Ask a Seattle music fan what were the great periods of Seattle music. Most would quickly name “Grunge” and The Seattle Sound of the late 80s until the mid-90s. (Pearl Jam, TAD, Soundgarden, etc.) Some would recall the first successful era I Seattle music-the days of the 50/60s teen-dances that spawned The Northwest Sound; The Wailers, The KIngsmen, Don and The Good Times, The Sonics, among others. To many there’s not much worthwhile in between The Northwest Sound and The Seattle Sound except for a smattering of arena acts like Heart, a handful of great psychedelic outfits, a few rock festivals or the inventive punk and post punk of bands like the U-Men, The Blackouts or Student Nurse.

Then ask the same fan to name the great black and African American artists the Northwest has produced. Inevitably the first name that will come up is Jimi Hendrix. Then maybe silence…a few folks might mention Ray Charles or Quincy Jones; but to be honest, Ray Charles was a Florida import biding his time in the Jackson Street clubs before chasing real fame elsewhere. Charles had been born in Albany Georgia, but spent most of his formative years in St. Augustine, Orlando, Jacksonville and Tampa…not Seattle.

Quincy Jones is an (almost) native son, having been born in Chicago, then moving to Bremerton at age 10, and finally to Seattle. Jones left Seattle at a fairly early age after time at Seattle’s famous Garfield High. It was here that Quincy Jones and Ray Charles first met. Neither would have imagined the mark they’d leave on American music. Jones reminisced in a 2005 PBS American Masters episode focusing on his career: “When I was 14 years old and Ray Charles was 16, our average night went like this: We played from seven to 10 at a real pristine Seattle tennis club, the white coats and ties, [playing] ‘A Roomful of Roses’ . . . From 10 to about one o’clock, we’d go play the black clubs: The Black and Tan, The Rocking Chair, and The Washington Educational and Social Club-which is a funny name, funkiest club in the world. We’d play for strippers and comedians and play all the Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and Roy Milton stuff, all that R&B. It was a vocal group. Then, at about 1:30 or 2 a.m., everybody got rid of their gigs and we went to the Elks Club to play hardcore bebop all night long . . .” Jones attended one semester at Seattle University, then onto The Berklee School of Music in Boston. By 1952 he was touring Europe playing trumpet with Lionel Hampton. He became a jazz composer, arranger, writer and player. This was years before his enormous recognition as one of the world’s premier record producers and well-respected music executive and philanthropist.

As for Jimi Hendrix, aside from being born in Seattle he also left quite young. The truth about Hendrix is that he does not really belong to Seattle. His success is rooted in his teen years in Seattle and his success in New York City and London, but he belongs to the world, (maybe even more) and continues to be a world-wide icon of the guitar and rock stardom. When he died there were as many tears shed in London, Paris or Rome as in his hometown.

Who does this leave? One could argue Sir-Mix-a-Lot, who, after all is said and done, had only one huge hit…but it’s a hit that has done well for himself and even today is part of the cultural consciousness. that went into more detail of the musicians and landscape of Seattle’s black community in the 60s and 70s.

The fact is that (mostly white, rock-oriented) writers and critics completely ignore the incredible history of Funk and Soul music that came out of Seattle from the mid-60s up ‘til the mid 70’s. This era stands up as well as any other musical movement Seattle has ever created..but few people will admit this. Even today “best of” lists mostly ignore black artists-or artists of any ethnicity other than white. Read any journalists’ or magazines top roster of Seattle bands. It’s unlikely to find any band that isn’t white…or at least maybe having a mixed-ethnicity member. Black music seems to be relegated to separate jazz, hip-hop or other genres not accepted as “mainstream”. It’s nice to see that this attitude has evolved for the betterover the past few decades., but there is still a dearth of coverage of Seattle’s ethnic music scene

That passing-over was partly rectified in 2004 when Light In The Attic Records released “Wheedle’s Groove: Seattle’s Finest In Funk & Soul 1965-75”. The album was a compilation of Northwest underground and long-forgotten singles written and performed by a group of sensational talent. When the album was released critics around the world took note and the album was almost universally acclaimed as a collection of long-lost masterpieces. It’s fair to say that the Seattle’s recorded funk and soul sounds only scratch the surface and is a genuine musical movement that should be looked at as a third great Seattle flourishing of creativity in spite of that. The discovery of Seattle’ thriving funk and soul era seems to have been spurred on by DJ Supreme La Rock.(real name Danny Clasevilla) an obsessive collector of esoteric and hard-to-find records.

