A singles collection, issued in 1996 compiling many of this British bands tough to find 45’s.

A singles collection, issued in 1996 compiling many of this British bands tough to find 45’s.

Founded in ’92, this band took “shoegaze” and bought it to such an extreme that you were no longer looking at your shoes in bliss, you were staring clean through your shoes, through the floor, through warm soil, into the molten/frozen core of the Earth. Sheet after sheet after sheet after blanket after pillow of feedback, with the most beautiful, elegantly sung/whispered vocals I have ever heard in my life. Every track swells, crests and recedes in a seemingly endless haze of soft white glows. When I was first exposed to this band in high school, the extremity of the basement production quality, coupled with my ear searching for debris to hang onto as the onslaught of noise cascaded out was comparable to the first times I heard Napalm Death’s “Scum” or the brutal intensity of Siege. The power of these recordings is unparalleled. I have owned this record for over 10 years, and with each listen, I detect a swirling, massive beehive texture, stinging and surging that I missed last time around. And the time before. Since those high school days, I have heard this band under the influence of more drugs than I care to mention in a work related review, but I will say this: They re-create the feeling of tripping more than ANY group from the 60’s I am aware of. Now will someone sell me a copy of their s/t LP sometimes called ‘Rural Psychedelia’ that I still cannot track down a copy of? –Richard

Rock

Pink Fairies “Kings of Oblivion” (1973)

If you are curious about inspired Motorhead’s unique sound, and have already explored MC5, The Stooges, Hawkwind and The Groundhogs, then go no further than this album. Larry Wallis and Duncan Sanderson later appeared on Motorhead recordings and the song “City Kids”, debuting here, is also featured on Motorhead’s 1979 LP On Parole. “City Kids” here is more stark than Lemmy’s amphetamine-enriched version, but no less powerful. ‘I wish I was a Girl” is a track worthy of the Groundhogs “Split” album in its inventiveness – but the raw power is undiminished. Sure it lacks a little something due to recording techniques in those days – a clear sense of perspective is needed, as this is music of its time and yet way ahead of it. “When’s the Fun Begin” is not one to listen to if you’re verging on a depression, but provides a nice contrast to the driving “Chromium Plating” and “Raceway.” Something about these tracks actually seems to contain the acrid smell and excitement of motor racing in a far less clinical way than say, Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain.” “Chambermaid” is quirky and may require several listens to pick up on the humour, and “Street Urchin” is the track that leaves you wanting more.

Kings of Oblivion is one of the best-kept secrets of hard rock – and an important part of its history. If you like your rock and roll “real,” it doesn’t get much more real than this. Just don’t go expecting Judas Priest, AC/DC or Black Sabbath; This is high-energy rock that truly belongs on the streets, and a landmark album in its genre. Truly a classic. —Fuuhq

Golden Earring “Moontan” (1973)

This 1973 outing is the album that raised Golden Earring to an international level of popularity, primarily on the strength of the hit single and enduring radio favorite “Radar Love.” However, there is much more to this album than just that hit.

It starts with a bang thanks to “Candy’s Going Bad,” a piece that starts off as a thunderous, pounding rocker but transforms midway into a bluesy instrumental mood piece. Other highlights include the hit single “Radar Love,” a relentless rock tune with a left-field instrumental break in which tribal drums duel with a big band-style horn section, and “Just Like Vince Taylor,” a guitar-slinging slice of boogie rock that pays tribute to the fallen rock idol of the title. The album also includes what may be the group’s finest prog effort in “Vanilla Queen”: this classic builds from pulsating, ominous verses dominated by synthesizer into a hard-rocking chorus and also throws in a stark acoustic guitar midsection before climaxing in a frantic band jam augmented by blaring horns and an ever-spiraling string section. Despite the album’s overall strength, not every song reaches these heights: “Are You Receiving Me?” recycles some hooks from the group’s past classic “She Flies on Strange Wings,” and the twangy country-pop of “Suzy Lunacy (Mental Rock)” is a little too poppy to gel with the rest of the album. However, even these tunes benefit from tight arrangements and a spirited, totally committed performance from the group.

The result is an album that retains its power today. In the end, Moontan is a necessity for Golden Earring fans, and a worthwhile listen for anyone interested in 1970s rock at its most adventurous. —Donald

The Rolling Stones “Sticky Fingers” (1971)

The first album released by the Stones in the 1970s, it’s an album drenched in a sheen of perspiration. Many of the tracks were conceived in the late 60s (Wild Horses, Brown Sugar) and as such, would fit right in on the previous Stones’ album, Let It Bleed. While that album oozed menace, this album seems to be mired in a drug-induced haze. Known for its hits, the real gems are hidden like a junkie’s last healthy vein.

