Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake is a work of pure genius, from the title of the album, through the seemingly mish-mash blend of rock, psychedelia, music-hall and ridiculous fairy tale back to the music of the title track. Side one knits together some classic rock songs, my favourites being “Afterglow” (which manages to give me goose bumps) and “Song Of A Baker” (as close to a pastoral song as East End boys are going to get) – two great rock songs, with the instrumental title track, psychedelia and music-hall (“Rene”). All good pieces. An unlikely mix, but they pull it off. The genius is that they manage to mirror this strange mix of styles on side two, while incorporating it into a fairy tale told part in song and part in gobbledegook by a narrator. And it works well (contrast the artistically less successful Beach Boys’ fairy tale EP Mt. Vernon And Fairway). It works because they don’t take themselves too seriously. A masterpiece! –Jim

Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake is a work of pure genius, from the title of the album, through the seemingly mish-mash blend of rock, psychedelia, music-hall and ridiculous fairy tale back to the music of the title track. Side one knits together some classic rock songs, my favourites being “Afterglow” (which manages to give me goose bumps) and “Song Of A Baker” (as close to a pastoral song as East End boys are going to get) – two great rock songs, with the instrumental title track, psychedelia and music-hall (“Rene”). All good pieces. An unlikely mix, but they pull it off. The genius is that they manage to mirror this strange mix of styles on side two, while incorporating it into a fairy tale told part in song and part in gobbledegook by a narrator. And it works well (contrast the artistically less successful Beach Boys’ fairy tale EP Mt. Vernon And Fairway). It works because they don’t take themselves too seriously. A masterpiece! –Jim

Psych and Prog

Premiata Forneria Marconi “The World Became the World” (1974)

The World Became The World opens with a prehistoric monster in the 10 minute apocalyptic epic “The Mountain”, a chilling choral intro giving way to the menace of the main riff before proceeding to explore PFM’s penchant for constant development and change over the course of a song. The fact that the vocals (sung from the point of view of a mountain on a dying planet) are sung in English through a thick Italian accent, and have been mixed low and soaked in reverb, makes them nearly unintelligible, yet it only serves to heighten the otherworldly tension. The vibe of this song sets the template for this album – toning down the wide scope of their earlier work, with tracks that feature more repetition and have a foggy sonic character, notably featuring a fair amount of coarse mellotron chords. “The Mountain”‘s shadow looms over the delicate ballad “Just Look Away”, and the title track, which closes the first side recalling early King Crimson in it’s marriage of soft passages with a doomy, mellotron infused chorus. Side two opens with a bang, again, in the form of “Four Holes in the Ground” and follow up track “Is My Face on Straight”, two intense, rhythmically complex, yet occasionally playful tracks that keep moving in new directions throughout their duration. Great stuff. A bass solo opens the instrumental “Have Your Cake and Beat It”, a track that wanders around in jazz fusion territory before out of nowhere, a huge cathedral organ emerges, with a beautiful, simple guitar melody on top closing out the album on a grand scale. —Ben

Captain Beyond “Captain Beyond” (1972)

Psychedelic rock emerging from its Technicolor cocoon as a decidedly more metallic butterfly. This is one of the first metal albums and still one of the best. It runs through a quick half hour of seriously kick-ass riffs and tricky rhythms that would suffice to leave some of us sufficiently breathless were it not also for the stoner imagery and a general atmosphere of stoopid awesomeness that I find transporting—despite myself. Sure, it gets overly dopey towards the end, but most of its listeners are doped up by that point, anyway. Guitar, bass, and drums manna for those of us who like that sort of thing. As for the rest of you… well, who asked you, anyway? Highly recommended late-night listening. –Ben

Psychedelic rock emerging from its Technicolor cocoon as a decidedly more metallic butterfly. This is one of the first metal albums and still one of the best. It runs through a quick half hour of seriously kick-ass riffs and tricky rhythms that would suffice to leave some of us sufficiently breathless were it not also for the stoner imagery and a general atmosphere of stoopid awesomeness that I find transporting—despite myself. Sure, it gets overly dopey towards the end, but most of its listeners are doped up by that point, anyway. Guitar, bass, and drums manna for those of us who like that sort of thing. As for the rest of you… well, who asked you, anyway? Highly recommended late-night listening. –Ben

Roky Erickson and the Aliens “The Evil One” (1981)