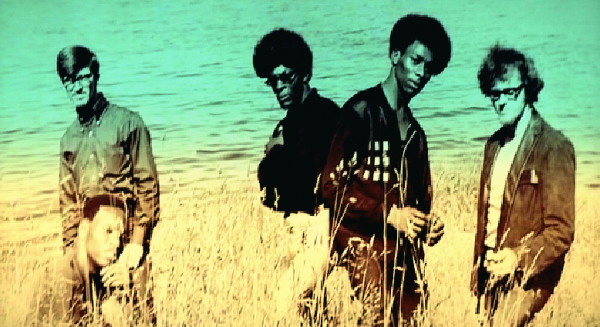

Closevilla says “I met with the owner of the Light in the Attic label (Matt Sullivan) for lunch one day and he asked me if I could re-release anything what would it be? I said all these Seattle funk 45s I have”. DJ Supreme had come across several Seattle singles in used-record bins by bands he’d never heard of. It was the beginning of a love-affair between him and the Seattle funk of the 60s and 70S. Clasevilla went on to curate the album “Wheedle’s Groove: Seattle’s Finest In Funk & Soul 1965-75” which was the first commercial release to highlight a mostly forgotten era of Seattle’s rich music history. The album caused such a great amount of interest that by 2009 a documentary film (by Jennifer Maas) explaining and re-visiting the rise and fall of Seattle funk. Members of the bands Cold, Bold & Together as well as The Black and White Affair are featured prominently. Former radio station KYAC owner and DJ Robert Nesbitt noted in the liner notes to the album;

“There was a minimum of twenty live-music clubs specializing in funk and soul, and all those joints jammed. There must have been twenty-five hard-giggin’, Superfly-like, wide-leg-polyester-pant-and-platform-shoes-wearing, wide-brim-hat-and-maxi-coat-sportin’, big-ass, highly-“sheened”-afro-stylin’, Kool & the Gang song-covering live bands playing four sets a night from 8 p.m. ‘til O-dark-thirty in the morning. And of course, the ladies were not to be outdone with their Pam Grier-Foxy Brown hoop earrings, mini-skirts and the ever- popular Afro Puffs. Each night, some band, somewhere, was kickin’ it. You could find Manuel Stanton of ‘Black and White Affair’ doing flips while playing bass on a Monday at the Gallery. Meanwhile, you might catch Robbie Hill, flashing like a Christmas tree in a red rhinestone-studded jumpsuit, matching red Big Apple cap and the huge hair, keeping the beat for his band Family Affair at the District Tavern. The Dave Lewis Trio, the highly stylized Overton Berry and the ultra-funky Johnny Lewis Quartet regularly played the Trojan Horse, while Cold, Bold & Together was house band at the legendary Golden Crown Up. Cookin’ Bag, with their heavy horn vibe was a major draw from Perls’ Ballroom in Bremerton to Soul Street”.

The album includes tracks by Patrinell Staten (aka Pastor Pat Wright), Ron Buford, Cookin’ Bag, Overton Berry and Cold, Bold and Together (featuring a very young man named Kenny Gorelick-now known as Kenny G.) All of these bands should have their names in the funk and soul firmament, but the world isn’t fair; especially in the case of the finest stand-out bands on the compilation; The Black and White Affair. All the artists-or the ones still remaining are also subjects of the film-each giving their account of their musical endeavors.

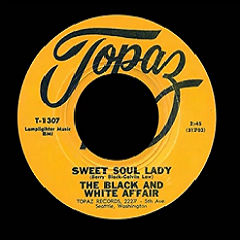

Three songs by The Black and White Affair are included “Wheedle’s Groove: Seattle’s Finest In Funk & Soul 1965-75”. which at the time were three of the four known surviving tapes. The songs themselves include the early funk single “Sweet Soul Lady”, and later “Bold Soul Sister, Bold Soul Brother”. Both singles brought them brief attention-but more importantly kept them working for years.