The album kicks off with Brown Sugar, a song about interracial sex and cheap dope. A classic, it captures the initial surge of energy that propels the Stones into the 70s. Bobby Keys’s sax adds an extra touch of raunchy sex appeal. “Sway” is a yearning tune full of resignation to an inevitable descent into depression. “Wild Horses” is cut from the same thematic cloth though it is far more famous. “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” is a seven minute-plus song, a showcase for MIck Taylor’s virtuoso guitar. Keith Richards has stated that Ron Wood is his favorite co-guitarist but Taylor is the better musician. The majority of the song is a jam between dueling guitars, two brothers of diverse personalities trying to outdo each other in front of the audience. “You Gotta Move” is a nod to the blues masters the Stones revered (and from whom they pinched a tune or two… or three… or…). “Bitch” opens Side B. It’s pace is quicker than Brown Sugar but while a good tune it lacks that extra bit of edge and bite that the album opener has. “I Got the Blues” is a retreat back into that dark cave of weariness. The lyrics express hope that one’s former flame is now happy but Jagger’s voice betrays this as a lie; he misses her and what he would do do have her back. “Sister Morphine” is the bottom of the drug induced state; the singer’s waiting for Death. “Dead Flowers” is the hidden jewel of this album. The lyrics reveal shame, an attempt to run from the light that would reveal the singer’s addiction. Hidden from daylight, from prying eyes of the upper crust of society, one can indulge in that blissful euphoria that the drug of choice provides. There’s a promise that the singer will outlive others and will be sure to be at their graves long after they’re gone. As melancholy as “Moonlight MIle” is, there’s a glimmer of hope in it. The lyrics indicate an partial emergence from the haze and at least offer the possibility that things will be better, if not then, than someday.

This is the Stones album you play when you’re hanging on your back porch with your one or two friends or your lover, a beer or a glass of wine in your hand; the one you play as you drive down dark lonely roads as you travel through middle America; the one makes your pause and think about that girl that got away when you hear it in a pub on Thursday evening. It’s the one that lets you know that you’ve crawled through a mile of sewage and came out on the other side; dirty, sweaty, smelly, scarred. But alive. —Neunzehn

Squeeze “Cool for Cats” (1979)

Squeeze’s first three albums trace the startling transformation of a band evolving from a diamond-in-the-rough punk band with an unmistakable pop sensibility, to a polished new-wave outfit that seems to effortlessly crank out an unending stream of catchy masterpieces. “Cool For Cats” is the second album, and the sound is squarely in the middle between the stumbling debut, “UK Squeeze”, and the fully-developed third album, “Argybargy”, a true classic of Beatlesque pop-rock. The distinctive vocal sound of early Squeeze comes from the unusual gimmick of having both Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford singing the lead together, with Tilbrook an octave higher than Difford. But it wasn’t long before they moved away from that sound, with the sweeter-voiced Tilbrook gradually taking over most of the lead vocal chores from the courser Difford. At the same time, the punk-ish energy of the earlier material gave way to the slower tempos and polished professionalism that has characterized the band for most of their long career. This evolution was dramatic and unmistakable from the debut, to “Cool For Cats”, to “Argybargy”, by which time the transformation was almost complete. “Cool For Cats” highlights are many, starting with the lead track, “Slap And Tickle”, which is very reminiscent of the debut. The album then hits a lull, with the next 5 tracks not making much of an impression, but it finishes with 6 straight winners, starting with the high-energy pop of “Hop Skip And Jump”. The next track is the stunning “Up The Junction”, with Difford’s lyrics telling a woeful tale of boy meets girl, boy gets girl, boy loses girl because of his heavy boozing. Practically a short story set to music. The booze theme is repeated 2 songs later on the irresistibly catchy “Slightly Drunk”. In fact, excessive drinking would become a recurring theme for lyricist Difford for many years to come. The next track, “Goodbye Girl” is a Tilbrook-sung ballad with a lovely melody, the type of song that would become Squeeze’s trademark. The album comes to a close with the delightful, punky title track. All in all, a stellar effort by one of the greatest pop-rock bands ever. —Eric

Camel “I Can See Your House From Here” (1979)

