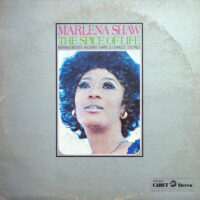

Jazz and soul singer Marlena Shaw—who passed away on January 19 at age 81—was a true American musical treasure whose abundant vocal charms and moving lyrical skills peaked on The Spice Of Life. Produced and arranged by Cadet Records geniuses Charles Stepney and Richard Evans, The Spice Of Life boasts two of Shaw’s greatest and best-known songs, “Woman Of The Ghetto” and “California Soul.” The album would be worth the price of admission just for these two classics, but it contains some other lesser-celebrated gems, too.

But first, “Woman Of The Ghetto.” Talk about putting your best foot forward… This street-level, soul-funk classic has been sampled 204 times, and that makes sense. A tense, riveting song that can stand shoulder to shoulder with Curtis Mayfield’s “Freddie’s Dead,” “Woman Of The Ghetto” finds Shaw relating a tale of woe in wrenching detail: “How do you raise your kids in the ghetto/Feed one child and starve another.” The female backing vocals scat in vibrant consolation with Shaw while kalimba accents reminiscent of those early Earth, Wind & Fire LPs, a memorably trenchant bass line, and eerie, hysterical harmonica interjections multiply the drama. Damn, this cuts deep.

As for the cover of Ashford & Simpson’s “California Soul,” it’s simply one of the most uplifting orchestral-soul masterpieces ever waxed, with Stepney and Evans’ deft fingertips all over it. If you aren’t smiling and floating to this within the first 10 seconds of this billowing beauty, go see a shrink. It’s not hard to hear why this rendition’s been sampled 35 times. “Liberation Conversation”—co-written by Shaw and Bobby Miller—is a feisty, funky highlight in the Marva Whitney vein, featuring more of that delightfully buoyant ga-ganga scatting that Shaw also emitted on “Ghetto.” “Blues ain’t nothing but a good woman gone bad,” she declares, as if speaking from bitter experience.

T-Bone Walker’s “Call It Stormy Monday” gets transformed into swanky jazz blues with gorgeously anguished guitar and harmonica parts while “Where Can I Go?” is a languidly funky ballad in which Shaw’s voice effortlessly evinces subtle shades of pride, melancholy, and regret. The loping gospel funk of “I’m Satisfied” would appeal to fans of Pastor T.L. Barrett—a very great thing, indeed. Similarly, the freewheeling paean to liberation, “I Wish I Knew (How It Would Feel To Be Free),” peddles rollicking gospelized soul. Credits are damnably scant on this LP, but that rococo, quicksilver guitar solo sure sounds like Phil Upchurch and whoever’s on organ just blazes.

A few schmaltzy cuts penned by the celebrated songwriters Goffin & King, Mann & Weil, and Johnny Marks don’t hit with this critic, but they don’t detract much from The Spice Of Life‘s overall greatness. This album shouldn’t be too hard to find nor should it be very expensive; Verve did the last official vinyl reissue in 2018. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.