s very sunny, hypnotic stuff. Deserves to be recognized as a solid latin jazz album. There’s a strong resemblance to Dots… era Stereolab in parts, regarding the jazzy latin rhythms and instrumentation.

3. Serge Bulot Les légendes de Brocéliande (Sonimage/France, 1981). Moody and atmospheric, this is a very strong album – veering from ambient synth and folksy acoustic guitars to subtle violin arrangements; all set against a dreamy, swirling early 80’s post-punk haze that’s actually quite effective, recalling at once a sort of Factory records Durutti Column/Virginia Ashley type collaboration with some very slight ambient prog tendencies from the late 70’s. Bulot is a noted multi-instrumentalist with a vast, impressive collection of worldly instruments. From the looks of his myspace page he’s currently quite active composing and performing.

3. Serge Bulot Les légendes de Brocéliande (Sonimage/France, 1981). Moody and atmospheric, this is a very strong album – veering from ambient synth and folksy acoustic guitars to subtle violin arrangements; all set against a dreamy, swirling early 80’s post-punk haze that’s actually quite effective, recalling at once a sort of Factory records Durutti Column/Virginia Ashley type collaboration with some very slight ambient prog tendencies from the late 70’s. Bulot is a noted multi-instrumentalist with a vast, impressive collection of worldly instruments. From the looks of his myspace page he’s currently quite active composing and performing.

4. Francis Monkman Tempus Fugit (Bruton/UK, 1978). Phonkay space age fuzak! Here the keyboard wiz tears through stellar fantasy lifestyle music, with the terse focus of a falcon and the cheese merchant chops of Rick Wakeman’s little brother (?). Of course, this was on the British late 70’s standard jazz disco funk label Bruton. Here you’ll find plenty of Rhodes massaging, synth-swell galore, and hard clavinet stomping mood pieces that do little to deter your image of spacemen in tight red leather pants, headbands and elbow length white gloves. Run (don’t walk) away slowly.

4. Francis Monkman Tempus Fugit (Bruton/UK, 1978). Phonkay space age fuzak! Here the keyboard wiz tears through stellar fantasy lifestyle music, with the terse focus of a falcon and the cheese merchant chops of Rick Wakeman’s little brother (?). Of course, this was on the British late 70’s standard jazz disco funk label Bruton. Here you’ll find plenty of Rhodes massaging, synth-swell galore, and hard clavinet stomping mood pieces that do little to deter your image of spacemen in tight red leather pants, headbands and elbow length white gloves. Run (don’t walk) away slowly.

5. Nino Nardini & Roger Roger Jungle Obsession (Neuilly/France, 1972). Classic moogxotica, though the electronic element is very minimal. This album is a little over-hyped in my opinion, but it’s still a very solid effort. There’s absolutely no weirdo synth filler here (good news for all those weird synth album haters), but elegantly composed lounge jazz with a heavy exotic vibe, befitting the title, and some requisite animal sounds chirping and roaring here and there.

5. Nino Nardini & Roger Roger Jungle Obsession (Neuilly/France, 1972). Classic moogxotica, though the electronic element is very minimal. This album is a little over-hyped in my opinion, but it’s still a very solid effort. There’s absolutely no weirdo synth filler here (good news for all those weird synth album haters), but elegantly composed lounge jazz with a heavy exotic vibe, befitting the title, and some requisite animal sounds chirping and roaring here and there.

6. Armando Sciascia Sea Fantasy (Vedette/Italy, 1972). A stunning, fully formed album of sea themes from symphonic to light jazz. Beautiful orchestration, use of experimental electronics, and most of all there’s an elegant haze over everything.

6. Armando Sciascia Sea Fantasy (Vedette/Italy, 1972). A stunning, fully formed album of sea themes from symphonic to light jazz. Beautiful orchestration, use of experimental electronics, and most of all there’s an elegant haze over everything.

7. Jacques Siroul Midway (Montparnasse 2000/France, 1975) A damn good batch of Morricone-esque groovy instrumental pop, with a little Andre Popp and Serge Gainsbourg tossed in. The rhythm section is beefy and flawless, giving the whole “lounge” factor a total makeover. The harmonica (which I typically don’t care for) makes very frequent appearances on this album, though it is in a melancholic “Midnight Cowboy” vein, and not an annoying bluesy-folk one. There are a couple of corny piano pop concertos, but the zig zag moog and top notch compositions make this one very solid and unique overall. I like to call it “elevator prog”. Yes, I just made that up. This has reissue written all over it, from the crowd-pleasing heavy beats to the smart arrangements and generally great tunes. It’s quickly become one of my favorite albums!