While prog-purists might frown at I Can See Your House From Here, which watches Camel trod closer to the middle of the road, anyone who’s been seduced by the easy-going charm that is the band’s calling card will find it well worth their time. Confusing lineup changes continue to hallmark the second phase of Camel’s career, which here features two keyboardists in Kit Watkins (Happy The Man) and Jan Schelhaas (Caravan), plus Colin Bass on his namesake and some lead vocals. Continuing to feel pressure from their label for some kind of chart action, Camel offer up straightforward pop-inclined material in the tense “Wait,” easy going melodies of “Your Love Is Stranger Than Mine,” and tough-guy tale “Neon Magic,” while “Remote Romance” is an odd stab at synth pop. Sandwiched between these tracks are the very Happy The Man-ish instrumental “Eye of the Storm,” and some excellent blends of prog and pop on “Who We Are” and “Hymn to Her,” before the cold vastness of space is explored via an extended guitar and synthesizer showcase in “Ice.” Despite it’s commercial leanings and continued shuffling of the band’s lineup, I Can See Your House From Here still delivers the Camel-essence. —Ben

Faces “First Step” (1970)

First Step establishes the revamped Faces’ change of direction with a set of woozy, laid back blues rock highlighted in swinging boogie numbers like “Shake, Shudder, Shiver,” “Three Button Hand Me Down” and the Delta flavored “Around the Plynth” (resurrected from Stewart and Wood’s tenure in The Jeff Beck Group), a stomping reading of Dylan’s “Wicked Messenger,” and the stately, powerful “Flying.” Elsewhere, the eminently affable Ronnie Lane checks in with a signature back country ballad in “Stone.” Fleshed out with two instrumentals, First Step ends up a little underwritten and jammy, but is ripe with the band’s signature brand of disheveled rock. —Ben

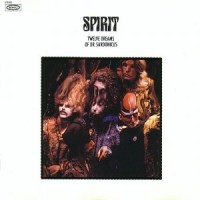

Spirit “Twelve Dreams of Dr Sardonicus” (1970)

Spirit was (and still is) sadly one of the most overlooked bands from the psychedelic era – perhaps it was the fact that the music was more akin to Soft Machine and other jazz-oriented bands of the day during the era when country/rock (the Dead, Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco, etc) began to dominate California rock… whatever the reason, Spirit deserves greater attention and praise than it has received.

While they DID score a surprise hit in 1968 with “I Got a Line on You,” it is without question the 1970 concept lp “The 12 Dreams of Dr.Sardonicus” that will forever define the band. The songs, like the talent in the band, are enormous and special, spanning the gamut from the jazzy blues of the wonderful “Mr. Skin” (tribute to drummer Cassidy) to the out and out psychedelia of the gorgeous “Love has Found a Way,” to the surrealism of “Animal Zoo.”

“12 Dreams” remains one of the most consistent listens that I own from late 60’s/early 70’s rock n roll. This is due most to the brilliant musicianship of Jay Ferguson, John Locke, Mark Andes, Ed Cassidy, and Randy California. The wonderful interplay between these men is top-rate, with California’s brilliance on the guitar meshing perfectly with stepfather Cassidy’s jazzy drumming (he was drummer for the Rising Sons, featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder). The songs, as I mentioned earlier, are brilliant and flow wonderfully. The combination of the two equals an album that I can’t put down for very long.

Fans of late 60’s rock know about Spirit. The time has come for the rest of the world to do the same. One of the most underrated and brilliant lps ever made. Period. —Steve

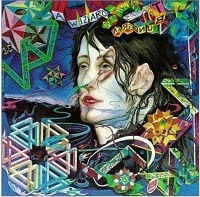

Todd Rundgren “A Wizard, A True Star” (1973)

Nothing could have prepared audiences in ’73 for the brain scrambler that is A Wizard, A True Star, a double-album’s worth of ideas crammed horizontally (in the brevity of the songs) and vertically (in the impenetrable layers of sound) onto one album, albeit a long one. Was this the same guy who released Something/Anything a year before? But start peeling A Wizard back, and that pop-rocker is still there, most notably on the impassioned “Sometimes I Don’t Know What to Feel,” space age soarer “International Feel,” oddly beautiful cabaret of “Zen Archer,” hard rock/lush pop hybrid “When The Shit Hits The Fan/Sunset Blvd.,” and the first of a new recurring theme for Todd, the uplifting anthemic “Just One Victory.” But the distinguishing characteristic of A Wizard is the 1 to 2 minute slices of “real” songs and outright weirdness that disorient the listener, to the point that a few tracks into this one you’ve either been totally seduced or completely given up, placing it as one of those polarizing efforts of either genius or bullshit, depending on your view. An easy five stars, of course. –Ben

