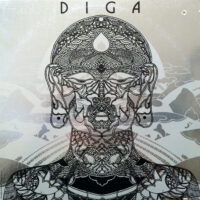

Featuring Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart and tabla master Zakir Hussein (Shakti, Shanti, etc.), Diga Rhythm Band recorded only one album, but it’s a doozy. Among Dead diaspora records, Diga ranks near the top, along with Garcia, Hooteroll? (by Howard Wales and Jerry Garcia), and Ned Lagin’s Seastones.

With members in the double figures, Diga Rhythm Band have the tools for a percussion orgy, with Ray Spiegel’s vibes and Jim Loveless’ marimba providing melodies. Other instruments struck and plucked include congas, bongos, gong, timbales, duggi tarang, and tar. Diga is a true East-meets-West hoedown, and the beats often come at you fast, complexly, and in a multitude of timbres. Incredible Bongo Band had nothing on these quick-wristed badasses.

Discogs has appended genres such as “jazz,” “folk,” “world,” and “free improv” to Diga, but the album transcends categorization. It sounds more like a pure expression of creativity that comes from hitting various percussion instruments for the sheer transportive hell of it. For example, “Sweet Sixteen,” which starts with a luscious melody on vibes and bulbous and swift tabla slaps; when Hart’s drums kick in, the track takes flight. Later, we get a big percussion breakdown and then a flamboyant finale. Talk about a mood-elevator…

At nearly 13 minutes, “Magnificent Sevens” exemplifies the record’s brilliant dynamics, its surging power rushes and dramatic rests. Moving from eerie ambient mode—with distant gong hits and murmuring vibes—to mind-bogglingly mercurial slaps, DRB produce a veritable hail-storm-on-a-tin-roof scenario. Additionally, they definitively prove that vibes coupled with tablas is a divine confluence of tonalities. The LP’s other epic, “Tal Mala” also showcases DRB’s inexhaustible rhythmic inventiveness.

The two tracks on which Jerry Garcia guests are the shortest and most accessible to Western ears. “Happiness Is Drumming,” stands as the most conventionally “rock” song here; it presaged “Fire On The Mountain” from the Dead’s 1978 album, Shakedown Street. Garcia’s languid, fluid guitar stars on this laid-back beauty, with Hart doling out heavy-handed snare hits. Jerry alternates between stun-gun guitar and jazzy, pointillistic mode on the Spiegel composition “Razooli,” which also features a loopy, undulating marimba motif over swiftly pattering congas.

Diga isn’t exactly rare, but it ain’t too common, either. I scored my copy at Jive Time for $15 about a decade ago. The price may have crept up since then. Whatever the case, it’s pretty much a bargain at whatever sum you find it. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.