“Sweet Soul Lady” (backed with “Until The Real Thing Comes Along”) was engineered and recorded by the iconic Kearney Barton at his Audio Recording Inc. studio near downtown Seattle2227 Fifth Avenue2227 Fifth Avenue. The single was released on Topaz Records, a label founded in 1950s by John Hill and Rick Wheeldon. In 1961 Barton took possession of the label because of a debt owed him by Hill and Wheeldon. Barton began using the label as a cheap, efficient outlet for local bands to record and release small runs of 45’s. Practically no one with the fees to record was turned away. The one downside of Topaz Records was that since everything was done on the cheap there were no music promoters to “work” the singles to radio stations across the country. Consequently a single might do well in the Seattle regional market, but get absolutely no airplay in any other part of the country. Seattle had a tremendous amount of talent but as many writers and historians have pointed out, the weak link was there were no successful labels catering to the African American audience. No Stax (Memphis), no Motown (Detroit), no Chess Records (Chicago) to grab them up and give them first-class promotion and distribution. Most Funk and Soul artists from this era recorded and release very small runs of 7’ singles that very local record shops could stock, but most seem to have been sold out of the trunks of band members at their gigs. This is a DIY strategy that was common in the 1960s with all sorts of bands, and is still common among bands looking for wider audiences and to make back the cost of their records.

Quincey Jones’s brother, Lloyd, worked as an engineer at local radio station KYAC. KYAC was known as one of the few west coast radio stations that exclusively targeted the African American community during the mid- 60s. The station was practically the soul of Seattle’s black community, picking up interest from people of all ethnicities who enjoyed deep soul and funk as well as a way to keep up with local funk bands that KYAC always included in their playlists. It’s said that one day a DJ didn’t show up and the stations’ manager told Lloyd to fill-in for the missing disc jockey. Lloyd was out of his depth, but continued to progress as a DJ radio personality. It didn’t hurt his reputation that he was the younger brother of Quincy. It’s said he had sent his older brother a copy of “Sweet Soul Lady” after it became the station’s number one hit.

Although in 2009 Quincy Jones claimed he didn’t remember The Black and White Affair, they were, in fact, offered a contract by Jones’s label. Calvin Law, the de facto leader of The Black and White Affair, later joked that the band was so eager about the contract that they got to Los Angeles before the signed contracts arrived at the labell. Soon The Black and White Affair were playing Los Angeles clubs as prestigious such as The Factory, The Whisky, Gazzari’s, The Coconut Grove, The Daisy Chain, The Greek Theater, and Club Arthur. Their foray into the Hollywood music scene didn’t last long. They would find themselves back in Seattle because of “some conflicts”

Kearney Barton remembers their “conflicts” a bit differently than the band. “The Black on White Affair’s “Sweet Soul Lady,” was recorded and issued on Barton’s Topaz label.. When the song went #1 on KYAC, Barton contacted Scepter/Wand Records, about getting wider distribution. They showed interest. Barton told the band members the good news, but, they informed him they had already made a deal with Quincy Jones. Barton got suspicious when they asked him to call Jones, to seal the deal.

“I’d been friends with Quincy, done some work for him,” recalls Barton. “So I called and told him I had this record that was #1, and he said, ‘Hey, that sounds great. Send me a copy!'” But the minute Barton mentioned the artist, Jones’ disposition changed. “He said, ‘I don’t want to hear their name.'” Barton was stunned: “They told me they had a deal with you.”

“They did have a deal, until they started telling me how to run my label,” said Jones.

Barton tried again to get Scepter to pick up the band, but it was too late. The Black and White Affair would go on to record several more tracks with Barton and issue one more single in 1970 (“Bold Soul Sister. Bold Soul Brother” b/w “A Bunch of Changes”. Both are super-funky masterpieces – but once again the band was saddled by not having a label deal and ended up releasing them on Topaz and selling them locally. In a 2009 interview with Barton, he seems apologetic, but the fact is he was an engineer and a producer-not a front-line man for a major label. He had far too much work recording than to make calls on radio DJs and organizing marketing strategies. The Black and White Affair missed their boat. Eventually Sausage Records (France) would re-release the single, but since it’s an import it’s still hard to locate. Although the band had lost their chance at a national label they continued to be extremely popular with African-American audiences. In 2005 Pitchfork Magazine wrote of their recording “Bold Soul Sister Bold Soul Brother” (which is the opening track of the album “Wheedle’s Groove: Seattle’s Finest In Funk & Soul 1965-75”) and the documentary film based on it.

“One constant was Hammond C3 player and vocalist Calvin Law who you hear all over this track and who’s energy, powerful vocals, and his leading the band often with live impromtu arranging of the songs were a big part of the band’s electrifying sound. One can’t help but think of Ike and Tina’s different but similarly titled, more well-known… “Bold Soul Sister”. ( haven’t actually nailed down an exact date for BOWA’s track [1968]) and I gotta say from this track’s first opening machine gun snare hits, crunching drums, screeching organ and super tight and funky syncopated cymbal to the laid back swagger of the main guitar tag line and balls out soulful vocals”.

