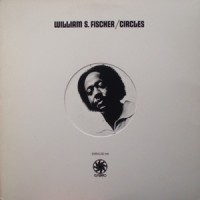

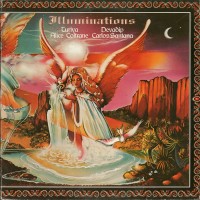

This may rankle some of his fans, but I’m going to say it anyway: Two of the best albums guitarist Carlos Santana ever played on didn’t come out under the aegis of his most famous band. For certain heads, the LPs the psych-rock deity cut with jazz legends John McLaughlin (1973’s Love Devotion Surrender) and Alice Coltrane (1974’s Illuminations) stand as his creative peaks. That these were released on a major label—good ol’ Columbia—and up until recently have been bargain-bin staples boggles the mind. However, one senses that the general public—and some critics who should know better—still aren’t giving these Eastern-leaning, mystical fusion works their due. I’m here to redress that injustice for the latter overlooked classic; maybe I’ll tackle the former some day.

As the title implies, Illuminations is all about transmitting blazing beams of enlightenment into listeners’ minds. It’s always a great idea to start your album with deep, extended “OOOOOHHHHHMMMMM” chants, especially if you’re a Platinum-selling artist. So listening to “Guru Sri Chinmoy Aphorism,” we gather that this music is going to be about god’s love, which is peachy if you’re into that sort of thing. Honestly, an agnostic like me just cares about the music, but whichever religious route it takes to get to the glory of Illuminations, all should tolerate it.

The one-two feathery punch of “Angel Of Air”/“Angel Of Water” is a profound unfolding of wonderment that preps you for the delights to come. In the former, Turiya and Devadip bestow upon us flute, bass, heavenly strings, pointillistic, crystalline guitar stalagmites, and cymbal splashes. The latter is a glistening pool of almost New Age-y bliss (not a diss, by any means), as these world-class musicians—including Santana electric pianist Tom Coster, and Miles Davis comrades Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland—summon some of the most delicate, celestial aural tapestries in their blessed careers. You know how Kris Kristofferson had a song called “Sunday Morning Coming Down”? Well, this is Sunday morning going up music. You feel like you need more than one heart to appreciate the loving feeling emanating from this song. Side 1 closes with “Bliss: The Eternal Now,” which sounds like something that could’ve appeared on Coltrane’s Lord Of Lords. This is a heroic fanfare of orchestral ambience that portends glimmers of a brilliant new dawn for humankind… but we all know how that turned out.

The album’s peak comes with the 15-minute “Angel Of Sunlight,” the closest thing to Love Devotion Surrender on Illuminations. Elevated by Prabuddha Phil Browne’s cosmic tamboura drones and Phil Ford’s rapid tabla slaps, “Angel Of Sunlight” charges pell-mell into the fiery orb as Santana Santanas at his most Santana-esque. His six-string calligraphy arcs and darts across the sky with grandiloquent fluidity, wailing like some creature beyond any of our thousands of our so-called gods’ imaginations. Then, as if your ears weren’t surfeited enough with pleasure, Coltrane’s Wurlitzer solo flares in delirious, rococo siren tones within the golden-hued tumult. This track is a sonic analogue for the cover, a supernatural lavishment of benedictions from players tilting toward transcendence. What follows can only seem anti-climactic, but “Illuminations” is a denouement of ethereal solemnity and grace. It’s the dignified breather you need after “Angel Of Sunlight”’s ravenous enrapturing.

There’s probably a copy of Illuminations sitting in a used bin near you for under $12. Go forth and grip. -Buckley Mayfield