After serving some time in a mental institution, Roky Erickson, gifted vocalist of the prolific psych outfit 13th Floor Elevators, pheonixed into a paranoid messiah of rock, shedding any traces of campiness from his 60’s catalog in the proccess. “The Evil One” is a raging slab of psychedelic punk driven by Roky’s wonderful Texas fried and acid fed voice. He shrieks in terror as if to warn world of the demons in his mind. Although the lyrical subject matter is almost comical; vampires, a two headed dog, the devil, etc…, it’s delivered with a sincerity comparable to Syd Barrett’s solo albums or even a homeless person in the street raving on about something out to get them. But aside from any side stories of mental breakdown or heavy drug intake, the record is a cold cut ripper. Full speed 70’s hard rock with out any filler or forced attitude and killer guitar runs throughout. A must have for rock, punk, or psychellic heads. Just make sure your mind is together before dropping the needle, it might not come back. -Alex

After serving some time in a mental institution, Roky Erickson, gifted vocalist of the prolific psych outfit 13th Floor Elevators, pheonixed into a paranoid messiah of rock, shedding any traces of campiness from his 60’s catalog in the proccess. “The Evil One” is a raging slab of psychedelic punk driven by Roky’s wonderful Texas fried and acid fed voice. He shrieks in terror as if to warn world of the demons in his mind. Although the lyrical subject matter is almost comical; vampires, a two headed dog, the devil, etc…, it’s delivered with a sincerity comparable to Syd Barrett’s solo albums or even a homeless person in the street raving on about something out to get them. But aside from any side stories of mental breakdown or heavy drug intake, the record is a cold cut ripper. Full speed 70’s hard rock with out any filler or forced attitude and killer guitar runs throughout. A must have for rock, punk, or psychellic heads. Just make sure your mind is together before dropping the needle, it might not come back. -Alex

Sergio Mendes & Brasil ’66 “Stillness” (1971)

This is not one of your parent’s radio-friendly Brasil ’66 LP’s (although we love those too). Here the group seamlessly blend folk, Brazilian pop and psychedelic rock for some surprising results. The often sampled, funky version of Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth” is a definite highlight along with the quiet title track, the jazzy version of Joni Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning,” Caetano Veloso’s “Lost in Paradise” and the breath-taking arrangement of Blood, Sweat and Tears’ “Sometimes in Winter.” This often overlooked LP is a Jive Time Records’ staff favorite and one that sees a lot of our turntable. It’s also relatively scarce for a Sergio Mendes title so grab it when you see it! -David

This is not one of your parent’s radio-friendly Brasil ’66 LP’s (although we love those too). Here the group seamlessly blend folk, Brazilian pop and psychedelic rock for some surprising results. The often sampled, funky version of Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth” is a definite highlight along with the quiet title track, the jazzy version of Joni Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning,” Caetano Veloso’s “Lost in Paradise” and the breath-taking arrangement of Blood, Sweat and Tears’ “Sometimes in Winter.” This often overlooked LP is a Jive Time Records’ staff favorite and one that sees a lot of our turntable. It’s also relatively scarce for a Sergio Mendes title so grab it when you see it! -David

Dead Wrong: A Non-Deadhead’s Guide

to the Grateful Dead’s Studio Albums

There are very few bands as polarizing as the Grateful Dead, but even their most rabid fans and harshest detractors can agree on one point: The band personified a type of relationship a band can have with its audience. It’s now a model that many bands — especially those of the “jam band” variety — emulate and strive for, and one that is almost taken for granted in today’s fragmented music-consumer culture. It’s easy to forget just how pervasive the Deadhead phenomenon was, especially when it peaked during the final years of the Dead’s active existence. But all parties must come to an end, and when the Grateful Dead (wisely) decided to call it quits after Jerry Garcia’s sad but unsurprising death in 1995, the coliseum and stadium parking lots emptied out, and many Deadheads moved on.

Looking back on this era, it’s clear now that the Dead’s cultural impact often eclipsed their actual music. But as the shows become fading memories for those who experienced them and as a new generation of listeners discover the Grateful Dead, the focus is returning to the band’s rich musical history — where it belongs. Often brilliant, usually at least interesting, and only rarely unlistenable, the Grateful Dead weren’t afraid to take chances, and they adapted to changing times and environments while compromising very little for either. It’s a well-worn cliche that the Dead’s strength was as a live-performance unit. Indeed, a hardcore Deadhead can likely recite the set-list, verbatim, from the second set of a 1987 Alpine Valley show, but if you ask him if the original “Fire on the Mountain” is on Terrapin Station or Shakedown Street, you’re likely to be met with a blank stare.

