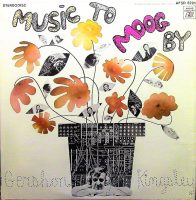

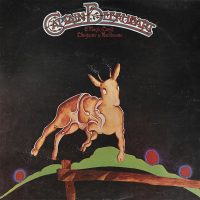

This album seemingly just materialized from the vapors of that heady year of 1967. It’s a freakish one-off, a slapdash, communal psychedelic happening magicked into existence by British graphic designers Michael English and Nigel Waymouth, with help from producer Guy Stevens and many other ringers and hangers-on (Groundhogs’ Tony McPhee, Tyrannosaurus Rex’s Mickey Finn, and some bloke named Brian Jones are in the mix). If the music lived up to its spectacular cover, it would be one of the greatest records of all time. It’s not quite in that echelon, but it is mighty great—especially for visual artists dabbling with music.

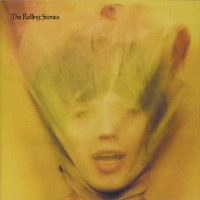

“H-O-P-P-WHY” launches the album with a deep, primal chug that’s bolstered by barrelhouse piano—an approach that foreshadowed the Rolling Stones side project Jamming With Edward! It also sounds not too far off from what the Mothers Of Invention were doing on “Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet” from 1966’s Freak Out! LP. The spirited, chanting vocals and harmonica here recur throughout Featuring The Human Host And The Heavy Metal Kids, and I’m not complaining.

The awesomely titled “A Mind Blown Is A Mind Shown” is a tambourine-, harmonica-, and bongo-heavy hippie hoedown that nicely sets the scene for the LP’s zenith, “The New Messiah Coming 1985.” This cut is perhaps the biggest influence on krautrock demigods Amon Düül I; it’s a hypnotic mantra riding a basic, folkadelic, acoustic-guitar riff, unison chants (“WE ARE!”… “I AM!”), bells, finger cymbals, awesome gong splashes, and a clodhopping caveman beat. Honestly, if the whole album had been just 40 minutes of this, it would be a stone classic and everyone who heard “Messiah” would have a hard time not basing a religion around it. As it is, the song fades out right when it should be intensifying. Oh, well… maybe next lifetime. “Aoum” is more a kundalini-yoga chanting exercise than a song, but what do you expect from a track named after the sacred sound that signifies the essence of ultimate reality?

“Empires Of The Sun” is a relentless, joyous romp that fills all of side 2. Hapshash throw in everything they’ve got in this maximalist über-jam, which appears to be tumbling down a mountainside in an avalanche while all of the group’s friends whoop, holler, intone “hari krishna” and “om,” and fake orgasms to the tumultuous freakout. There are also some of the wildest flute or ocarina trills you’ll ever hear. It’s a peak-time burner, for sure, and a helluva way to end a debut album.

Hapshash’s second full-length, Western Flier (1969), sounds little like this dazzling gem, going off in a corny, song-oriented direction that doesn’t play to their strengths. It’s shockingly bad, one of the biggest sophomore slumps in rock history. Little wonder Hapshash split after this, but wow, what an initial splash they made. -Buckley Mayfield