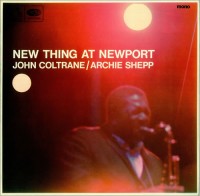

The Classic Coltrane Quartet in fine form, by 1965 they were at the pinnacle. The New Thing in question was a mix of Avant and Free music that Trane and company waded into, not immersing themselves totally in atonality. On the official vinyl album, we here the twelve minute, “One Down, One Up,” which is well worth the price of the LP by itself…

But then there is the second track and second side, and while Coltrane’s music takes us higher throughout and expresses more in ascending spurts and rips, Archie Shepp’s music revels in mid to low-tempo vibraphone rhythms. Archie himself plays sax like he’s being suffocated by a pillow, or strangled. And he staunchly reveals political leanings in spoken word moments like “Scag.”

This is a sea-change moment in Jazz, and for Coltrane in particular. A great live album by itself, the expanded CD edition is also worth grabbing for an absolutely searing rendition of “My Favorite Things” that is totally joyous and leaves the crowd screaming for more. This is right up there with “Live At Birdland” and hints the coming days and tangents of Jazz to come through two unique sets. -Wade