In many ways, this preference for the live Dead is warranted, but it’s not always justified. The Dead’s natural habitat was onstage, for sure, but even during their best years (late ’60s and early ’70s), their exploratory jams did not always take flight, and they could be sloppy and meandering just as easily as they could be virtuosic and transcendental. Sometimes the controlled environment of the recording studio helped the Dead reign in some of their more excessive tendencies and focus their creative energies into making more cohesive musical statements. The end results of these endeavors varied widely in quality, especially during their later years. And there is certainly no avoiding the fact that the band suffered a critical blow in 1972 with the loss of lead vocalist/organist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, who brought and took with him an irreplaceable rawness and blues authenticity. Still, most of the Dead’s studio output from all stages of their storied career is at least worth a listen. And now, revisiting their catalog, it’s clear that some of it can even be called essential. So here, for newcomers to the band (or old-timers wishing to explore the more neglected areas of their work), is a short list of some of the Dead’s more notable attempts at conquering the studio LP format, warts and all.

1. Anthem of the Sun (1967) Many fans of ’60s garage rock (this writer included) love the Dead’s raw and hyperactive debut LP (read our review), but devotees of hardcore 60’s psych will take to this follow-up even more. Melding snippets of live performances to effects-heavy studio-recorded material, the band weaves a sonic tapestry that is at once puzzling and mystical. While some slow bits occasionally threaten to bog things down, this early artistic triumph shows the studio Dead at their most adventurous.

1. Anthem of the Sun (1967) Many fans of ’60s garage rock (this writer included) love the Dead’s raw and hyperactive debut LP (read our review), but devotees of hardcore 60’s psych will take to this follow-up even more. Melding snippets of live performances to effects-heavy studio-recorded material, the band weaves a sonic tapestry that is at once puzzling and mystical. While some slow bits occasionally threaten to bog things down, this early artistic triumph shows the studio Dead at their most adventurous.

2. Aoxomoxoa (1969) Originally to be titled, “Earthquake Country”, this is the Dead’s most atmospheric record. Folksy, quiet, and dark, its songs are subtle and sometimes don’t even seem like songs at all, more like stream-of-consciousness sound poems. On shaky ground with the rest of the band during the recording sessions, Pigpen and Bob Weir’s presence is minimal, making this mostly Garcia’s show. Still, his creaky vocals, coupled with Robert Hunter’s surrealistic lyrics, make for a record that is wonderfully creepy and bizarre.

2. Aoxomoxoa (1969) Originally to be titled, “Earthquake Country”, this is the Dead’s most atmospheric record. Folksy, quiet, and dark, its songs are subtle and sometimes don’t even seem like songs at all, more like stream-of-consciousness sound poems. On shaky ground with the rest of the band during the recording sessions, Pigpen and Bob Weir’s presence is minimal, making this mostly Garcia’s show. Still, his creaky vocals, coupled with Robert Hunter’s surrealistic lyrics, make for a record that is wonderfully creepy and bizarre.

3. Workingman’s Dead (1970) This is the first release in a pair of career and genre-defining country rock albums. For many, its follow-up, American Beauty, is the best studio album the Dead ever recorded. But most of these folks would agree that Workingman’s Dead comes in a very close second. Possessing a slightly grittier sound than the more polished American Beauty, every track here is a winner. Some of the band’s most popular songs such as “Uncle John’s Band” and “Casey Jones” are here, but it’s the less overplayed tracks that make it one of the greats. Among these fine moments are “New Speedway Boogie”, a commentary on the fateful Altamont music festival (where the band shared billing with the Rolling Stones) and “Easy Wind,” a showcase for Pigpen, who seizes the opportunity to make the most soulful five minutes to be heard on any Grateful Dead studio album.