DJ Supreme also observed;

“The drums were crazy, and as the opening credits roll, we hear what he means: After a few ragged organ stabs, “Bold Soul Sister” goes into a clanging drums-only breakdown, hip-hop ore requiring only basic looping to become an instant rap song or b-boy soundtrack.

After their return to Seattle, The Black and White Affair continued to be a popular live act. In 2004, Tony Gable, a former member of Cold, Bold and Together told writer Kurt B. Reighley that the scene back then was more about enjoying the live performances, and showing off elaborate 60s and 70s soul outfits rather than anything getting out of hand.

“Violence wasn’t a problem, but racism was”says Tony Gable, a former member of Bold, Cold & Together, and a professional musician in the years since. “No matter how popular they became, African-American acts were unwelcome in particular venues. “There was a distinguishable degree of prejudice in the scene in the ’70s,” he recalls. “There were certain agencies that would not book you, certain clubs we could not play. One time, we went to play a club–I think it was an Elks Lodge, in the North End–and they thought we were just moving the equipment, and asked where the band was. And I said, ‘We are the band.’ And they wouldn’t let us perform.” Gable recalls how almost everyone in town was positive the Pacific Northwest would be the next hot spot. Not only were bands coming out of New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, but even Dayton, Ohio spawned big groups (Ohio Players, Zapp).

“A lot of us were expecting somebody to come discover us,” admits Gable. “For Quincy Jones to be sitting in the audience one night. That was one of the major mistakes we made. You pretty much had to leave, like Jimi Hendrix did, and go someplace else to get famous.” Although the bands didn’t “make it” Kearney Barton and other engineers had saved recorded tapes. The Black and White Affair’s two singles were found along with a surprisingly soulful version of “Auld Lang Syne” and a long-lost track called “Funky Manuel” celebrating Manuel Stanton’s accomplished, funky bass playing. The Black and White Affair spent years changing both drummers and names. The names ranged from The Black and White Affair to The Black on White Affair, and The Black on Black Affair. The last iteration of the band was “The Family Affair” which included Robbie Hill, the only remaining member of the band’s stream of drummer. “The Family Affair” also cut some great records, and had success as a touring band. The band’s name was appropriate since most of the members were actually related to Robbie Hill. All the other Black and White Affairs members had left the group because of money pressures, boredom, the simple desire to move on or alcohol.

So in the end what killed the Seattle funk scene and great bands like The Black and White Affair? The lack of radio play? Hard times? Not enough venues? To almost a single one of the musicians interviewed for the film “Wheedle’s Groove” the answer is one word: Disco.

Disco brought less trouble for owners, managers and bookers of clubs. It was cheaper to play recorded music. No hard to deal with band managers or drunk and high artists. To be sure audio, video and lighting equipment for disco have become wildly expensive. Especially for EDM shows; but back in those days patrons were often used to more mediocre sound systems and it wasn’t long before audio engineers upped their games. Then there’s the fact tha audiences not glued to the performance were more liable to spend more money at the bar.

The truth is that disco was a hard hit for many regional artists, while at the same time serving-up a thriving business for club owners. The best we can hope for-and what seems to have been delivered-is a love for the now-obscure artists, like The Black and White Affair, and a love of being incredibly overjoyed to hear the beats of something unknown from the past. There are plenty of undiscovered singles and bands out there. This is the lesson the great Seattle funk and soul bands have left us. It’s also the invaluable lesson DJ Supreme La Rock has given to the entire world. One person endlessly looking for rare records might end up unearthing an essential part of music history. Tenacity pays off whether it’s by an individual, a musician or a person with a dream.

