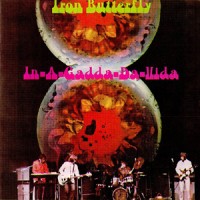

Iron – Symbolic of something “heavy,” as in sound.

Butterfly – Light, appealing and versatile… an object that can be used freely in the imagination.

On the back of their LP sleeve is this statement, and it’s fitting for a group that shows their varying chops on either side. Their particular brand of psychedelic rock on side one works, but it does seem to allude that a change in style was coming. Erik Brann’s vocals are deep and don’t really bring flowers to mind, even during the groups more flourishing numbers. Organ sounds rip holes through the mix and give a slight ominous tone to everything. Late bassist Philip Taylor Kramer (mysteriously found dead in a car at the bottom of a ravine) gave a warm tone that brings Grand Funk to mind. (EDIT: Kramer joined after the recording of I-A-G-D-V, but was most know for it in performance.)

Side one has moments of beauty with “My Mirage” and “Termination” but it’s the all-encompassing title track that really gives Iron Butterfly their claim to fame. A heavy opening with an unforgettable riff, it later turns into a psychedelic wind tunnel of driving instrumentals; guitar, drum, bass and organ-led mayhem to serenity. Along with Blue Cheer and Steppenwolf, Iron Butterfly are one of those groups that show interesting tangents from garage and psych to the world of heavy. -Wade