While mourning the recent death of Moody Blues bassist/vocalist John Lodge (RIP!), I realized that we’ve not reviewed any albums by his elegant and quite popular British psych-rock group. A very puzzling state of affairs, to be sure. So, time to remedy that oversight.

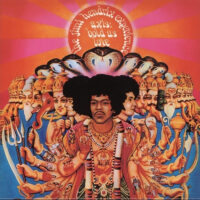

In Search Of The Lost Chord was the second of a fantastic, six-album run by the Moody Blues that spanned from 1967 to 1971. The commercial success of 1967’s Days Of Future Passed paved the way for the band to enjoy unfettered creative freedom in the studio for Lost Chord. Inspired by Timothy Leary’s lysergic proselytizing and other cultural sources of mind expansion (including Sgt. Pepper’s), the Moodies added flutes, sitar, tablas, autoharp, harpsichord, and cellos to their standard rock instrumentation. And all five members got to flex their compositional muscles. The result is one of the zeniths of major-label psychedelia.

Drummer Graeme Edge’s brief “Departure” prepares you for something momentous, as an ever-rising chord leads spectacularly into the soaring romp of freedom that is Lodge’s “Ride My See Saw.” Although it was a bit late, the song exemplifies that liberating, Summer Of Love spirit and it definitively proved that the Moody Blues could rock. (No surprise that it was covered by NYC rockers Bongwater in 1987.) Flautist/saxophonist Ray Thomas’ “Dr. Livingstone, I Presume” brings whimsical orchestral pop that positively explodes with ebullience in the chorus (“We’re all looking for someone”). Thomas rises to the occasion again on “Legend Of A Mind,” a glorious tribute to notorious trip-trip-maker Tim Leary. This is superbly arranged big-budget psychedelia with absolutely riveting Mellotron and flute passages. A real tour de force, it’s the Moodies’ “A Day In The Life.”

Mellotron manipulator Mike Pinder comes correct with “The Best Way To Travel,” a brilliant specimen of late-’60s UK psych, which, historians agree, is some of the most elaborate and sublime psych. Plus, Pinder sings a bit like Ringo Starr. On Justin Hayward and Thomas’ “Visions Of Paradise,” a gorgeous, circuitous flute intro leads into Days Of Future Passed-style baroqueness, with sitar embellishments. Things get unbearably poignant on Hayward’s “The Actor,” a well-crafted psych ballad with heavenly ambitions. Edge’s cosmic poem, “The Word,” segues into Pinder’s sitar- and tabla-spiced psych gem “Om,” which is enhanced by transportive vocal harmonies. Sure, it’s a period piece, like In Search Of The Lost Chord itself, but, man, what a period. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.