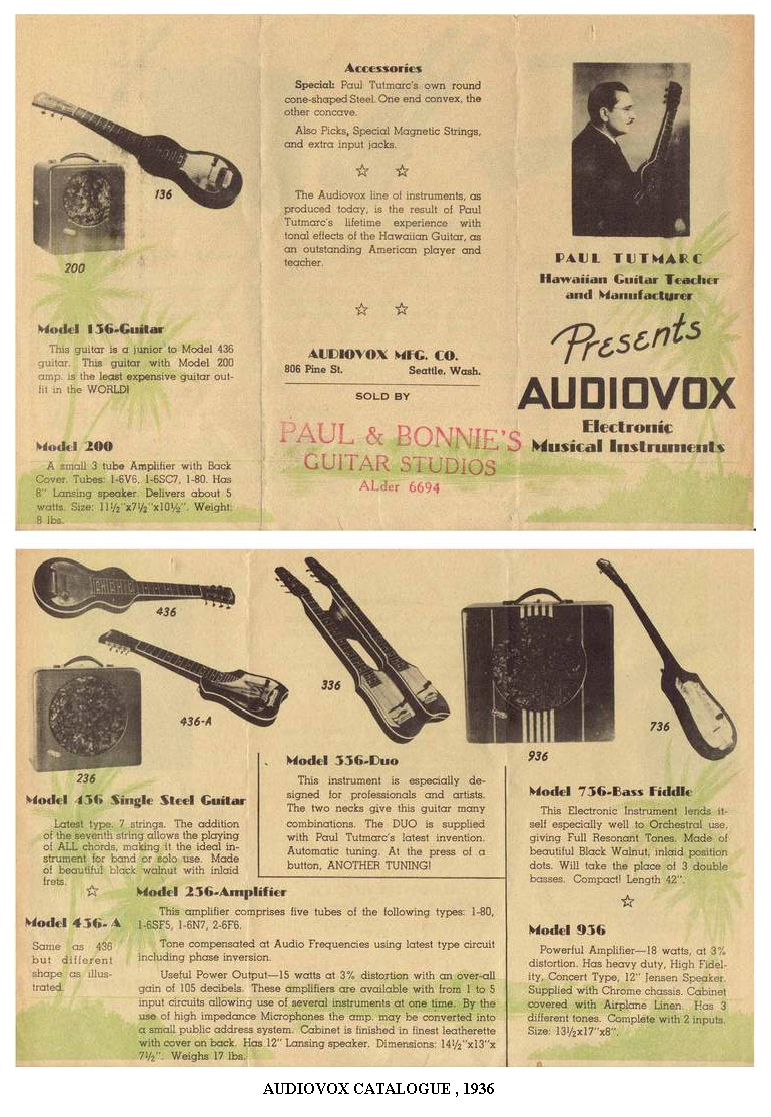

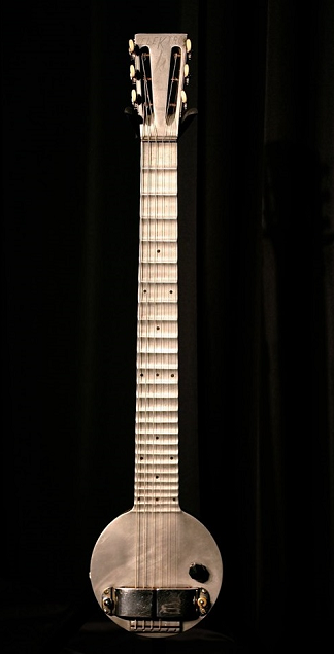

On March 6, 2018 a very special guitar was sold on ebay. It was auctioned off by Dale and Bev McKnight, an elderly couple living in a mobile home park in Snohomish WA. Dale had originally bought the guitar in Seattle in 1947 and after over 60 years of dragging it around it found its place under the bed of their home in their trailer. The buyer was David Wallis, a retired electrical engineer and guitar collector from Georgia. Wallis paid $23,850.09 for the guitar-probably a bargain for an instrument so rare. The guitar Wallis bought was an Audiovox 736 Electric Bass guitar; an instrument that some believe to be the first electric guitar…or at least the first electric bass guitar ever made.. It was Seattle inventor/engineer/tinkerer and musician Paul Tutmarc that had produced the first version of his 736 Electric Bass in 1935 or 1936. Today there are only four known to exist. Two are in private collections, and now Wallis will make his the third in a private collection. The fourth Audiovox 736 known to exist is displayed at Paul Allen’s Seattle Museum of Pop Culture (MoPop); formerly known as the Experience Music Project or EMP). Local music chronicler and former chief curator at the EMP Peter Blecha tells the story of the Audiovox 736 displayed in the MoPop/EMP museum, In an April 1, 2018 letter he wrote

“By the late 1980s I was quietly picking up Audiovox guitars and amps wherever I could find them. Thrift shops, antique stores, and guitar stores mainly, plus via the occasional classified ad. The fact is, there was no demand for them and so once these shop owners knew I was interested , they would call me to inform that another had popped up. Back then I was scooping them up for $25, or $50, or $75. One place that was always interesting to scour was a very odd ramshackle store in Tukwila. The proprietor, Jake Sturgeon, did appliance repairs/sales there and was well-connected with the local Country music scene, so he also had an array of guitars stuffed in there too. I bought a few Audiovox units from him, and he understood that I was the prime collector of the things. So, in about 1996 — 4 years into my employment as curator with Paul Allen’s museum project — I got another call from Jake. This time he was rather excited and said he had just acquired a “weird 4 string” lap steel guitar” from a little old lady” and wondered if I wanted to come by and see it. I was there within the hour. The “weird 4 string laptop” proved to be the very first Audiovox 736 Bass Fiddle to have publicly surfaced. By that point I was already well into planning the “Quest for Volume: A History of the Electric Guitar” exhibit for the EMP and knew that this would be it’s star attraction.

Becha adds;

“In 1998 I invited about five of America’s top guitar historians to Seattle to attend what I grandiosly named “The Guitar Summit.” They flew into town and we spent 2 or 3 days reviewing my exhibit plan outline, and the guitars I had lined up for inclusion in the Quest exhibit. I gotta say that of all the amazing instruments we reviewed, that Audiovox Bass was the mind-blower. Not one of the historians had ever seen or even heard of one before. In time, I found the matching Audiovox amplifier to accompany the Bass. And short story long: that pair of artifacts has been on exhibit at EMP/MoPop ever since the museum’s Grand Opening in June 2000. Whereas every other inaugural exhibit in the museum has been replaced over time “Quest for Volume: A History of the Electric Guitar” remains. A few years back one recent director there informed me that they consider “Quest” to be the “Crown Jewel” of the museum and that it is truly a permanent exhibit.”.