Nothing could have prepared audiences in ’73 for the brain scrambler that is A Wizard, A True Star, a double-album’s worth of ideas crammed horizontally (in the brevity of the songs) and vertically (in the impenetrable layers of sound) onto one album, albeit a long one. Was this the same guy who released Something/Anything a year before? But start peeling A Wizard back, and that pop-rocker is still there, most notably on the impassioned “Sometimes I Don’t Know What to Feel,” space age soarer “International Feel,” oddly beautiful cabaret of “Zen Archer,” hard rock/lush pop hybrid “When The Shit Hits The Fan/Sunset Blvd.,” and the first of a new recurring theme for Todd, the uplifting anthemic “Just One Victory.” But the distinguishing characteristic of A Wizard is the 1 to 2 minute slices of “real” songs and outright weirdness that disorient the listener, to the point that a few tracks into this one you’ve either been totally seduced or completely given up, placing it as one of those polarizing efforts of either genius or bullshit, depending on your view. An easy five stars, of course. –Ben

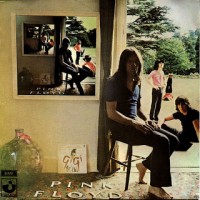

Pink Floyd “Ummagumma” (1969)

A double album of sustained unsettling bizarreness that manages to outdo most psychedelia by building it up in a live setting and tearing it down in the studio, this is arguably Pink Floyd at their rawest: one part live freak-out, one part studio freak-out. It prefigures much of what we’ve come to know and love by way of so-called krautrock: the incorporation of avant-garde forms into the rock format. Somebody had to do this sort of thing, no? And they get points for sheer nerve. Still, I’m not sure how many normal people can actually sit through this from start to finish. Listeners who appreciate avant-garde music will likely find this crude and boring, while people who cling to song-form and melody will likely find this alienating and boring. Let’s try to straddle the fence and hear this as a far-reaching rock record, which it is.

The live album is primo psychedelic freak-out stuff, with a rendition of “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” that surpasses the studio version by eight miles, and three other tracks from their first two albums: “Astronomy Domine” is more abstract than its Barrett incarnation and a refreshing variation that exposes its eerier side; while the two from A Saucerful of Secrets make up for the lack of intricate production flourishes by forging a new frontier in spaced-out noise. All four renditions are exceptional, and this is a classic live album, never mind the minor quibbles about sound quality.

The studio album is a little tougher to take, with four “suites,” each one contributed by one band member. It’s an impressive studio achievement and certainly a left-field rock experiment: psychedelic freak-out stuff with a more intellectual bent—meaning it’s not as interesting as the live album—though I’m sure it blew minds at the time of release. Richard Wright’s portion includes prepared piano and faux-free jazz and some moody mellotron parts complemented by chirping birds. It’s not bad. Roger Waters’ two contributions include a lengthy psych-folk ditty (with touches of Donovan) complemented by chirping birds and a babbling brook … and secondly a lengthy psych-folk rave-up that, as its title quite explicitly denotes, consists of nothing but human-simulated/studio-manipulated faux-rodent noises and an imitation of a drunken Scotsman. These are also not bad. David Gilmour’s piece is the most accessible, a suite that anticipates Meddle’s drifting atmosphere and even becomes songlike towards the end, with hints of King Crimson’s contemporaneous output. It’s probably the closest thing to the classic Floyd sound, and might appeal most to their rabid fans. Nick Mason’s percussion experiment is a kind of musique concrete for beginners, a mildly interesting tape-manipulated mood piece that wouldn’t be out of place as the soundtrack to some late-60s high school documentary about physics; it opens with a flute theme and slowly builds to a drum solo and then a multi-tracked drum duet before devolving back to its flute theme … it seems a little quaint nowadays but fits this lengthy record’s creepy vibe. And it’s not really bad, either.

All told, a much better album than it should be: a mindfuck for people who aren’t predisposed to having their minds frequently fucked, and definitely not among Floyd’s weakest releases…. Make of that what thou wilt. —Will

New Riders of the Purple Sage (1971)

New Riders of the Purple Sage is a strong debut, notable not only for the involvement of the legendary Jerry Garcia as pedal steel guitarist, but also for the great singing from John Dawson, the strong harmonies, David Nelson’s pickin’, and, perhaps most importantly, the catchy strong writing — there isn’t a weak song in the bunch.

Solidly in the county rock vein, this album is a whole different animal from Garcia’s work as a guitarist with the Grateful Dead or as a banjo player with Old and in the Way, so direct comparisons are difficult. Sure, the Dead played plenty of country material on American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, but this does not sound like either of those albums, nor does it evoke the Byrds’ brand of country rock; it’s more akin to the Stones’ “Dead Flowers” (with which, appropriately enough, the current lineup of NRPS has opened many shows since their debut in 2006). I have heard their style called cosmic country, which would seem to fit in reference to the “far out” pedal steel style of both of the band’s prominent pedal steel guitarists, so it seems as good of a label as any.

