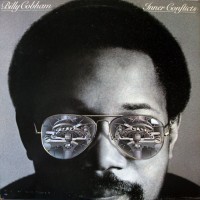

Conventional wisdom says that you should be leery of most jazz LPs from the late ’70s onward, but Inner Conflicts by ex-Mahavishnu Orchestra drummer Billy Cobham is an exception to that rule. Not that Inner Conflicts is a traditional jazz record. Nope. It’s actually a left-of-center fusion work with loads of Latin percussion and inflections—plus a mammoth electronic experiment that’s a phenomenal anomaly in Cobham’s catalog. Let’s get right to it, shall we?

Inner Conflicts‘ title track is by far the most impressive Heldon homage ever conceived by a jazz artist. (Google “Heldon/Richard Pinhas” and prepare to have your life changed for the better, if you’re not already familiar.) This beastly alien cut sounds like it could fit right in on Heldon’s infernal classic Interface, which came out in 1977. It finds Cobham drumming up a turbulent solar storm while also generating—with Moog Modular 55 programming help from John Bowen—a bizarre mélange of bleepy, gurgly synth emissions fit to score that mythical sequel to The Andromeda Strain. At almost 11 minutes, “Inner Conflicts” is a war of attrition on your nervous system, but totally worth the extreme exertion.

Inner Conflicts‘ remaining four songs are much more conventional, but interesting in their own right. “The Muffin Talks Back” is a flamboyant, eventful Latin jazz-funk fusion that hints at the gluttonous percussion fiesta—featuring Prince protégé Sheila Escovedo and her father Pete—to come on side two. “Nickels And Dimes” could be a rollicking, TV-cop-show theme in waiting, all blustery brass and woodwinds and frantic xylophone and marimba by Frank Zappa cohort Ruth Underwood. “El Barrio” starts as a lurching, heavily percussive, festive jam powered by whistles, congas, timbales, and other percussion instruments, before smoothing out into a undulating throb of Latin jazz marked by Cobham’s busy, potent kit work. The coolly burbling “Arroyo” showcases John Scofield’s well-modulated, Santana-esque shrieking guitar calligraphy.

Throughout the album, Cobham of course acquits himself as a powerful, kinetic, and inventive leader, asserting the world-class rhythmic skills that have made him desirable to so many musicians, including Miles Davis, John McLaughlin, Peter Gabriel, and Deodato. But it’s that cataclysmic wonder, “Inner Conflicts,” that remains most vivid in your shattered mind afterward. -Buckley Mayfield