A MUSICAL DYNASTY

Paul Tutmarc, who’d created the Audiovox Bass Fiddle was and is the scion of a Seattle music dynasty. He was born in Minneapolis in 1896 and studied guitar and banjo as a child. At aged 15 he also fell in love with the Hawaiian Steel Guitar. As a teen he worked with traveling vaudeville troupes playing and singing.. In 1917 Tutmarc moved to the Northwest to work in the shipyards. He met and married his first wife, Lorraine in 1921. They had two children, Jeanne and Paul Junior (known as “Bud”). Paul Jr. was born in 1922 and would become a respected musician in his own right. Jeanne came along in 1924

The elder Tutmarc became known for his crystyline tenor voice and dapper appearance, as well as being a regular performer on Tacoma station KMO where he picked-up the nickname the Silver-toned Tenor. KMO was the only network-affiliated radio station in Western Washington (NBC). By 1929 Tutmarc had begun working the Seattle theaters as a tenor soloist with a number of the top dance orchestras, including those of Jackie Souders, Jules Buffano, and the town’s premiere bandleader, Vic Meyers. That same year he was performing with Stoll’s Syncopaters. Stoll was musical director for Mario Lanza and urged Tutmarc to re-locate to Los Angeles and its proximity to the to Hollywood studios. Tutmarc made barely a mark in two moving pictures, possibly Sam Wood’s 1929 feature, It’s a Great Life and a celebrity newsreel (The Voice of Hollywood # 7)

After failing to catch fire in Hollywood Tutmarc returned to Seattle and continued his work as a vocal tutor and teaching guitar. Originally he worked out of the home studio he’d built as part of a new house at 2514 Dexter Avenue North, overlooking Lake Union. Later he set up a studio in the downtown Seattle Skinner Building which also housed The Fox 5th Avenue Theater. The theater is notable in that it is one of only a handful of pre-war theaters in Seattle that have escaped the wrecking ball. After years of neglect, the theater’s Chinese Forbidden City motif was restored in all it’s glory in 1980, and it now is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

As Tutmarc become more well-known he began to perform in concert halls, continued on the radio and various theater circuits as well as with Sam Wineland’s Broadway Orchestra at Tacoma’s Broadway Theater. In 1928 the Tutmarc’s moved to Seattle where he began a stint on KJR radio and performed on the Pantages and Orpheum circuits, as well as for the brother/sister ballroom dancers Fanchon and Marco (Wolff) who had created a west coast franchise of theaters. Tutmarc was also known locally as a musician, tutor and inventor. By the 1930s he was a popular performer on local Seattle radio as a soloist and as a member of several, mostly Country and Hawaiian bands. It may seem counter-intuitive, but the earliest electric guitar aficionados were almost equally dispersed between the two genres, and both communities were responsible for the growing popularity of lap steel guitars Aside from his Country outings,Tutmarc was also respected as an important populizer of the Hawaiian lap steel guitar on the local level, a love he passed down to his son Paul “Bud” Tutmarc.

Paul Tutmarc and his first wife Lorraine divorced in 1943, and about a year later Tutmarc married his second wife, Bonnie Buckingham, who’d been one of his students; Tutmarc was 27 years older than Bonnie. By this time Tutmarc had moved his studio to 806 Pine Street in the Western Laboratories Building. Paul Tutmarc had initially built each of his guitars by hand…now a neglected art that was once practiced by the builders of stringed instruments known as luthiers. As demand for his steel guitars (and later bass laptop guitars) escalated, Tutmarc tried to keep up with the demand. Both Bonnie and Paula (along with Bud Tutmarc and other members of the family) would go on to their own place in NW and national music history. Soon Paul and Bonnie, also from a musical family with her owndreams of stardom were performing at venues such as Eagles Nest Lounge in the Eagles Auditorium building (still standing and also registered as a National Historic Place) the Elks Club and the Surf Theater Restaurant.

Tutmarc continued his figure as a dashing man about town, all the while tutoring voice, and performing with Bonnie. In 1944 the Tutmarc’s were introduced to a man named Buck Ritchey, a country/western DJ at Seattle’s KVI radio. At the time Ritchey was promoting a country band called the “K-6 Wranglers (or variously as the “K-VI Wrangles” as a reminder of his station’s call letters). Eventually Jack Guthrie would join the K-6 Wranglers. Jack had already found a bit of fame as the co-writer (along with his brother Woody) of the standard “Oklahoma Hills”

The Tutmarcs were relatively new to Country music, but it didn’t take long before they’d mastered it, with Bonnie on vocals and a National Spanish Electric Guitar and Paul playing one of the Audiovox Steel Lap Guitars that he’d been producing since 1934. The band was featured on KVI’s “K-6 Wranglers Show” which aired from 1944 through 1947. “The K-6 Wranglers” released their first single on local Morrison Records in 1948 (The Two-Timin’ Yodeler b/w The Old Barn Dance). Both songs were written by Bonnie. The Tutmarcs also recorded “Sailing Through The Sunny San Juans” and “Old Montana Cowboys” for Morrison. In 1950 the Tutmarcs began recording for Rainier Records, another (obviously) local label.

By 1950 the Tutmarcs were recording country tunes like “Cowboys Serenade” and “Ain’t You ‘Shamed” for a new local label, Rainier Records. One of the Wranglers shellac records released by Rainier is still available on the collectors market. “Midget Auto Blues” b/w “Everybody Knew But Me” are both seminal hillbilly-cum-country recordings.

During this period the Tutmarcs were also playing two nights a week at the Seattle’s Silver Dollar Tavern (not to be confused with the famous Silver Dollar Dancehall in Des Moines) Bonnie became a featured vocalist with The Abe Brashen Orchestra and Wyatt Howard’s Orchestra at the Town & Country Club in downtown Seattle.. She also recorded “If You Would Only Be Mine” with the Showbox Theater’s Norm Hoagy Orchestra for Listen Records, and in 1952 Listen Records also released two pop tunes (“Don’t Blame Me” b/w “I’m In The Mood For Love“) under the pseudonym “Candy Wayne”.

