In order to contextualize some of the best Brazilian music of the 1970s, one must first understand tropicália (AKA tropicalismo). In order to do that, one must first look back to Brazil in the ‘60s, a nation at that time rife with contradictions. Despite intermittent political instability which culminated with a military coup in 1964, postwar Brazil simultaneously experienced unprecedented economic growth. A large portion of its population lived far below the poverty line, but its middle class grew exponentially, with many of its members now enjoying a standard of living that previous generations could only dream of. Not surprisingly, these changes began to manifest themselves in the music of Brazil. Bossa nova, in particular, enjoyed not only massive popularity in its homeland but in many countries in the northern hemisphere as well, making it Brazil’s most successful musical export since Carmen Miranda. At the same time, other new styles emerged on a seemingly daily basis. Aided by a growing radio and television industry and the proliferation of the LP format, a new Brazilian musical identity began to emerge, adopting the moniker of MPB (Música Popular Brasileira). Ironically, it was also around this time that a host of distinctly non-Brazilian styles, most notably American R&B and British Invasion, began enjoying popularity there as well. From there things would only get more complicated.

By 1966, a small but growing movement was afoot in the northeastern city of Salvador. Deconstructionist and remarkably post-modern in its approach, it sought to shatter all preconceived notions about Brazilian art and culture and reassemble these pieces into something entirely new. These “tropicalistas”, as they called themselves, at first largely consisted of artists, poets, and filmmakers. But when two up and coming musicians, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, entered the fold, Tropicália’s true legacy would become realized. Soon joined by a handful of other massive musical talents, among them Gal Costa, Tom Zé, and a trio of teenage Beatles fanatics calling themselves Os Mutantes, this unlikely collective would spearhead the Tropicália movement. Incorporating disparate musical styles ranging from traditional samba to psychedelic Hendrix-style guitar freakouts into their songs, nothing was sacred to the tropicalistas. This anarchic sonic collage can be heard in all its glory on the 1968 sampler LP, Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis, which fired the opening salvo of a musical revolution that would prove to be very short-lived.

Tropicália’s tenuous existence was no surprise; in many ways, its founders were fighting a losing battle from the start. The left-wing intelligentsia thought them traitors for “corrupting” traditional Brazilian music with imperialist influences. The then in power military regime, of whom the Tropicalistas’ music openly and harshly criticized, hated them even more—so much so that they jailed and eventually deported Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil in 1969. With its two leading lights (temporarily) extinguished, Tropicália was basically over. But as far as what lay ahead for MPB, the real revolution had only begun.

For newcomers to Brazilian music, especially those steeped in a rock background, Tropicália often garners the most attention. This is not surprising, as it’s received a lot of press over the past decade and it has had some high-profile fans, Kurt Cobain and Beck among them. Much of what came after it in the following years might have lacked the aggression and visceral urgency that characterized Tropicália’s greatest moments, but the music of the post-Tropicália period was just as compelling, and perhaps even more diverse. Indeed, for many connoisseurs of Brazilian music, the early 1970’s represents an apex of innovation and excellence, a true Brazilian musical renaissance. Unfortunately, some of the best examples from this period can be tough to find outside of Brazil, but those willing to search will find the effort to be well worth it. Here are some titles to start with.

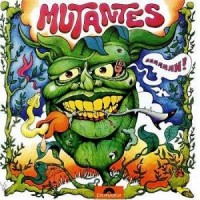

Os Mutantes Jardim Electrico (1970) Like their other later albums, this 1970 effort does not get as much attention as the “Tropicália trifecta” of their first three releases. This is not entirely fair. True, much of the endearing wackiness and Dadaist mayhem inherent in their earlier work are gone. But it’s all replaced with new-found confidence, more disciplined song structures, and tighter playing. Recorded mostly in Paris, Jardim Electrico shows the “Brazilian Beatles” vying for an international audience. One song, “El Justiciero”, is in Spanish. Two others, “Baby” and “Technicolor” are in English; the former makes a fine addition to the two versions recorded in Portuguese during Tropicália’s heyday while the latter, an entirely new creation, sums up the band’s raison d’être more effectively than anything they recorded before or after.

Os Mutantes Jardim Electrico (1970) Like their other later albums, this 1970 effort does not get as much attention as the “Tropicália trifecta” of their first three releases. This is not entirely fair. True, much of the endearing wackiness and Dadaist mayhem inherent in their earlier work are gone. But it’s all replaced with new-found confidence, more disciplined song structures, and tighter playing. Recorded mostly in Paris, Jardim Electrico shows the “Brazilian Beatles” vying for an international audience. One song, “El Justiciero”, is in Spanish. Two others, “Baby” and “Technicolor” are in English; the former makes a fine addition to the two versions recorded in Portuguese during Tropicália’s heyday while the latter, an entirely new creation, sums up the band’s raison d’être more effectively than anything they recorded before or after.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely.

Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our review) during his and Gilberto Gil’s exile in London. While Gil also recorded some great work during this period, he wouldn’t fully regain his stride until being allowed re-entrance into Brazil in 1972. Expresso 2222 shows an invigorated yet wiser-for-wear Gil serving up his best work since his 1968 Tropicália masterpiece, Gilberto Gil. His music is as playful as ever, as evidenced by the celebratory “Back in Bahia”, but also more mature and introspective. From here, Gil’s work became less consistent, seldom reaching these artistic heights.

Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our review) during his and Gilberto Gil’s exile in London. While Gil also recorded some great work during this period, he wouldn’t fully regain his stride until being allowed re-entrance into Brazil in 1972. Expresso 2222 shows an invigorated yet wiser-for-wear Gil serving up his best work since his 1968 Tropicália masterpiece, Gilberto Gil. His music is as playful as ever, as evidenced by the celebratory “Back in Bahia”, but also more mature and introspective. From here, Gil’s work became less consistent, seldom reaching these artistic heights.

Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS.

Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS.

Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Further listening: Towards the end of his tenure in the Talking Heads, David Byrne became obsessed with the modern sounds of Brazil (these influences can be heard all over the Head’s final album, Naked, and his 1988 solo effort, Rei Mono). He founded a record label, Luaka Bop, which issued a various Brazilian artists sampler, Beleza Tropical, as its first release in 1989. Although it covered some more contemporary material, its emphasis was on material released in the ‘70s. Byrne stated that he hoped the record would do for Brazilian music what The Harder They Come soundtrack did for Jamaican music. While this was probably an unrealistic goal, Beleza Tropical did have an impact, and it’s doubtful that few outside of Brazil would know who Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil are had it not been released. Though missing some key artists and tracks, it provides a decent introduction for newbies. But it was the London-based Soul Jazz Records who really nailed it with their 2007 release, Brazil 70. Stuffed with tracks from all corners of the Brazilian renaissance of the 70s, it is probably the best compilation of its kind to be released so far. Here’s hoping for a second volume! —Richard P

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely. Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our

Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our  Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS.

Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS. Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.