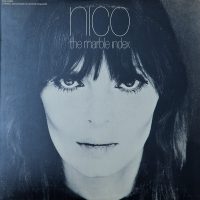

When you think about records that could be considered the antithesis of a party album (and who doesn’t, at least weekly?), you have to place Nico’s The Marble Index near the top of the heap. Recorded with fellow former Velvet Underground band mate John Cale, this record stood in stark relief against 1968’s kaleidoscopic array of vibrantly hued psychedelia and rabble-rousing soul like an ice castle in the desert. Anyone expecting another lissome folk-pop gem like Nico’s 1967 debut LP, Chelsea Girl, would have to have been shocked upon hearing The Marble Index. According to interviews, Nico is on record as saying the latter is a more true expression of her art and soul than the former, which abounded with songs written by men. Angst for the memories, Ms. Päffgen.

After the brief “Prelude,” a relatively sprightly glockenspiel and piano reverie that doesn’t prepare you for what’s to follow, things snap into proper foreboding with “Lawns Of Dawns.” The song seems to rise out of a murk, not unlike some of the tracks on Tim Buckley’s Starsailor. Harmonium drones, glockenspiel tintinnabulations, Nico’s stentorian intonations of oblique, personal poetry mark Marble Index‘s dominant mode, and it’s icy, mate. Trivia: “Lawns Of Dawns” reportedly was inspired by peyote visions Nico experienced with paramour Jim Morrison.

“No One Is There” is minimalist, Northern European art-folk lieder, as Nico trills morosely over Cale’s saturninely beauteous viola. Written for her son, “Ari’s Song” is a lullaby that probably offered cold comfort, given its frigid atmosphere and piercing bosun’s pipe tonalities. Over a slightly woozy and fragile cacophony, Nico sings, “Sail away, sail away, my little boy/Let the wind fill your heart with light and joy/Sail away, my little boy.” Sweet dreams, child, ha ha. “Facing The Wind” is haunted desolation incarnate. Nico’s waxing and waning harmonium drones slur around banging piano dissonance and random, disconcerting percussion. Our heroine sings through a Leslie speaker for added eeriness about an existential crisis exacerbated by the elements in nature.

Toward Marble Index‘s end, things really get dark. The polar viola drones in “Frozen Warnings” shiver with unbearably poignant forlornness, shrouded by Nico’s pitiless yet dulcet vocals. It’s up there with Buckley’s “Song To The Siren” for tender, heart-shredding sonic beauty. Listen and feel your blood slowly freeze with sympathy. Album-finale “Evening Of Light” features gradually intensifying bell tolling, grim bass groans, and viola drones that overwhelm Nico’s doomed crooning. Nico and Cale are not even trying to make the music and singing sync up, which adds to the sense of menace. The refrain “Midnight winds are landing at the end of time” sums up The Marble Index‘s pervasive mood of crushing bleakness and captures the song’s artfully apocalyptic tenor.

In the liner notes to the deluxe CD reissue of The Marble Index and Desertshore titled The Frozen Borderline: 1968-1970, the LP’s producer, Frazier Mohawk said: “After it was finished, we genuinely thought people might kill themselves. The Marble Index isn’t a record you listen to. It’s a hole you fall into.” The man speaks the truth. Nevertheless, you need to hear it. -Buckley Mayfield