In 1950 Bonnie and Paul’s only child was born…Jeane and Bud’s new half-sister, Paula. The couple built a new home at 2514 Dexter Avenue North, overlooking Lake Union in Seattle. By that time Bonnie was trying to launch a solo career, calling herself “Bonnie Guitar. She’d been urged to demo some of her songs in both Seattle recording studios as well as in Los Angeles, but it wasn’t until she recorded the demo of a song, “Dark Moon”at Seattle’s Electricraft Inc. that her career headed for stratospheric heights. Somehow the demo made its way to Los Angeles producer/promoter and record label owner Fabor Robison. Robison had a fairly hefty roster of successful artists on his self-named Fabor Records, In 1957 he signed Bonnie and with his pull in the music industry Bonnie Guitar’s “Dark Moon” became an international hit after Robison licensed it to Dot Records. Bonnie’s career not only included being a recording star, but probably the first woman producer in the music business and a major label A&R executive for Dot Records and later Columbia.

“MIDGET AUTO BLUES BY PAULTUTMARC AND HIS WRANGLERS

Slick Henderson-Accordian, Bill Klein-Bass, Paul Tutmarc-Steel Guitar, Bonnie Tutmarc-Spanish Guitar& Vocals. Written by “Bonnie Guitar” Tutmarc

By the age of 15 Paul and Bonnie’s youngest daughter Paula had begun singing and writing while attending Orting high school. She had moved to Bonnie’s ranch south of Seattle after the split between her parents I 1955. Her mother took Paula into Kearney Barton’s Audio Recording studio. Paula spent her career using stage names and the first one she chose was Tamara Mills. She recorded her first would-be single under that name. Her mother produced the studio session that resulted in master recordings of two original compositions: “Fool’s Hall of Fame” and “Mr. Raindrop.”

According to music historian Peter Blecha who was a friend of Paula

“The plan, evidently, was to have Jerden release a single, but for reasons now lost, the project did not get further than having the two songs mastered at ‘United Recording Corporation’ in Hollywood. Those Tamara Mills tunes would likely be totally forgotten today except that in recent years a California-based record collector unearthed a ‘United Recording’ acetate reference disc of the songs which are pop with a garage-rock edge”

Paula later found a bit of celebrity during the 60s going by the stage name Alexys. In October 1965 she released her debut single “Freedom’s Child” b/w “The Evolution of Alexys”. The single was picked up on local radio and became a regional hit. As Alexys, Paula became a part of Seattle’s folkie/hippie movement and her success led to sharing stages with bands as diverse as the Beach Boys, Gary Lewis and the Playboys, The Beau Brummels The Mojo Men, and The Yardbirds while Jeff Beck was doing his stint with the band.

Alexys was signed to Dot Records-obviously the work of her mother, Bonnie. Bonnie was also instrumental in the early days of The Northwest Sound by launching the careers of The Fleetwoods, Vic Dana, The Frantics and The Ventures on her and her business partner Bob Reisdorff’s Dolton Records. The label itself was short lived so Bonnie moved to Hollywood to continue her recording career. By the time Paula/Alexys made her debut, Bonnie was the most successful performer in Country music.

Meanwhile Bonnie’s stepson “Bud” Tutmarc continued making his way as a performer and recording artist with the invaluable help of Bonnie. In 1966, the year Alexys released her debut single on Dot Records, Bud released his first full length album “Rainbows Over Paradise”…also on Dot Records. It was his only major label release but Bud would go on to combine his love of Hawaiian music with his passionate Christian faith, recording over 25 spiritual albums, acting as the musical director for The Calvary Temple (now known as Calvary Christian Assembly), and directing The Northwest Youth Choir for many years. He also ran his own independent studio, Tutmarc-Summit Studios, where he recorded his own music and produced others’, Over the years Bud Tutmarc shared his ministry with music, on radio, as a volunteer and as a charitable donor.

“Bud” died in 2006, and left behind another Tutmarc-Shane Tutmarc who had first found indie success around the Northwest with his band Dolour. Shane was doing well, but just not well enough to make a mark beyond his fans. After several attempts and riding an emotional rollercoaster Shane decided to retire from music in 2004. He left music in a fit of gloom but within a year he had come to a greater understanding of his role, and tried again.

In 2007 Shane told Tom Scanlon of the Seattle Times that after his grandfather Bud Tutmarc passed away in 2006;

“It brought me closer to my family and I decided to put together a family band Shane Tutmarc & the Traveling Mercies”.

The band featured Ryan Tutmarc (Shane’s cousin) on bass and Brandon Tutmarc (Shane’s younger brother) on drums. This is perhaps what Shane had been most lacking: a solid, stable backing band. The Travelling Mercies recorded two critically acclaimed albums-“I’m Gonna Live the Life I Sing About in My Song” and “Hey Lazurus!”-.before Shane’s going solo and moving to Nashville where he still records and produces.

So now we know a bit about the Tutmarc dynasty it’s time to ask the unanswerable:

Who Invented The Electric Guitar?

Both Les Paul and Leo Fender have been given far more credit than they are due in the evolution of the electric guitar. Each made design improvements and technical leaps, but the fact is the electric guitar has been around for over a century. What’s more, aside from design and slight adjustments, the basics of the electric guitar have remained constant since even before the earliest version was built.

We might point to (or blame) the French physicist André-Marie Ampère (yes the term “ampere” is named for him). Ampère was one of the founders of what we today know as electrodynamics”. In September 1820, his friend François Arago showed the members of the French Academy of Sciences a new discovery by Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted. The discovery was elegant in its simplicity: that “a magnetic needle is deflected by an adjacent electric current”.

Ampère set out to apply mathematics and physical laws to refine what Ørsted had theorized. The eventual result was what is known as Ampère’s Law. First Ampère demonstrated that two wires carrying electrical currents running parallel to each other would attract or repel each other depending on the direction the electrical current was travelling. This was the advent of “electrodynamics”. Ampère took this phenomena even further. If your eyes are already glazing over, this one is a bit harder to wrap one’s mind around.

Further experimentation led to the conclusion that the mutual action of wires carrying an electrical current is proportional to their lengths, and could be further controlled by the amount of current the wires decreased or increased their power-or intensity. Ampère not only created and proved his own law, he aligned it up to the work of Charles Augustin de Coulomb and his “Law of Magnetic Action”. The alignment of Ampère’s Law and that of de Coulomb’s became the foundation for the newly science of experimental physics and what we now call “electromagnetic relationship”

Other physicists followed suit in the study after a demonstrable an empirical theory had emerged from Ampère’s and de Coloumb’s work by showing proof of what we know as the aforementioned electromagnetism. In 1827 Ampère published his findings in the typically French, over-flowery titled “Mémoire sur la théorie mathématique des phénomènes électrodynamiques uniquement déduite de l’experience” (in English; Memoir on the Mathematical Theory of Electrodynamic Phenomena, Uniquely Deduced from Experience).