7. Jacques Siroul Midway (Montparnasse 2000/France, 1975) A damn good batch of Morricone-esque groovy instrumental pop, with a little Andre Popp and Serge Gainsbourg tossed in. The rhythm section is beefy and flawless, giving the whole “lounge” factor a total makeover. The harmonica (which I typically don’t care for) makes very frequent appearances on this album, though it is in a melancholic “Midnight Cowboy” vein, and not an annoying bluesy-folk one. There are a couple of corny piano pop concertos, but the zig zag moog and top notch compositions make this one very solid and unique overall. I like to call it “elevator prog”. Yes, I just made that up. This has reissue written all over it, from the crowd-pleasing heavy beats to the smart arrangements and generally great tunes. It’s quickly become one of my favorite albums!

8. Stringtronics Mindbender (Peer-Southern/UK, 1972). This is something of a showcase effort from Barry Forgie, Anthony Mawer, Nino Nardini, and Roger Roger, each displaying their own brand of baroque jazz, with the emphasis on furiously sawed strings. [The first half of Mindbender is a 6-track suite composed by UK library legend Barry Forgie. Recorded in one 3-hour session, it’s a unique psych/funk/baroque exploration that’s made this LP the holy grail of library music collectors for years.]

8. Stringtronics Mindbender (Peer-Southern/UK, 1972). This is something of a showcase effort from Barry Forgie, Anthony Mawer, Nino Nardini, and Roger Roger, each displaying their own brand of baroque jazz, with the emphasis on furiously sawed strings. [The first half of Mindbender is a 6-track suite composed by UK library legend Barry Forgie. Recorded in one 3-hour session, it’s a unique psych/funk/baroque exploration that’s made this LP the holy grail of library music collectors for years.]

9. Joel Vandroogenbroeck Contemporary Pastoral and Ethnic Sounds (Coloursound/Germany, 1980) Ah, what a beaut’! Joel Vandroogenbroeck (aka: VDB Joel) was the main, only consistent member in Brainticket, and on this album he blends the requisite flute with synths and exotica tinged percussion, and comes up with a winner, an almost pop/mainstream approximation of the exotica-library variety. Surely this era of his work is probably lumped in with the new-age crowd (if it is lumped in anywhere at all!), but don’t let such things deter you from a wonderful listen. Majestic peaks of sound wash around, with an Echoplexed flute zipping all over the spectrum. I’m reminded of some long lost Herzog film, as the pastoral post-hippie vibe here bodes well with mid-period Popol Vuh, though in a slightly more synthetic way. There’s even a funky track with sample worthy “breaks” and some nasty clavinet; a seemingly out-of-place track, but it works well. For the most part, Vandroogenbroeck brings an old school krautrock/prog sensibility to the proceedings. Highly recommended!

9. Joel Vandroogenbroeck Contemporary Pastoral and Ethnic Sounds (Coloursound/Germany, 1980) Ah, what a beaut’! Joel Vandroogenbroeck (aka: VDB Joel) was the main, only consistent member in Brainticket, and on this album he blends the requisite flute with synths and exotica tinged percussion, and comes up with a winner, an almost pop/mainstream approximation of the exotica-library variety. Surely this era of his work is probably lumped in with the new-age crowd (if it is lumped in anywhere at all!), but don’t let such things deter you from a wonderful listen. Majestic peaks of sound wash around, with an Echoplexed flute zipping all over the spectrum. I’m reminded of some long lost Herzog film, as the pastoral post-hippie vibe here bodes well with mid-period Popol Vuh, though in a slightly more synthetic way. There’s even a funky track with sample worthy “breaks” and some nasty clavinet; a seemingly out-of-place track, but it works well. For the most part, Vandroogenbroeck brings an old school krautrock/prog sensibility to the proceedings. Highly recommended!

10. Various Artists Under Water Vol. 2: Under and Over the Water Surface (Sonoton/Germany, 1978). Absolutely stunning! This is a top notch collection of spooky yet elegant jazz played with beautiful unease. The woodwinds soar alongside the harps, plucky bass, water logged tubas and trombones, and the brief synth vignettes all add up to a great flow. Fans of moody modal jazz would find much to love here. It’s not too out-there like many conceptual libraries, and is a wonderful, darker cousin to Sven Libaek’s stellar Ron & Val Taylor’s Inner Space, though perhaps a bit more cerebral. It fits into the underwater-as-outer space metaphor quite well – both dark places of mysterious power, stifling vulnerability, and utter loneliness. Standout album track for me is “Wet Suit”. Side one is the mostly jazz section, composed by the duo of Sam Sklair and Oscar Sieben (with one short track by J. Fox & M. Prindy), while side two consists of moody electronic ambience courtesy of Mladen Franko. Very highly recommended!

