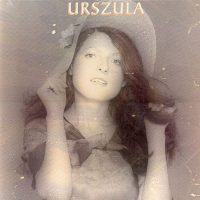

Yoko Ono, Linda Sharrock, and Urszula Dudziak—behold the holy trinity of extreme female vocalists, gentle reader. The latter is the undisputed queen of Polish jazz singers, using her electronically treated five-octave range to embroider compositions that encompass a cappella fantasias, rococo fusion workouts, and spacey funk. Dudziak’s gift for improvising enchanting and unpredictable patterns with her quirky and delicate delivery turn her records into minefields of flighty frissons.

Produced by husband and renowned fusion violinist Michał Urbaniak, Urszula kicks off with “Papaya,” a ridiculously effusive disco-jazz number featuring Dudziak nimbly scatting in her upper register, which is very high, indeed. It’s almost impossible not to dance and laugh yourself silly simultaneously. “Mosquito” follows with methodical, elastically funky soul, over which Dudziak babbles like a European Sharrock on a track reminiscent of Larry Young’s Fuel. An extra boost comes from Miles Davis sideman Reggie Lucas’ guitar solo, which flares in the same extravagant zones as Larry Coryell and John McLaughlin’s. “Mosquito Dream” is a sparse, a cappella chantfest somewhere between Joan La Barbara and Diamanda Galás; it’s geared to freak you the fuck out. “Mosquito Bite” closes the insect quadrology with UD going HAM at imitating an analog synthesizer, à la Annette Peacock. Joe Caro’s scorched-earth guitar riffs propel this song into the fusion/porn-flick-score hall of fame (admittedly a narrow niche).

The second side can’t quite equal the first’s bizarre iconoclasm, but it’s still full of loopy joie de vivre, circuitous songwriting, and frou-frou fusion frolics. Special mention goes to “Funk Rings,” which belongs in the pantheon for weirdest funk tracks of all time, as Dudziak splutters rhythmically over what sounds like one of the stranger cuts off Herbie Hancock’s Man-Child (another 1975 LP reviewed recently on this blog).

Make no mistake: Urszula Dudziak is a unique talent. If you seek otherworldly beauty and unconventional vocal timbres and tricks, she’s your woman. (Check out other titles like Newborn Light and Future Talk, as well as her contributions to Urbaniak’s Inactin, for further enlightenment.) -Buckley Mayfield