From here the story jumps across the English Channel to the brilliant,self-taught physicist, Michael Faraday. Faraday also discovered another elegant but simple example of electrodynamics…one that would eventually lead to the electric guitar-and quite a few other inventions we take for granted. In 1830 Faraday discovered the “electrical principle of induction”.

Electric guitars rely on one, two or more“pickups” These pickups are nothing more than a coil of copper wire wrapped around a magnet. Because of the “electrical principle of induction”, when steel strings vibrate in the vicinity of these pickups an electromagnetic signal in the copper wire wrapped around the magnet occurs.. The signal that is produced can run from the guitar, to an amplifier through a cord. The amplifier increases the signal and it moves on to a speaker so the listener may hear the result. BTW, we’ve tread into such theoretical territory, let’s pass on explaining how an analog speaker or microphone works. This explanation may have already made the reader fall asleep, and I admit I’m no physicist or electrical engineer, but I’ve described all of this in a way I myself can understand, though it might not be the exact narrative. I’m sure I’ll hear from those who have corrections. If you follow this; good; if not, you may become more appreciative of how that Ted Nugent solo relates to something that goes back centuries and involves far more intellect than Nugent could ever summon up.

In 2016 writer Ian S. Port covered a three day symposium held at The Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum. A larger gathering of historians, musicians, electrical hobbyists in the manner of Peter Blecha’s so-called 1998 “Guitar Summit” One big difference; the purported objective was to answer the question “Who Really Invented The Electrical Guitar?” Port reported on the symposium in the May 25, 2016 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine. It’s an enlightening article but it’s hard to believe that the symposium would or could answer the question of who invented the electric guitar. It seems the gathering was more geared toward the joy of discussing electrical engineering, musical tastes, trading stories about guitars, showing off beloved instruments and generally using the question at hand as an excuse to have a good time. It was a gathering of electrical geeks with guitar geeks, and probably more than a few attracted to the bar. The inclusion of guitar geeks is self-evident, but the fact is over the past century and a half it has been electrical tinkerers who have driven the creation and evolution of the electric guitar. There are very few advances in the electric guitar that have been made principally by musicians. Of course Les Paul is an exception to the rule; so is the long forgotten genius of electronic swing music, Alvino Rey. But it has been physicists, amateur radio operators, electronics fans as well as old men puttering around in basement workshops who have added more to the evolution of what we think of as an electric guitar.

One reason we cannot attribute the invention of the electric guitar is that there are so many definitions of what an “electrical guitar” is, and so many men and women that were doing the tinkering to develop it. These tinkerers were often isolated from one another, some found each other as hobbyists, and a few auspicious meetings proved critical. A lot of it was happy coincidence and some was co-opting the technology of one field to apply to another.

According to Ian S. Port who covered the Kansas symposium:

(Faraday’s) principle of induction is so simple and useful that devices based on it were widespread even before the 1900s. Telegraph keys used it, and some telephones did, too, though the first ones used primitive carbon mics. (The word “phony” comes from the awful facsimile of human speech produced by the early telephone.) Human communication was crucial in spreading the technology that would eventually become the electric guitar. ‘No one would have cared about this if it wasn’t initially about talking’ (over the telephone) Lynn Wheelwright, a guitar historian and collector, explained.”

Port goes on to write;

“A 1919 magazine ad offered a device for amplifying sounds, which, it said, could be used to amplify a violin—or ‘to spy on people’. Another magazine from 1922 touted an amateur-built “radio violin”: basically a stick with a string and a telephone pickup connected to an amp and a metal horn.

“Weak tones can be amplified by a radio loudspeaker,” the caption explained. Later that decade, a few proto-rock-‘n’-rollers figured out that by shoving a phonograph needle into the top of their acoustic guitar, they could get sound to come out of the speaker.

They were a long way from “Free Bird,” but the basic idea was there”.

ELECTIFIED!

The first person to patent a device to power an electrified instrument resembling a guitar was an American Naval officer named George Breed. In 1890 he was granted a patent for his “Method of and apparatus for producing musical sounds by electricity.”

As Port puts it:

“ it employed electricity to have the machine play the instrument. It was a self-playing guitar more than a century before the self-driving car.”

According to the Popular Mechanics story;

“Matthew Hill, who studies the history and development of musical instruments, built a replica of Breed’s guitar based on its patent, and found that the complex electromagnetic system actually vibrates the strings. The guitar plays itself, in other words, producing an ethereal, metallic drone”.

“Unfortunately the replica weighed more than a dozen pounds and is entirely impractical” he concluded.

One thing that should be patently obvious should be mentioned here. Up to the 20th century electrical currents weren’t as easy to get as plugging into an electrical outlet on the wall. All experiment had relied on batteries, creating one more hurdle for physicists and practitioners of electrodynamics to achieve their goals. It wasn’t until the dynamics and the growing access of electric availability that individuals could experiment on a wider scale.

With more availability to electricity, more and more electronic hobbyists and guitar makers were chasing the idea of electrified instruments, and even by 1900 the principles of Faraday and his earlier French counterparts were being put to use. According to Ian S.Port’

‘From 1919 until 1924 a quality control manager for ‘Gibson Guitars’, Lloyd Loar was working with pickups and amplifiers. He had built a prototype of what he called an “electrified harp guitar” which would later become known as the “Vivitone Accoustive Guitar”.

After his contract ended Loar left Gibson because of their lack of support for his creations. But while he was still at Gibson, in late 1923, he is said to have built at least one prototype for an “electrified harp guitar” It is now in thet collection of noted guitar collector Skip Maggiora, owner of Skip’s Music stores in Sacramento, California and a series of smaller local chains across the country. Maggiora thinks he knows the history of the “Vivitone Accoustive Guitar”. He appeared in a Smithsonian documentary “Electric! The Guitar Revolution’ His explanation was that by 1924 when Loar’s contract with Gibson expired he left, as we already know. At the time Gibson was more interested in relying on its sales of acoustic instruments-mostly banjos and mandolins. It was realistic for them to manufacture and sell proven money makers than fulfill Loar’s dreams. According to Maggiora, Loar took his “electrified harp guitar” with him, sold it to an hotel orchestra musician and it was passed down by the unnamed musician’s family until it was discovered in 1975.

This makes for a great story-until one realizes electrical amplification was not around in 1923 when Loar is said to have invented his instrument. Whether Maggiora had perpetrated a hoax or was duped is unclear, but the portion explaining Maggiora’s “electrified harp guitar” was later excised from the film.