10. Various Artists Under Water Vol. 2: Under and Over the Water Surface (Sonoton/Germany, 1978). Absolutely stunning! This is a top notch collection of spooky yet elegant jazz played with beautiful unease. The woodwinds soar alongside the harps, plucky bass, water logged tubas and trombones, and the brief synth vignettes all add up to a great flow. Fans of moody modal jazz would find much to love here. It’s not too out-there like many conceptual libraries, and is a wonderful, darker cousin to Sven Libaek’s stellar Ron & Val Taylor’s Inner Space, though perhaps a bit more cerebral. It fits into the underwater-as-outer space metaphor quite well – both dark places of mysterious power, stifling vulnerability, and utter loneliness. Standout album track for me is “Wet Suit”. Side one is the mostly jazz section, composed by the duo of Sam Sklair and Oscar Sieben (with one short track by J. Fox & M. Prindy), while side two consists of moody electronic ambience courtesy of Mladen Franko. Very highly recommended!

For further listening: A few more of my favorites worth tracking down are Walt Rockman’s space-age fairy-tale lullaby, Biology (Sonoton/Germany, 1978), Simon Park’s prog-ish Electric Bird (de Wolfe/UK, 1974), Romolo Grano’s Musica elettronica 1 (Joker/Italy, 1973) featuring superb, scary ambience and bleep-bloop blast, the disturbingly dark Egisto Macchi Voix (Gemelli/Italy, 1970), and the certified classic Cops, Crooks and Spies featuring some moody crime jazz cues by Eddie Warner.

View my complete list of over 350 library records here. —Norm

Do you have a favorite Sound Library composer or title? Share them in the comments field below:

Iron Maiden “The Number of the Beast” (1982)

This is Heavy Metal before the genre had all of the Rock & Roll stripped away from it. Because it still has those roots, the album is refreshingly soulful and full of rich textures. Not to worry, though, it’s still plenty fast and heavy. “Invaders” crawls under your skin and sticks with you longer than the written-to-be-catchy chorus of the album’s big hit, “Run for the Hills.” Said hit is also a stellar track, however, as is the haunting “Children of the Damned.” Not to put too fine a point on it, but “Number of the Beast” rules! If you think that Iron Maiden is hokey, dated or “Satanic,” and you haven’t actually taken to time to listen to their work, then you are doing yourself a great disservice. Don’t confuse this classic with the throwaway nostalgia that was released by scores of imitators a few years later. Intricate, pounding, powerful and creative – if those are words that describe good music to you, then look no further than “Number of the Beast.” –Lucas

This is Heavy Metal before the genre had all of the Rock & Roll stripped away from it. Because it still has those roots, the album is refreshingly soulful and full of rich textures. Not to worry, though, it’s still plenty fast and heavy. “Invaders” crawls under your skin and sticks with you longer than the written-to-be-catchy chorus of the album’s big hit, “Run for the Hills.” Said hit is also a stellar track, however, as is the haunting “Children of the Damned.” Not to put too fine a point on it, but “Number of the Beast” rules! If you think that Iron Maiden is hokey, dated or “Satanic,” and you haven’t actually taken to time to listen to their work, then you are doing yourself a great disservice. Don’t confuse this classic with the throwaway nostalgia that was released by scores of imitators a few years later. Intricate, pounding, powerful and creative – if those are words that describe good music to you, then look no further than “Number of the Beast.” –Lucas

Mike Holt “Dreamies” (1974)

In 1972 Bill Holt quit his suit job and descended into his basement with an acoustic guitar, a synthesizer and other electronic equipment, and a 4-track, and created this completely unique and hauntingly beautiful album.