– Dennis R. White. Sources; “Wheedle’s Groove; The AD Interview” (Aquarium Drunken, aquariumdrunkard.com/2011/05/16/wheedles-groove-the-ad-interview/retrieved Dec. 25, 2017); “Wheedles Groove” (Documentary film, directed by Jennifer Maas 2009); “Programming Aids” (Billboard Magazine, May 4, 1968); Russel Simins, Judah Bauer “Tracks From Van #9, The (The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Facebook, May 29, 2014); Andrew Matson ‘Thoughts on ‘Wheedle’s Groove,’ old-school Seattle soul/funk documentary at Seattle International Film Festival” (Seattle Times, May 18, 2010); Paul DeBarros “Funk and Soul History” (Seattle Times,2004, reprinted “Jackson Place; Heart of Seattle” retrieved December 25, 2017) “The Black On White Affair; Bold Soul Sister, Bold Soul Brother” (discogs.com, retrieved December 25, 2017); DJ Supreme la Rock “Rare Unreleased Black On White Affair” (True Player For Real, December, 21, 2008); Robert Nebitt “Wheedle’s Groove: Seattle’s Finest In Funk & Soul 1965-75” (Light In The Attic, lightintheattic.net, retrieved December 25, 2017); Andrew Gilstrap “Wheedle’s Groove: Seattle’s Forgotten Soul of the 1960’s and ’70s” (PopMatters, MY 10, 2011); Lily Mao “Slow And Steady: Engineer Kearney Barton Stays the Course 50 Years On With Wheedle’s Groove” (Electronic Musician, Oct 31, 2009; Kurt B. Reighley “The Big Payback; Seattle’s Old-School Funk & Soul Scene Finally Gets Its Due” (The Stranger, August 19, 2004); Dave Segal “Wheedle’s Groove Spotlights Seattle’s Rich Soul/Funk History” (The Stranger, May 26, 2010); Greg Barnes “Black & White Affair, Seattle Washington, 1967-1974” (Pacific Northwest Bands, August 2002); “Wheedle’s Groove” (NW Film Forum Calendar, retrieved December 25, 2017); Case Bloom “Interview With DJ Mr Supreme aka Supreme La Rock” (Tucker and Bloom, September 3, 2014); Quintard Taylor “The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District From 1870 Through The Civil Rights Era” (University of Washington Press, 1994); Joe Tangari “Wheedle’s Groove; Seattle’s Finest Soul and Funk 1965-1975” (Pitchfork Magazine, April 12, 2005); Still photo of The Black and White Affair taken from the film “Wheedle’s Groove” Photographer unknown.

The Spanish Castle is where I saw Kent Morrell and the Wailers and Marilee and the Turnabouts. Never have been able to figure out how Louie Louie is attributed to the Kingsmen not the Wailers?

It’s difficult. The Wailers were the first to record the song at Kearney Barton’s studio in Seattle (1961). Some of the members walked in one day to find another local artist was finishing up a version (Overton Berry?). They had an acetate made up immeadiately and got it to Pat O’Day at KJR the same day. The Wailers version was actually released in 1963 but it became the “hit” probably because of better promotion. The Wailers were at odds with their record label at the time and their recorded version of “Louie Louie” was originally credited to “Rockin’ Robin Roberts” – although I can’t imagine anyone NOT knowing it was really The Wailers…their version fell through the cracks nationally, but was a regional hit. Both the Wailers and the Kingsmen are actually “covers” of the orginal song written by Richard Berry and released in 1957. It becomes even more complicated. Berry was sitting in with a band in LA called The Rhythm Rockers’ They did a version of René Touzet’s “El Loco Cha Cha” that inspired Berry to write “Louie Louie” Berry claimed the song was influenced by Chuck Berry’s “Havana Moon”Berry and Frank Sinatra’s “One For My Baby

Berry’s version became a west coast “hit” and practically every northwest band was doing a cover of it for a couple of years. His back-up band on the song was The Pharoahs. It’s actually Berry who is the uncredited hero to this story. His song was credited to hundreds of bands and writers until the mid-1980s when a settlement finally paid him at least part of the majority of his royalties. Good thing too…he was living on welfare for several years. Anyway I take your point re; The Kingsmen vs The Wailers. It was all about who had the better national distribution and promo teams back in those days. And of course there were the whims of DJs and music promoters-as well as payola and luck. I think the Wailers version was originally released by Jerden Records which was a regional powerhouse at the time and were able to get much better distribution than Etiquette Records, the label the Wailers had formed to get around their contract with Golden Crest whowas no longer interested in them when they refused to move to NYC. That’s why The Wailers version was originally credited to Rockin’ Robin (who was no part of the Golden Crest deal, since he joined The Wailers a couple of years after the Wailers initial contract.

Glad to hear you got to the Spanish Castle. I’m just a young’un at 62 years so was never old enough to go there. I remember my parents driving by several times and pointing it out. The were regulars there, as well as a nearby dancehall called “The Silver Dollar” that you could see from the Freeway. IIRC, the Silver Dollar featured more country and hillbilly bands.

I can’t give a logical answer why it is that “Louie Louie” is attributed to The Kingsmen rather than anyone else except to say it was a lucky break. Here’s the REAL original version, though even this is influenced by at least three other songs!

https://youtu.be/z-2CKsaq5r8

Dennis

Does anyone know what happened to David Dominick?

I played with Black & White Affair in 1973 74. We opened for Earth Wind & Fire in Oakland CA. Lots of stories