It is certain that Loar did later produce and sell a line of “electified harp guitars” but the “Vivitone Accoustive Guitar” in Maggiora’s collection is probably a second or third generation example from the late 1930s. Loar is reported to have also built his own electrified bass guitar; but it is said to have a nasty habit of electrocuting players. There are also reports of Loar creating an electrified viola. In 1933 he’d created his own company Vivi-Tone to market his combination of acoustic and electrified instruments but his attempts did not catch on. In a short Vivi-Tone began to produce and sell the more popular and established keyboards.

In 1928 The Stromberg–Voisinet company of Chicago began touting a new guitar for the consumer market. The venerable “Music Trades” magazine (which has been continually published since 1890) ran a now-famous article/advertisement from Stromberg–Voisinet entitled “New Sales Avenue Opened with Tone Amplifier for Stringed Instruments.” The announcement was published on Oct. 20, 1928, claiming their new Stromberg-Electro was:

“an electronically operated device that produces an increased volume of tone for any stringed instrument.”

The ad went further to say;

“The electro–magnetic pickup is built within the instrument and is attached to its sounding board. The unit is connected with the amplifier, which produces the tone and volume required of the instrument.Every tone is brought out distinctly and evenly, with a volume that will fill even a large hall’

This was a welcome announcement for guitarists playing in Hawaiian bands as well as the nascent swing,country and big band orchestras where the guitar was, for all practical purposes never heard except during solos. Up until then the only technology to heighten the sound of the guitar was the resonator-a thin aluminum cone inside the steel instrument that vibrated with the strum ot the strings, thus amplifying sound. Often there were up to three resonators within a guitar and most steel guitarists were playing their instrument horizontially which made it even more difficult for audiences to hear. The slightly amplified sound resonators produced was driven out of the guitar’s sound hole. The resonator was not as effective as guitarists hoped, but resonating steel guitars are still popular with musicians for their unique sound.

Finally guitarists believed their electrified instruments wouldn’t be overshadowed by louder instruments. But one problem exists concerning the Stromberg-Electro; no examples of the Stromberg-Electro have been found, so it’s questionable if one (beyond a prototype) was ever built. In 1928 Henry Kay Kuhrmeyer became the president of Stromberg-Voisinet and the company was soon absorbed in to Kay’s own company, (“Kay Musical Instruments”), Kay’s new company, was formally established in 1931 from the assets of Stromberg-Voisinet. The company did later introduce a line of electrical guitars, but under the spelling “Elektro”

Guitar historian Lynn Wheelwright, former guitar technician for Alvino Rey and a great friend of Rey’s was one of those who attended the Wichita symposium. He thinks one of his guitars might have an old Stromberg pickup, but he’s not sure. Experts have found no other mentions of the guitar from this period, and have found no instruments to prove that any models were actually exist. It’s clear that Kay (and the later Kaykraft label) continued to manufacture acoustic instruments under their own name and for several other companies. Some historians claim a few Stromberg-Electro guitars were produced for the market, making it the “first” electric guitar; but as said above, not a single one has been located, and Kay Musical Instruments did not issue an electric guitar until 1936 — five years after the Rickenbacker Frying Pan, and the same year the Gibson ES-150 was introduced.

The Rickenbacker “Frying Pan” was originally designed by George Beauchamp (pronounced as Beech-um in one of the English’s confounding ways to make spelling and pronunciation more complicated). Beauchamp, a Hawaiian lap guitar player, like other steel guitar players had been looking for a way to make their instrument heard above the din of other louder instruments. Beauchamp had helped develop the Dobro resonator guitar, and co-founded the National String Instrument Corporation After months of trial and error Beauchamp created his own pickup that consisted of two horseshoe magnets. The strings passed through these and over a coil, which had six pole pieces concentrating the magnetic field under each string. It’s said he initially used a washing machine to wind up the coil. At the time poor “Bud” Tutmarc was doing it by hand.

After determining that the horseshoe pickup actually worked Beauchamp approached Harry Watson, a luthier who’d been superintendent of the National String Factory in Los Angeles. Watson crafted a wooden neck and body to create a prototype. In several hours, carving with small hand tools, a rasp, and a file, the first fully electric guitar took form. It was dubbed (like others) as the world’s first electric guitar, even though it’s production model was actually made of aluminum.

Beauchamp then enlisted the help of his friend, the Swiss-born Adolf Rickenbacher. Adolf had anglicized his name slightly to Adolph Rickenbacker and was cousin of the famous flyer Eddie Rickenbacker. Adolph had plenty of capital and owned a company that created the aluminum resonators for instruments. Beauchamp and Rickenbacker joined forces and a company was formed to manufacture and sell the guitar that would fondly be known as the “Frying Pan” guitar. The initial name of the company was Ro-Pat-In Corporation then changed to Electro String.

According to the official Rickenbacker website;

“When Adolph became president and George secretary-treasurer. they renamed the company Rickenbacker because it was a name known to most Americans and easier than Beauchamp to pronounce. Paul Barth and Billy Lane, who helped with an early preamplifier design, both had small financial interests in the company as production began in a small rented shop at 6071 S. Western Avenue, next to Rickenbacker’s tool and die plant. (Rickenbacker’s’ other company still made metal parts for National and Dobro guitars and Bakelite plastic products such as Klee-B-Tween toothbrushes, fountain pens, and candle holders.)”

Although the official model name of the new guitar was the Rickenbacker Electro A-22 but it soon became known as the Rickenbacker Frying Pan for obvious reasons. It’s small round body attached to its long neck is, in fact, reminiscent of a frying pan. The fact that it was all aluminum also came into the equation.

“By the 30s the electric guitar had found more popularity, and so a race to create a consumer-friendly electrified instrument became paramount. Electro String (the parent company of Rickenbacker) had several obstacles. Timing could not have been worse–1931 heralded the lowest depths of the Great Depression and few people had money to spend on guitars. Musicians resisted at first; they had no experience with electrics and only the most farsighted saw their potential. The Patent Office did not know if the Frying Pan was an electrical device or a musical instrument. What’s more, no patent category included both. Many competing companies rushed to get an electric guitar onto the market, too. By 1935 it seemed futile to maintain a legal battle against all of these potential patent infringements”

The Rickenbacker Electro A-22 was only produced between 1932 and 1939 and it did not receive a patent until 1937. Even though the Frying Pan was not a commercial success at the time, it is popular among today’s collectors, and plenty of guitarists have been known to perform onstage with them.