Those who enjoy the mournful qualities of Jerry Garcia’s voice probably will enjoy John “Marmaduke” Dawson’s lead vocals here, and a listener’s reaction to the lead-off track, “I Don’t Know You”, will probably serve as a pretty good indicator as to whether or not they will like the rest of the album. “I Don’t Know You” features some fun interaction between Garcia and Nelson, and any fears that these tunes will be stretched beyond the boundaries of good taste are allayed by its radio-friendly brevity of two-and-a-half minutes.

Those of us who happen to enjoy the Grateful Dead’s explorations only get one song substantially longer than five minutes on the entire album, so, again, although listeners may find some vocal, tonal, and instrumental common ground, this album does not sound like anything that the Grateful Dead have ever done. The one song where they do stretch out is the laid back “Dirty Business”, and we get to hear some raunchy pedal steel from Garcia there, just enough to satisfy my appetite for it. Other tunes, in particular “Henry”, “Louisiana Lady”, and “Glendale Train”, are such tight, fun singalongs that stretching them out with long jams would have seemed superfluous in this studio setting.

It’s great that Jerry hooked up with his longtime buddy David Nelson and the rest of the band to get this thing rolling with such a fine album, because, even after Jerry left this band to be replaced by the amazing Buddy Cage, the group played many great shows and recorded some strong tunes. I love this band, and, even with a slew of country rock and alt country bands cropping up over the years, to my awareness, none of them have ever really mined this same vein. —Len

Blue Öyster Cult “Tyranny and Mutation” (1973)

With considerably more vivid production and a greater focus on riff and rhythm than on atmosphere—and even more cryptic lyrics—the second BOC LP is superior to their debut by a dark country mile. The self-mythologizing continues, even picking up where the first record left off, with a revisitation of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police as some kind of secret Fascist society on the ferocious garage-burner “The Red & the Black.” The decadence and debauchery that threaded through their eponymous is in even stronger evidence here, too, with tracks such as the bluesy “O.D.’d on Life Itself” and the fiery proto-punk of “Hot Rails to Hell,” which anticipates bands like the Damned (albeit with the screwed-down-tight musicianship that make BOC’s early records such a treat and the contemporaneous live shows legendary). The album gets stranger as it progresses, with talk of Diz Busters, a Baby Ice Dog, and one of the band’s most bizarre creations, that Mistress of the Salmon Salt, who, moreover, is a Quicklime Girl. Zany might be the best word to describe the content here: they were often referred to as the “American Black Sabbath,” but the appellation only fits to the extent that BOC are similarly dark in their themes and can bring the Heavy when it’s called for: otherwise, these guys are punkier (Patti Smith was a close connection and occasional co-writer at the time), at once more traditionalist and more experimental (think the chug-chugging of the incipient Detroit punk scene crossed with the theatrical arrangements of Killer-era Alice Cooper and you’re on the right track), and a whole lot funnier than Birmingham’s doom purveyors. –Will

With considerably more vivid production and a greater focus on riff and rhythm than on atmosphere—and even more cryptic lyrics—the second BOC LP is superior to their debut by a dark country mile. The self-mythologizing continues, even picking up where the first record left off, with a revisitation of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police as some kind of secret Fascist society on the ferocious garage-burner “The Red & the Black.” The decadence and debauchery that threaded through their eponymous is in even stronger evidence here, too, with tracks such as the bluesy “O.D.’d on Life Itself” and the fiery proto-punk of “Hot Rails to Hell,” which anticipates bands like the Damned (albeit with the screwed-down-tight musicianship that make BOC’s early records such a treat and the contemporaneous live shows legendary). The album gets stranger as it progresses, with talk of Diz Busters, a Baby Ice Dog, and one of the band’s most bizarre creations, that Mistress of the Salmon Salt, who, moreover, is a Quicklime Girl. Zany might be the best word to describe the content here: they were often referred to as the “American Black Sabbath,” but the appellation only fits to the extent that BOC are similarly dark in their themes and can bring the Heavy when it’s called for: otherwise, these guys are punkier (Patti Smith was a close connection and occasional co-writer at the time), at once more traditionalist and more experimental (think the chug-chugging of the incipient Detroit punk scene crossed with the theatrical arrangements of Killer-era Alice Cooper and you’re on the right track), and a whole lot funnier than Birmingham’s doom purveyors. –Will