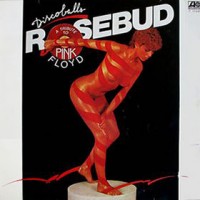

Being neither a massive fan of Pink Floyd OR Disco at the time I discovered Rosebud, you’d have been hard-pressed to convince me of this record’s genius based on description alone. But holy crap – this record goes beyond likes and dislikes, preferences and prejudices. Throw this sick puppy on the turntable once and JUST TRY to deny the power. I defy you to.

Like nearly all Disco success stories of the day, Rosebud was a studio project, strategically assembled from the cream of French session musicians of the era. The group lineup here is as impressive as it is confounding, featuring two members of the esteemed prog outfit, Magma, and a future Oscar and Grammy award winner in producer/arranger Gabriel Yared. Yared would go on to future triumphs with highly-acclaimed scores for “The English Patient,” “Cold Mountain,” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” but Discoballs made his name as a world-class producer/arranger, hinting at his bright future in composition.

A project like this could easily have slid down the treacherous slope into novelty, but the performances and arrangements are too combustible and visionary to dismiss. The dance floor incinerating transformation of “Have A Cigar” checks all of the boxes requisite for a disco track, while managing to sound fresh and exciting, building steadily to an ecstatic finale. The band play in such a tightly-coiled and controlled funk pocket that it almost sounds looped, and Yared’s subtle touches – hand claps on the breaks, cowbells dropping where the conga line would be, swooping string stabs – capitalize on the tension the band builds, whipping it into a frenzy of aural sensation by track’s end. All of this without the musicians ever breaking, or even varying from the initial vamp set up at the outset of the track. Even if there wasn’t an entire album of Floyd standards to ice the cake, “Have A Cigar” would be a legendary statement in and of itself. This is one of those tracks that feels like a total genesis moment – pointing the way forward to the House, Techno, and Electro movements of the ’80’s. I’d wager to guess there’d be no LCD Soundsystem without this record as well.

As my uncle always says whenever he hears this – “Man, when this song would play at Circus people would go crazy – dancing, fighting, pushing…” —YouTube comments for “Have A Cigar.” Nuff sed. —Jonathan Treneff