THE FIRST KING OF ELECTRICS

But it was the near-criminally forgotten band leader and pioneer of the electric guitar Alvino Rey (born Alvin McBurney) who was known for his mastery of the Hawaiian laptop guitar and later the pedal steel guitar. He became wildly popular onstage later about 1933, He began to be shown in national magazines with the newly available electric guitar. Rey himself came to music through his love of electronics and experimentation with it during his boyhood. It’s said he was constantly taking telephones and other gadget apart and putting them back together to understand how they worked. Aside from popularizing the electric guitar Rey also contributed other important musical innovations.

He was, and still is called “The First King of Electrics” by his millions of fans.

Since Rey had been known for his laptop guitar playing in 1935 Gibson asked Rey to create a prototype with engineers at the Lyon & Healy company in Chicago. The laptop steel guitar had the disadvantage of it’s sound being directed vertically rather than directly at the audience. The laptop guitar needed amplification as well as the electric pedal steel guitar that was becoming popular among Hawaiian and Country and Western artists. Rey himself was probably the most influential early guitarist for popularizing the pedal steel guitar.

Rey’s prototype resulted in Gibson’s first electric guitar, the ES-150. Many people refer to the ES-150 as the first “modern” electric guitar-though it could easily be argued one way or another. Rey’s original ES-150 prototype guitar is now also on permanent at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture (formerly EMP)

Speaking of their guitar collection, Jacob McMurray, senior curator at the EMP/Museum of Pop Culture;

“There’s Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock guitar, Eric Clapton’s Brownie, which he played on “Layla,” and there’s Alvino. Rey helped develop that prototype as a consultant for the Gibson company, but how he played was also an innovation”

Rey was also known for introducing an incredible novelty, “Stringy The Electric Guitar ”using what Rey called the “Sono-Vox” Part technology and part artifice, a July article in Dangerous Minds explains:

Alvino Rey on Electric Steel Guitar with “Stringy The Talking Guitar”. Vocals by Andy Russell

“Rey, using his steel guitar, appeared to be creating the singing voice for bizarro “Stringy The Talking Guitar.” In fact, it was Rey’s wife Louise, in tandem with Rey’s guitar sounds, that created the effect. Louise was backstage with a carbon throat microphone attached to a piece of plastic tube running to Rey’s amplifier. She would provide the words and Rey would alter them by sliding the steel bar along his guitar strings. Alvino and Louise were able to create some otherworldly sounds using this technique, including the weird voice of ‘Stringy’. Rey’s invention eventually evolved into the ‘talk box’, appearing as the vocal effect on the 1976 ‘Frampton Comes Alive’ album

.

Rey himself became history’s first “superstar” or “guitar hero”, He became a celebrity that regularly sold out the venues he played, as well as a constant presence on radio. Rey recorded with Esquivel, Martin Denny, The Surfmen and played on many “exotica” albums as well as film soundtracks, including Elvis’s Blue Hawaii.

Walter Carter a former Gibson guitar company historian has said:

“For millions of radio listeners, the first time they heard the sound of an electric guitar, it was played by Alvino.”

Rey would have a long career, and ventured into the avant-garde as well as an early proponent of rock and roll. He is often referred to as the “father of the electric guitar” Although this is demonstrably untrue, it shows the amount of influence he had on the history of the electric guitar and the public’s affection for him.

Lynn Wheelwright (mentioned before as Rey’s guitar techinician and friend ) told Ian S. Port:

“You should have heard him on stage with a regular guitar—holy god!“ Alvino opened every show with a guitar solo, he closed every show with a guitar solo, and he had a guitar solo in every song. He found a way to use the instrument in such a way that people would buy them and use them.” At first, Rey plugged his guitar directly into the radio station’s transponder”, Wheelwright said. “But if the sound he wanted wasn’t readily available through his instruments, he tweaked the wires himself.

Eventually he would marry into the famously wholesome King Family and became their musical director. He became less well-known as an innovator even though he had a remarkable history in musical technology. He died in 2004 at the age of 95

We could continue with a discussion of the electric guitar in more modern times, including people like Leo Fender, Les Paul, Gibson, Bailey, et al or the merits of Rickenbacker or Mosrite over the Sears-Roebuck Silvertone guitar, but if we look into the history of the guitar and the laws of electrodynamics, we see that the electric guitar is basically the same basic instrument today that it was over a century ago. There have been design changes, improvements (notably in humbucking pickups) and the change in popularity from electrified hollow bodied guitars to solid-body guitars (which predate Les Paul and Leo Fender by decades) so now we will return to our original subject; Paul Tutmarc.

IF IT HADN’T BEEN ME, IT WOULD HAVE BEEN SOMEONE ELSE

Tutmarc continued his performing career through the 1920’s and 30s and we know he taught various stringed instruments. At the same time he continued his electronic tinkering and it’s application to musical instruments. He experimented with various types of instruments, various forms of electrified amplification and a device that would later be thought of as a “pickup”

Tutmarc’s son “Bud” reports:

“In the later part of 1930 or perhaps the very first of 1931, a man, Art Stimpson, from Spokane, Washington, came to Seattle, especially to see and meet my father. Art was an electrical enthusiast and always taking things apart to see what made them function as they did. He had been doing just this with a telephone, wondering how the vocal vibrations against the enclosed diaphragm were picked up by the magnet coil behind the diaphragm and carried by the wires to another telephone. My father became interested in this “phenomenon” and began his own “tinkering” with the telephone. Noting that taping on the telephone was also picked up by the magnetic field created behind the diaphragm, he was encouraged to see if he could build his own “magnetic pickup”.

One very important revelation in “Bud’s” story is that Stimson and Tutmarc had been fascinated by the ability of a diaphragm to transfer vibrations from one telephone to another over an electrical connection. This tells us something we may have overlooked, but should be obvious. Alexander Graham Bell’s invention, the telephone, had been putting the laws of electrodynamics into pragmatic use for decades. Bell had early patents on hundreds of devices, including telephone technology. In fact, it’s said he could be vicious in his attempts to accrue patents that he may not have been entitled to. This should also tell us why it would be so difficult for the early pioneers of the electric guitar to patent their technology. Graham had beat them to it’s technology years earlier.

About the time Tutmarc met up with Stimson he became friends with another electronics fanatic, Bob Wisner. According to “Bud” Tutmarc

‘Bob Wisner (was) a young man with a brilliant mind, and a radio repairman of great repute in Seattle as about the only one able to repair the old Atwater-Kent radios. He worked at Buckley Radio in Seattle, on Saturdays, repairing all the radios the regular repairmen could not repair during the week. It was Bob Wisner who helped my dad re-wire a radio to get some amplification of his magnetic pickup”.

