What is it about Reggae that inspires such polarized reactions? Scores of those who are otherwise musically well-versed and open-minded will register tangible expressions of apprehension when the irie sounds of Jamaica are mentioned. Reggae is a line in the sand for a lot of people, but I suspect that, as was the case for me, a lot of people have simply never had the right entry point – something beyond the ganja-huffing roommate who blasted Bob Marley’s “Legend” from dusk to dawn. Like the music of The Grateful Dead (read our guide), Reggae comes with a lot of baggage. Negative cultural associations abound, and the fact that at it’s root, it is a basically repetitive music sung in patois doesn’t exactly woo new listeners. Not to mention the sheer, daunting amount of recorded music out there.

In hopes of remedying this, we’ve put together a guide for the Reggae-wary. Contrary to simply being a list of “user-friendly” Reggae, these records all hopefully offer something slightly removed from the general expectations and stereotypes many of us have formed around Reggae music.

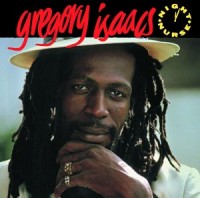

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae.

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae.

Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music.

Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music.

Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today.

Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today.

Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision.

Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision.

Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

Further listening: UK producer/musician/mover and shaker, Adrian Sherwood has been instrumental in breaking down the musical, social, and cultural barriers that have traditionally made Reggae such an insular concern. He founded the On-U Sound label in the ’80’s, initiating a flurry of releases by acts that pushed the core sounds and concerns of Reggae into new tributaries and uncharted territory. Singers & Players was a collective (featuring revered names in Reggae like Prince Far-I and Bim Sherman) who successfully cut the traditional Reggae template with eclectic flourishes and innovative production techniques influenced by Electronica and Industrial music. Dub Syndicate, meanwhile, serves as Sherwood’s love-letter to the Dubbing tradition. While remaining essentially modern and explorative, it’s also the most openly reverent concern of the On-U stable. In terms of pure aural experience, African Head Charge is easily the most experimental and out-there of the lot – and the furthest from traditional Reggae. The project of percussionist Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah, AFC is a serious next-level stew that incorporates elements of everything from nyabinghi, psychedelia, and the sampladelic nature of musique-concrete to create one of the most compelling listening experiences a curious ear could hope for. These groups are just a cursory dip into the deep well of talent nurtured by On-U Sound over the years, exploding Reggae’s one-dimensional stereotypes into a thousand new possibilities.

Like every genre, Reggae is a near-bottomless pit once you’ve taken the leap, full of enough curiosities and permutations to keep one busy for a couple of lifetimes. The aforementioned are only a fraction of potential entry points. If you’re willing to cast aside your assumptions and approach it with an open mind, you may find something you didn’t know you were looking for, and be pleasantly surprised by what you find. —Jon Treneff

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae.

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae. Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music.

Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music. Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today.

Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today. Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision.

Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision. Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.