3. Workingman’s Dead (1970) This is the first release in a pair of career and genre-defining country rock albums. For many, its follow-up, American Beauty, is the best studio album the Dead ever recorded. But most of these folks would agree that Workingman’s Dead comes in a very close second. Possessing a slightly grittier sound than the more polished American Beauty, every track here is a winner. Some of the band’s most popular songs such as “Uncle John’s Band” and “Casey Jones” are here, but it’s the less overplayed tracks that make it one of the greats. Among these fine moments are “New Speedway Boogie”, a commentary on the fateful Altamont music festival (where the band shared billing with the Rolling Stones) and “Easy Wind,” a showcase for Pigpen, who seizes the opportunity to make the most soulful five minutes to be heard on any Grateful Dead studio album.

4. Blues for Allah (1975) The Dead released three studio albums on their short-lived record label in the mid-70s: Wake of the Flood, From the Mars Hotel, and this one. All entries in this “Grateful Dead Records Trilogy” show the band’s growing jazz and fusion influences, and Blues for Allah represents the culmination of this productive experimentation. The Dead had been on hiatus a year before the LP’s recording sessions began, and this seems to have done them a world of good. Pigpen is long gone at this point, but keyboardist Keith Godcheaux is on fire and contributes some of the best work he’s done since joining the band. (And thankfully, the presence of his wife/backing-vocalist, the much maligned Donna, is kept to a minimum.) Featuring the “Help on the Way-Slipknot-Franklin’s Tower” song cycle, a live staple for the rest of the Dead’s career, this is the closest the Dead ever came to bottling their onstage lightning.

4. Blues for Allah (1975) The Dead released three studio albums on their short-lived record label in the mid-70s: Wake of the Flood, From the Mars Hotel, and this one. All entries in this “Grateful Dead Records Trilogy” show the band’s growing jazz and fusion influences, and Blues for Allah represents the culmination of this productive experimentation. The Dead had been on hiatus a year before the LP’s recording sessions began, and this seems to have done them a world of good. Pigpen is long gone at this point, but keyboardist Keith Godcheaux is on fire and contributes some of the best work he’s done since joining the band. (And thankfully, the presence of his wife/backing-vocalist, the much maligned Donna, is kept to a minimum.) Featuring the “Help on the Way-Slipknot-Franklin’s Tower” song cycle, a live staple for the rest of the Dead’s career, this is the closest the Dead ever came to bottling their onstage lightning.

5. Terrapin Station (1977) In the late ’70s, the Dead signed with Arista Records, and the label would release the remainder of the band’s studio output during the band’s active existence. Many of these records are riddled with half-baked ideas, unsuccessful attempts at then in-vogue musical styles, and dated production values. Terrapin Station is certainly not immune to these pitfalls, but there’s something very interesting about watching a band, one who for many years avoided the usual machinations of the music industry, try to reinvent themselves as an FM-friendly arena rock act. Even more interesting is the fact that here the Dead sometimes threaten to pull this off! Though dated and overproduced, Terrapin Station is probably the band’s strongest later studio effort, and it still retains a certain charm. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about the two records that came after it, Shakedown Street and Go to Heaven.

5. Terrapin Station (1977) In the late ’70s, the Dead signed with Arista Records, and the label would release the remainder of the band’s studio output during the band’s active existence. Many of these records are riddled with half-baked ideas, unsuccessful attempts at then in-vogue musical styles, and dated production values. Terrapin Station is certainly not immune to these pitfalls, but there’s something very interesting about watching a band, one who for many years avoided the usual machinations of the music industry, try to reinvent themselves as an FM-friendly arena rock act. Even more interesting is the fact that here the Dead sometimes threaten to pull this off! Though dated and overproduced, Terrapin Station is probably the band’s strongest later studio effort, and it still retains a certain charm. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about the two records that came after it, Shakedown Street and Go to Heaven.

Further listening: Ironically, the Dead had their biggest commercial success with 1987’s In the Dark, long after their creative peak. Though its hit single, “Touch of Grey”, made the band more popular than ever, many early adopters despised the album. To be fair, it did represent a return to form as far as songwriting was concerned, but its production values keep it eternally trapped in the ’80s. If you must hear the Dead’s studio work of this era, it might be worth a listen. But a better route to take is one that stops by the many wonderful solo efforts of the Dead’s individual members. Jerry Garcia’s first LP, 1972’s Garcia (read our review), easily holds its own alongside the Dead’s best work. Percussionist Mickey Hart also recorded some great stuff, and his first album, Rolling Thunder, featuring a star-studded lineup of musicians and vocalists, is a must hear! —Richard P