Tutmarc then took an old round-holed flat-top Spanish guitar and discovered he could fit it out with a wire-wrapped magnet (essentially a pickup) inside that would carry the sound of a plucked string to hia newly-created amplifier-the modified Atwater-Kent radio.

According to his son, Tutmarc

“developed a polepiece sticking up through a slot he cut in the top of the guitar near the bridge, and the electric guitar was on its way. Being an ambitious woodworker, he decided to make a solid body for his electric guitar idea and his first one was octagon shaped at the bridge end, containing the pickup and then a long, slender square cornered neck out to the patent heads”.

Tutmarc had accomplished several things at the same time. He had put the pickup inside the guitar, he’d created a practical amplifier (with Wisner), created a solid body guitar (an innovation he’d borrowed from Rickenbacker’s 1931 “Frying Pan” lap steel guitar), and tied it up with a “polepiece” which would be one of the hallmarks of the electric guitar as we know it today.

Paul Tutmarc may not have “invented” the electric guitar, but he had brought it much closer to the combination of design and technology we know it as today.

His invention caused a lot of interest-especially among local Seattle musicians and his students….all of who were a natural consumer base for his product. Tutmarc envisioned his new operation as the “Audiovox Manufacturing Company” that would produce and market his guitar and eventually other instruments and amplifiers.

Art Stimson and Paul Tutmarc parted ways in early 1932. The partners understood the importance of what they’d achieved, but they had a difference of opinion on what to do with their discovery. Stimson wanted to sell or license the “pickup” to a larger company. Tutmarc wanted to seek a patent for the pickup’s design. It’s said that Tutmarc spent $300 on a patent search (about $5000 in 2018 dollars-a cost that might be expected to be spent today, but an enormous sum during the depression of the 1930s). At the time no patents would have been filed on the instrument Tutmarc created, but he and his lawyers were not seeking a patent on the the instrument; they were searching for a patent for the “pickup” which had already been covered years earlier by the Bell company in conjunction with the entirety of it’s telephonic gadgetry. Seeking a patent for his “pickup” technology would be a mistake that could have made Tutmarc a very wealthy man, but he wouldn’t discover it until later .Tutmarc went back to work in Seattle while Stimson left for Los Angeles where he said he was going to try get interest.

In August of 1932 Tutmarc became aware of a Los Angeles manufacturer selling an “Electro String Instrument”. The company was Rickenbacker International!

In the spring of 1933, the Dobro firm started selling their electrified Spanish-style guitar. It was obvious to Tutmarc this instrument was based on his own discoveries. What Tutmarc did not know was that Dobro had filed a patent on April 7th, 1933 for the overall design of the instrument- not just the pickup technology Tutmarc had foundimpossible to patent in 1931. It was later that he found out that the patent application named “Art Stimson” as the assignor. Besides being stabbed in the back by Stimson, Tutmarc also discovered that the pickup design (which was integral to the instrument) had been sold by Stimson to Dobro for only $600.

According to Blecha;

“Tutmarc finally forged ahead marketing his own brand of electric guitars. Though a bit late to the race now, Tutmarc became ever more determined to create a superior electric guitar and, through more experimentation, vastly improved his old design, effectively creating the world’s first slanted split-polepiece magnetic “humbucking” pickup — a design that Dobro, National, and other firms soon began emulating”

Although Tutmarc continued to improve on his design it was clear he could not compete with the big players. His instruments became popular with cream of the crop of Hawaiian steel guitar players and among the musicians who had cross-pollenated Hawaiian music with Country music. The most famous Hawaiian guitarist of the day, Sol Ho’opi’i championed Tutmarc and Audiovox in general

According to Bud, Tutmarc his father was an avid woodworker,

“but as more and more instruments became in demand he “contacted a man, Emerald Baunsgard, a young superb craftsman, and an agreement was made. Emerald started doing all the woodwork of the electric guitars for Audiovox. Emerald was a master at inlay work so these black walnut guitars all had inlaid frets, inlaid pearl position markings and beautiful, hand rubbed finishes. The guitars were beautiful and very quickly accepted on the market”.

Bud says his father also manufactured a sold-body Spanish Guitar, but there simply was no market for it.

He also says:

“My dad, being a band leader and traveling musician, always felt sorry for the string bass player as his instrument was so large that once he put it in his car, there was only enough room left for him to drive. The other band members would travel together in a car and have much enjoyment being together while the bass player was always alone. That is the actual idea that got my father into making an electric bass. The first one he hand-carved out of solid, soft white pine, the size and shape of a cello, To this instrument he fastened one of his “friction tape’ pickups and the first electric bass was created. This was in 1933”.

“The idea of the electric bass was very important to him, but he was so dissatisfied with his solid body “cello size” bass that he made a 42 inches long, solid body bass out of black walnut, like his guitars, and the electric bass was launched. The cello sized bass was too heavy and not really accomplishing what he set out to do; wanting to create an instrument, small and light-weight, yet capable of producing more sound than several upright, acoustic basses. My father advertised his electric guitars, single necked steel guitars and double necked steel guitars”. Finally his new electric bass (the Audiovox 736) was shown in a local school’s 1937 Yearbook. That certainly establishes a definite date. I personally played the electric bass in John Marshall Junior High School, here in Seattle, in 1937 and 1938”.

By this time it’s clear Tutmarc missed out on the bragging rights to claim he “invented” the electric guitar, but it seems almost sure he had invented the first electric bass guitar. The official designation for his bass was the Audiovox 736 Electronic Bass Fiddle. Instead of the traditional double bass, this model was to be played on the horizontal, not the vertical or “upright” position. Aside from it being electrified and amplified (therefore much louder than the traditional bass) it also featured a fretted neck (also unlike the traditional bass) and not particularly meant to be played with a bow. Although Audiovox guitars come up for sale now and again it seems very few 736 bass guitars were made-hence it’s rarity.

Besides instruments Audiovox also created and manufactured amplifiers designed by Bob Wisner, the man who’d first paired up with Tutmarc to turn the old Atwater-Kent radio into an amplifier. Wisner created an amplifier to accompany the Audiovox 736; the Audiovox Model 936. After his time as a repairman and electronics wizard in Seattle Bob Wisner went into scientific work. He ended up as part of the team working on the Atomic Bomb in Wendover, Utah and Alamagordo, New Mexico. After WWII Wisner worked on the Bomarc missile program at Boeing. Eventually he went to Cape Canaveral (now Cape Kennedy). Sadly Wisner died during the first American space-shot to the moon.. He witnessed the lift-off but did not survive to see the successful landing.