The songs are 2 long sound collages sort of like “Revolution #9” by the Beatles, from which he drew inspiration (they are entitled ‘Program 10’ and ‘Program 11′, obviously to be seen as continuations of the Beatles’ ‘Revolution #9’. But Holt’s songs sounds different from that, in that they are structured around meditative and simple innocent poetic verses and chords strummed on the acoustic. The effect of this mixed with soundbites from radio and television from the 1960’s, and household noises, and electronic noises, is to create a unified whole where all the sounds of life mix together, all the registers and filters that we use to process the barrage of information that we receive, get torn down, and it all mixes together with Holt’s childlike, slightly disturbing verses to create a semi-Freudian mix. The songs are made interesting by Holt’s lovingly built songs, in which he spliced together what must have been hundreds of pieces of tape by hand, and where glass breaking, popcorn popping, snippets of Beatles songs, radio broadcasts of Cassius Clay fights, and Kennedy speeches mix together.

I only hope that the story I have told makes it sound as interesting as this album is. I know that the sound collage method is a sort of independent music strain of its own, and I must admit that this is my only real dabbling in it. But other sound collage material is less easy to listen to than this. The songs are long (25 minutes or so each) but the sensibility with the acoustic guitar is not as restricted as other sound collage pieces, this one is a man reaching out with the breadth of his wonderful ideas to create a beautiful, honest, frightening trip. —Mike

Os Mutantes “A Divina Comedia Ou Ando Desligado” (1970)

Mutantes reached their apex with the release of “A Divina Comedia Ou Ando Desligado” which translates to A Divine Comedy or I walk Disconnected. This is a flawless record. Rita Lee is at the top of her game when she sings “Meu refrigeradora noa funciona” (my refrigerator doesn’t function). The track which precedes it, “Desculpe, baby” (I’m sorry baby) is one of the most sexy and beautiful songs ever sung. It reminds me of Wong Kar-Wai’s movies (he made Chungking Express and Happy Together). These are incredible pop tunes, but they (as some of the other reviews show) aren’t for everyone. Os Mutantes emerged from the Tropicalia movement of 60’s Brazil. If you enjoy this cd you may want to check out other tropicalist’s: Gilberto Gil, Caetono Veloso, Gal Costa, Tom Ze, Maria Bethania. Jorge Ben is not considered tropicalia, but he is very incredible and sang a song on the first Os Mutantes album. Mutantes have more of a western flavor than some of the contemporaries. If you like them more for the apparent influence of the beatles and the rolling stones, you may want to check out the Peruvian band, We All Together.

This album is essential stock for a healthy record collection, its like eating broccoli! —fossilfrolic

Stomu Yamash’ta “Freedom Is Frightening” (1973)

Japanese percussionist/composer Stomu Yamash’ta settled in England in 1972, after studying music in his native country and later in the USA. He worked mainly as a composer for theatre music, but his signing as a recording artist for the Island label brought his work to the attention of a wider audience, which later led to him forming the group East Wind, which recorded this exceptional album. Combining forces with some of the best British musicians at the time, the band included Yamash’ta on drums and percussion, his wife Hisako on violin, guitarist Gary Boyle (Isotope), keyboardist Brian Gascoigne, and bassist Hugh Hopper (Soft Machine). The music is a wonderful fusion of Western and Far Eastern elements as well as many cross genre excursions, from atmospheric ambient to high spirited Jazz-Rock Fusion. Although Yamash’ta became mostly known for the “Go” recordings featuring Traffic’s Steve Winwood, a few years later, this is truly his most remarkable album recorded for Island and the one that withstands the test of time most adamantly. Wholeheartedly recommended! —Adam

John Martyn “Solid Air” (1973)

Solid Air is an amazingly effective amalgamation of blues, folk, and jazz. Though I can’t think of any album that sounds similar musically, Solid Air reminds me of Astral Weeks because it creates an emotion that is entirely its own. The title track drew me in; Martyn uses his voice like an instrument so it melts into the saxophone part, creating a totally unique sound. The album continued to be a mesmerizing listening experience and it shows off Martyn’s handle of a wide variety of musical styles. “Over The Hill” and “May You Never” are folk masterpieces, the former highlighted by Richard Thompson’s fabulous mandolin performance and the latter with its unforgettable melody. “I’d Rather Be The Devil” and “Dreams By The Sea” are both exciting, menacing tracks that show off Martyn’s skills on electric guitar with his impressive command of the Echoplex guitar effect. The former builds in tension and then crashes down into a peaceful musical section that ends the song on a serene note. The latter recreates some of the jazzy atmosphere of the title track with another fantastic saxophone part. “Don’t Want To Know,” “Go Down Easy” and “Man In The Station” are mellow but engaging folk tracks where the combination of Martyn’s voice and the tinkling instrumental parts are quite soothing. “The Easy Blues” shows Martyn’s strengths as an acoustic blues performer and the album closes on an uplifting, peaceful note with “Gentle Blues.” The album is so consistent, it is impossible for me to pick favorites. It simply deserves five stars. —Nathan