Did we leave out your favorite Grateful Dead or Dead-related solo LP? We’d love to hear your comments:

Hawkwind “Space Ritual” (1973)

Rock made interstellar matter. A blessed stars collision makes possible this weird, antisocial record. A quite rancid and demodé spot that doesn’t resemble anything done before or after. A crash between the cave-like distortion and the outer space, mystic sounds. A search for God based on primitive rites. Pagans worshipping Nature, Fire, Elements, Cosmos. Ancient divinities, entities such as Sun Ra or Blue Cheer. A true astral projection, an initiation turn down to the depths of the Earth and up to the confines of the Universe. Excessive, saturated, vehement, foul and whimsical. At the antipodes of simplicity. And yet, it sounds basic and direct. A gloomy journey towards light. Guitars buried deep down in the mix, foregrounded bass and vocals and some occasional trumpets sounding like distant low-frequency signals. I’ve never found anything like this. An artificial album. A touched-up live which is a pure celebration of experience. It’s both YES and NO. An endless curl. –Laranra

Rock made interstellar matter. A blessed stars collision makes possible this weird, antisocial record. A quite rancid and demodé spot that doesn’t resemble anything done before or after. A crash between the cave-like distortion and the outer space, mystic sounds. A search for God based on primitive rites. Pagans worshipping Nature, Fire, Elements, Cosmos. Ancient divinities, entities such as Sun Ra or Blue Cheer. A true astral projection, an initiation turn down to the depths of the Earth and up to the confines of the Universe. Excessive, saturated, vehement, foul and whimsical. At the antipodes of simplicity. And yet, it sounds basic and direct. A gloomy journey towards light. Guitars buried deep down in the mix, foregrounded bass and vocals and some occasional trumpets sounding like distant low-frequency signals. I’ve never found anything like this. An artificial album. A touched-up live which is a pure celebration of experience. It’s both YES and NO. An endless curl. –Laranra

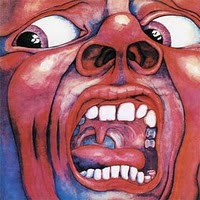

King Crimson “In the Court of the Crimson King” (1969)

Released in progressive rock’s ground zero year of 1969, King Crimson’s debut instantly upped the ante in terms of expanding the possibilities of where rock music could go, it’s expansive songs and the individual members’ mastery of their instruments defining the genre. One seriously heavy and hyper-intelligent statement, In the Court of the Crimson King explodes with the primal, scalding venom of “21st Century Schizoid Man,” as lyricist Peter Sinfield’s Vietnam-era imagery of “innocents raped by napalm fire” delivered through Greg Lake’s distorted vocals are encircled by a torrent of lacerating Fripp guitar chords, tightly controlled high-octane ensemble passages, and free-jazz discord from Ian McDonald’s layered sax solo. “21st Century Schizoid Man” sets you up for an almost reverse-whiplash effect, as tracks like the exploratory “Moonchild” and lush chamber balladry of “I Talk to the Wind” widen the scope further with their fragility, while the stately “Epitaph” and bombastic title track are carried on the towering waves of a booming, primitive/modern mellotron orchestra, as images of doom and destruction abound. In the Court of the Crimson King would set the template for much of King Crimson’s work, despite the band’s multiple lineup changes, with it’s ability to bludgeon, soothe, and strike a nerve throughout this landmark release resulting in a distinguished rock institution. –Ben

Released in progressive rock’s ground zero year of 1969, King Crimson’s debut instantly upped the ante in terms of expanding the possibilities of where rock music could go, it’s expansive songs and the individual members’ mastery of their instruments defining the genre. One seriously heavy and hyper-intelligent statement, In the Court of the Crimson King explodes with the primal, scalding venom of “21st Century Schizoid Man,” as lyricist Peter Sinfield’s Vietnam-era imagery of “innocents raped by napalm fire” delivered through Greg Lake’s distorted vocals are encircled by a torrent of lacerating Fripp guitar chords, tightly controlled high-octane ensemble passages, and free-jazz discord from Ian McDonald’s layered sax solo. “21st Century Schizoid Man” sets you up for an almost reverse-whiplash effect, as tracks like the exploratory “Moonchild” and lush chamber balladry of “I Talk to the Wind” widen the scope further with their fragility, while the stately “Epitaph” and bombastic title track are carried on the towering waves of a booming, primitive/modern mellotron orchestra, as images of doom and destruction abound. In the Court of the Crimson King would set the template for much of King Crimson’s work, despite the band’s multiple lineup changes, with it’s ability to bludgeon, soothe, and strike a nerve throughout this landmark release resulting in a distinguished rock institution. –Ben