In 1948 Bud Tutmarc began making his own electric guitars that were distributed by Portland’s “L.D. Heater Music Company. He also went on to create his own electric bass; the Serenader. Bud believes the “L.D. Heater Music Company”was the first large distributor to carry any electric bass. Bud also created several innovations, in particular an attempt to find a way to have the steel guitar give more depth on the bass strings. He reverted to the old practice of putting the pickup outside the guitar,plaing them at various locations over the strings. He also put the a pickup six inches in front of the bridge, giving the instrument much more depth of sound. After he discovered this trick he went on to place all of his pickups on the electric bass six inches from the bridge. This is still prevelant in basses today. Bud also tried slanting the pickup so that the polepiece would be farther from the bridge under the bass strings and closer to the bridge under the treble strings. This further gave more depth to the bass strings without affecting the treble sound of the higher strings. The slanted pickup near the bridge is another of his innovations that are still commonly used.

Peter Blecha, the Audiovox expert this article has relied so heavily upon believes;

Even though Audiovox sold numerous Electronic Bass Fiddles to Northwest musicians, the instrument was so completely ahead-of-its-time that it never succeeded commercially. So, despite the trail-blazing uniqueness of Audiovox instruments, relatively few were sold, no national distribution strategy was ever implemented, and Tutmarc’s contributions basically fell through the cracks of history. All of which helps explain why the Audiovox saga went missing in all of the early electric guitar history books, and other men — like Fullerton, California’s Leo Fender (who first marketed his famously successful bass guitar in 1951) — long received all the credit for “inventing” the electric bass. Until recently Paul Tutmarc’s innovations have not been considered among the most important facets in the history of the electric guitar…and although an argument can be made that he invented the first electric guitar and bass guitar it really doesn’t matter much. The most important thing is that his place among the pioneers of the electric guitar has been restored.

It’s often been noted that Paul Tutmarc was not a fan of rock and roll and felt some ambivalence toward his creations, the electric guitar and bass. Shortly before his death in 1972 he told a newspaper interviewer “A lot of fathers and mothers probably would like to kill me. Then again, if it hadn’t been me, it would have been someone else”

-Dennis R. White. Sources; Bud Tutmarc “The True Facts on the Invention of the Electric Guitar and the Electric Bass” (http://tutmarc.tripod.com/paultutmarc.html retrieved April, 20, 2018; Peter Blecha “Tutmarc, Paul (1896-1972), and his Audiovox Electric Guitars” (HistoryLink.org Essay 7479, September 18, 2018); Erik Lacitis “Historic, Seattle-made electric bass guitar sells for $23K “ (The Seattle Times, March 11, 2018); Ian S. Port “Who Really Invented the Electric Guitar? After 80 Years, We Still Don’t Really Know”(Popular Mechanics, May 25, 2016);. Peter Blecha “Audiovox Electronic Bass: Discovered! The World’s First Electric Bass Guitar” (Vintage Guitar Magazine, March 1999); L. Pearce Williams “Michael Faraday, British Physicist and Chemist” (Encyclopaedia Britannica (retrieved April 21, 2018); Rich Maloof “Who Really Invented The Electric Guitar?” (reverb.com, June 29, 2017); Christopher Popa “Alvino Rey: Wizard of the Steel Pedal Guitar” (bigbandlibrary.com, retrieved April 20, 2018); “Les Paul Biography: Guitarist, Inventor (1915–2009)” April 27, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2018); Phyllis Fender & Randell Bell “Leo Fender:The Quiet Giant Heard Around the World” (Leadership Institute Press, 2018); G.W.A Drummer “Electronic Inventions and Discoveries: Electronics from its Earliest Beginnings to the Present Day [Fourth Revised and Expanded Version]” (Institute of Physics Publishing, January 1, 1997); Sonia Krishnan “Paul ‘Bud’ Tutmarc, who shared Christian faith through music, dies at age 82” Seattle Times, December 8, 2006); Tom Scanlon “Shane Tutmarc Finds Healing In His Roots” (Seattle Times, October 19, 2007) “Shane Tutmarc Home Page” (www.shanetutmarc.com, retrieved April 21, 2018) Peter Blecha correspondence, (April 29, 2018): Clayton Park “North Seattle Was Birthplace of the Electric Guitar, Bass” (Jet City Maven, volume 4, issue 8, August 8, 2000); “The Earliest Days of the Electric Guitar” (Rickenbacker.com, retrieved April 2, 20180; Listen to The Music [Smithsonian Channel] “Electrified! The Guitar Revolution” (first airing August 15, 2010); A.R. Duchossoir “Alvino Rey: The First King of Electrics” (Gibson Steel Guitars: 1935-1967, Hal Leonard Books, 2009).

Informative, deeply researched and well written. Kudos! Who’s the author?

I am the author of all the articles on the NW Music History site at Jive Time Records. Thanks for the compliment. I try to do a deep dive into research for everything I post here.

Dennis R. White

I have a 1932 DoBro cyclops with a electromuse pic up installed where the hole used to be and a megatone amp called a troubadour that I was told belonged to Paul Tutmarc.

It’s has a small plack on the head says Paul.

Enjoyed this article very much. Very well researched. I came here from hearing Shane Tutmarc’s tribute song to Prince and learning that his great grandfather invented the bass guitar. I also used to live in Seattle and walked past the former site of Paul Tutmarc’s studio on Pine Street never knowing the history (it’s now a parking lot across from the Paramount Hotel). Thank you for documenting this history.

Thank you for the great article. Emerald Baunsgard was my husband’s grandfather. Our family still has one of the lap steel guitars but the audio-vox amp has gone missing. Hopefully it will turn up as we would like to preserve this part of history for future generations of our family.

Paul H Tutmarc was my great grandfather. His daughter Jeanne my grandmother. You have her’s and her Brother’s, Bud, birthdays reversed. Jeanne was the older, born in 1922, Bud was born in 1924.

Very interesting article about Paul Tutmarc. I just did a Google search to see if there was any record of him. I studied Hawaiian steel guitar as a teenager and took lessons from him in Seattle. He had a warm personality and a golden tenor voice.

I have a AudioVOX electric lap steel guitar that was purchased by George Barras. He was music teacher, that played in Vaudeville, played almost all instruments. He played violin in the Seattle symphony and up in Canada. He gave me, what he said was the first production lap steel ever made in Seattle. I have the guitar and amp. I do not know where to find a model number on the guitar. It is a match to the model 136 or 436. In that old posted pamphlet. He told me bought it from the builder in Seattle.