Bruce Palmer “The Cycle is Complete” (1971)

Bruce Palmer came to (brief) fame as one fifth of Buffalo Springfield, from which his frequent deportations often negatively affected the group’s touring schedule. Prior to this he reached almost-fame in The Mynah Birds, which also included Rick “Super Freak” James and fellow Canadian Neil Young. Following his return to Canada in 1968, Palmer began playing locally in Toronto again, and eventually he was offered a record deal with Verve, the result of which is The Cycle Is Complete. Sounding like early Krautrock efforts in a similar vein to Tangerine Dream and Can, the album is nonetheless structured far more loosely than it’s German cousins. It will quite likely come as a total surprise to fans of Buffalo Springfield, even if they’ve enjoyed the band’s occasional branching out into Psychedelia. —Anajondas

This obscure solo release by one-time Buffalo Springfield bassist, Bruce Palmer is one of my all-time favorite records. The album features free-flowing, trippy jazz-rock in the vein of Can “Future Days” or David Axelrod’s “Song of Innocence.” Neither of these comparisons really do it justice though as this LP is utterly unique and truly defies genre. It also possesses a mysterious charm and reveals itself slowly and begs repeated listening. Palmer passed away in ’04 but the spirit and magic of this album will always remain for those of us lucky enough to discover it. —David

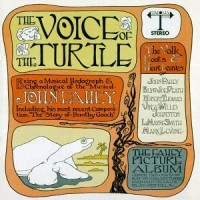

John Fahey “The Voice of the Turtle” (1968)

Like some of John Fahey’s other projects in the ’60s, this was actually recorded and assembled over a few years, and primarily composed of duets with various other artists (including overdubs with his own pseudonym, “Blind Joe Death”). One of his more obscure early efforts, Voice of the Turtle is both able and wildly eclectic, going from scratchy emulations of early blues 78s and country fiddle tunes to haunting guitar-flute combinations and eerie ragas. “A Raga Called Pat, Part III” and “Part IV” is a particularly ambitious piece, its disquieting swooping slide and brief bits of electronic white noise reverb veering into experimental psychedelia. Most of this is pretty traditional and acoustic in tone, however, though it has the undercurrent of dark, uneasy tension that gives much of Fahey’s ’60s material its intriguing combination of meditation and restlessness. —Richie Ubermench

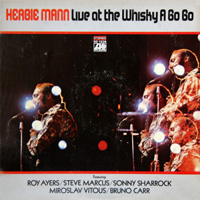

Herbie Mann “Live at the Whisky A Go Go” (1969)

Oh my Lordie is this record a slab of righteous funky soul jazz. With Roy Ayers and Sonny Sharrock in the lineup, how can you go wrong? Although they had been with Herbie for a while by now in variations of this lineup, this record is quite a few shades funkier than earlier efforts like Windows Opened. It’s comprised of only two long tracks on each side, with crisp engineering and production by the Atlantic team of Bill Halverson and Sr. Ertegun. The first tune is a mid-tempo sizzler, electric bass from Miroslav Vitous locking in nicely with drummer Bruno Carr, and some understated percussion work from Herbie when he’s not riffing on flute. There’s plenty of room for all the soloists to stretch out on this one, although Sharrock restrains himself to chugging along in a loose but tasty two-chord rhythm part. He lets loose his free-jazz guitar on the next track, however — the upbeat ‘Philly Dog,’ a tune written by Rufus Thomas and famously recorded by the Mar-Kays a few years earlier. Their version tops out around 3 minutes; this one stretches out about ten minutes longer than that. While Sonny Sharrock’s own work over the next few decades is undoubtedly more challenging and avant-garde than anything he recorded with Herbie Mann, I have to say I really, really enjoy his bursts of madness over the organic and tuneful funk grooves of the records they made together, when he comes blasting in like a furnace. Roy Ayers is, well, Roy Ayers, and makes the addition of anyone on keys to this live setting completely unnecessary. I tend to feel that Herbie Mann has been underappreciated in general – written-off by jazz purists early in his career as a sell-out, and often passed over by crate diggers in search of more obscure beats. He was definitely on a roll in 1969, with the amazing Memphis Underground LP also coming out that year. —flabbergasted