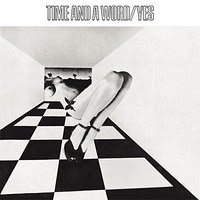

Yes “Time and a Word” (1970)

1970s Time And A Word is one of the greatest first-generation Progressive Rock albums, and a wonderful musical snapshot of a young and unsettled Yes that hadn’t quite yet settled into their later Prog Godhood role. Only two-thirds of the “classic” Yes lineup is here, Jon Anderson at Frotman, and the wondrous Chris Squire at Bass and Bill Bruford at Drums. Otherwise it’s part-time Yes man Tony Kaye on Keyboards and Yes’s original (And quite substandard compared to Steve Howe) Guitarist Peter Banks. Still Time And A Word is a wonderful solid album with some truly amazing songs hidden in it’s grooves. The title track is, in my opinion, the most gorgeously beautiful song Yes ever created. And No Opportunity Necessary No Experience Needed is simply thrilling. If you are a fan of Yes, or Progressive Rock you need Time And A Word. –Karl

1970s Time And A Word is one of the greatest first-generation Progressive Rock albums, and a wonderful musical snapshot of a young and unsettled Yes that hadn’t quite yet settled into their later Prog Godhood role. Only two-thirds of the “classic” Yes lineup is here, Jon Anderson at Frotman, and the wondrous Chris Squire at Bass and Bill Bruford at Drums. Otherwise it’s part-time Yes man Tony Kaye on Keyboards and Yes’s original (And quite substandard compared to Steve Howe) Guitarist Peter Banks. Still Time And A Word is a wonderful solid album with some truly amazing songs hidden in it’s grooves. The title track is, in my opinion, the most gorgeously beautiful song Yes ever created. And No Opportunity Necessary No Experience Needed is simply thrilling. If you are a fan of Yes, or Progressive Rock you need Time And A Word. –Karl

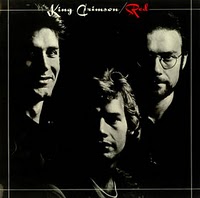

King Crimson “Red” (1974)

A caged beast of a record, and easily this group’s best, it strips away most of their obscurantist pretensions to serve up a guitar bass and drum assault that runs frequently into the red and is something to behold: Bruford’s drumming is jaw-dropping, while Fripp plays with a dark metallic intensity that suggests he’s one of rock’s wasted talents. I can even put up with John Wetton here, whose ferocious bass playing is more like a second (maybe third) lead instrument and whose singing has a kind of macho bravura that suits this music’s seething intensity. Still, the beast is caged. I’m always a little let down by the second side, which is what keeps Red from essentially essential status, with the wandering “Providence” (another crack at the improv-based excursions heard on the previous album) and the somewhat undercooked “Starless.” No, I’m not kidding: “Starless,” which many listeners seem to think is a masterpiece, could’ve used a little more work. I’m forever disappointed by the whole trajectory of this track, which at 12-some minutes would’ve benefited from a few more (the majestic ending should’ve been lengthier, to provide a kind of bookend equivalent to the sturm-und-drang of “Red;” it may be quibbling, but it’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to). So, instead of the Godzilla of prog-rock tracks, “Starless” is merely a woolly mammoth. This group never made the great record they should’ve made. This one’s the only one that comes close. And oh so close. –Will

A caged beast of a record, and easily this group’s best, it strips away most of their obscurantist pretensions to serve up a guitar bass and drum assault that runs frequently into the red and is something to behold: Bruford’s drumming is jaw-dropping, while Fripp plays with a dark metallic intensity that suggests he’s one of rock’s wasted talents. I can even put up with John Wetton here, whose ferocious bass playing is more like a second (maybe third) lead instrument and whose singing has a kind of macho bravura that suits this music’s seething intensity. Still, the beast is caged. I’m always a little let down by the second side, which is what keeps Red from essentially essential status, with the wandering “Providence” (another crack at the improv-based excursions heard on the previous album) and the somewhat undercooked “Starless.” No, I’m not kidding: “Starless,” which many listeners seem to think is a masterpiece, could’ve used a little more work. I’m forever disappointed by the whole trajectory of this track, which at 12-some minutes would’ve benefited from a few more (the majestic ending should’ve been lengthier, to provide a kind of bookend equivalent to the sturm-und-drang of “Red;” it may be quibbling, but it’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to). So, instead of the Godzilla of prog-rock tracks, “Starless” is merely a woolly mammoth. This group never made the great record they should’ve made. This one’s the only one that comes close. And oh so close. –Will

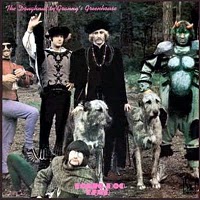

The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band “The Doughnut in Granny’s Greenhouse” (1968)

The great lost psychedelic album. On their second album the Bonzos knock off the trad jazz parodies and pair their surreal lyrics and wild imaginations with rock music to match. Neil Innes still gets to sing the catchiest songs — “Beautiful Zelda”, for instance, examines the perils of dating a space alien — but Vivian Stanshall beats him with what could be the band’s mission statement, “My Pink Half Of The Drainpipe”. Plus there’s the amazing Love parody “We Are Normal” (“and we dig Bert Weedon!”). The summit, though, is the too awesome for words “Rhinocratic Oaths”, which, with its cheery narration (“You should get out more, Percy, or you’ll start acting like a dog, ha ha … He was later arrested near a lamp-post”) reveals the Bonzo’s ultimate truth: that there is nothing so lunatic as what passes for everyday life. (Hey, that Dada/Doo-Dah wasn’t in their name for nothing.) If you have any spark of imagination or individuality, you must get this record. –Brad

The great lost psychedelic album. On their second album the Bonzos knock off the trad jazz parodies and pair their surreal lyrics and wild imaginations with rock music to match. Neil Innes still gets to sing the catchiest songs — “Beautiful Zelda”, for instance, examines the perils of dating a space alien — but Vivian Stanshall beats him with what could be the band’s mission statement, “My Pink Half Of The Drainpipe”. Plus there’s the amazing Love parody “We Are Normal” (“and we dig Bert Weedon!”). The summit, though, is the too awesome for words “Rhinocratic Oaths”, which, with its cheery narration (“You should get out more, Percy, or you’ll start acting like a dog, ha ha … He was later arrested near a lamp-post”) reveals the Bonzo’s ultimate truth: that there is nothing so lunatic as what passes for everyday life. (Hey, that Dada/Doo-Dah wasn’t in their name for nothing.) If you have any spark of imagination or individuality, you must get this record. –Brad

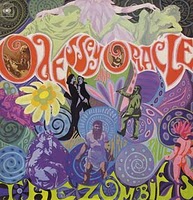

The Zombies “Odessey and Oracle” (1968)

If elegantly arranged chamber pop going for baroque is your cup of tea, get out your best china. Just about every minute of this record is beautifully constructed and rich in mood, and the arrangements are continuously compelling: comparisons with other groups don’t suffice, because this is a record on its own terms. The Zombies were kind of a musician’s group; all very good players writing very conscientiously for accessibility and sophistication (rather like those Beatles blokes, but I wasn’t gonna compare). Even if this disc falls off a bit on the second half, which isn’t wall-to-wall classic, the vocal harmonies and the variety of musical textures these guys manage to wring out of every chord should satisfy, even when the song isn’t quite spot-on. But jeepers, when they’re on, they are really on. One of the high water marks of ’60s pop. –Will

If elegantly arranged chamber pop going for baroque is your cup of tea, get out your best china. Just about every minute of this record is beautifully constructed and rich in mood, and the arrangements are continuously compelling: comparisons with other groups don’t suffice, because this is a record on its own terms. The Zombies were kind of a musician’s group; all very good players writing very conscientiously for accessibility and sophistication (rather like those Beatles blokes, but I wasn’t gonna compare). Even if this disc falls off a bit on the second half, which isn’t wall-to-wall classic, the vocal harmonies and the variety of musical textures these guys manage to wring out of every chord should satisfy, even when the song isn’t quite spot-on. But jeepers, when they’re on, they are really on. One of the high water marks of ’60s pop. –Will