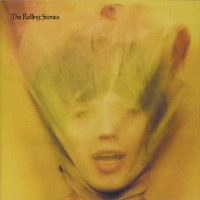

The fact that you often see Harvey Mandel’s albums in the used bins is yet more proof that the world’s full of fools. The Detroit-born blues-rock musician is a guitarist’s guitarist who played with some of the best blues-rock musicians of the ’60s (Canned Heat, John Mayall, Charlie Musselwhite) and was thisclose to joining the Rolling Stones. You can hear Mandel auditioning for the slot given to Ron Wood on 1976’s Black And Blue, on which Harv knocked it out of the park on “Hot Stuff” and “Memory Motel.” I can’t be the only one who thought Mick and Keef blundered with their pick (pun intended).

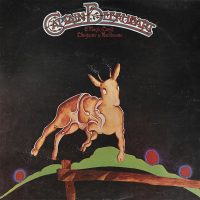

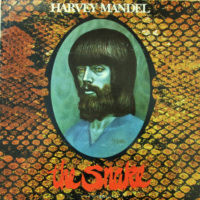

Anyway, Mandel’s string of albums from the late ’60s to the mid ’70s is strong, with The Snake being its peak. Right from go, “The Divining Rod” alerts you to Mandel’s six-string mastery, with its dynamic, swerving rock powered by righteous cowbell. He wrings serpentine, silvery lines of dazzling intricacy and elasticity, and you can tell Meat Puppets’ Curt Kirkwood was listening intently. The zig-zagging, Gábor Szabó-esque jazzadelia of “Pegasus” assumes a Romani tinge thanks to Don “Sugarcane” Harris’ spirited violin coloration. As for “Peruvian Flake,” I learned from the Urban Dictionary that the title’s a slang term for cocaine, so it’s apropos that this song’s quicksilver rock of mind-boggling technical proficiency. It’s kind of shocking that Steely Dan didn’t hire Mandel after this came out.

Some other highlights include “Ode To The Owl,” a moving blues-rock solo guitar tribute to Canned Heat’s Alan Wilson, who died in 1970 at the tragically young age of 27 and “Levitation,” whose sly jazz rock is elevated by Charles Lloyd’s flute, Freddie Roulette’s sublime, pointillistic steel guitar solo, and Kevin Burton’s flamboyant soul-jazz organ solo. My fave cut is “The Snake” (a slightly less sublime and psychedelic version appeared on Mandel’s 1968 debut LP, Christo Redentor). This might be the coolest, most funkadelic track in Mandel’s canon, and as I’ve discovered as a DJ, it segues very well into Herbie Hancock’s “Hang Up Your Hang Ups.” Mandel saved the fieriest for the last with “Bite The Electric Eel.” This is a fried blues-rock jam that can hold its own with Peter Green’s The End Of The Game. The song’s full of staggering showboating, but there’s nothing at all annoying about it.

I paid $1 for my used copy of The Snake, but as it’s the zenith of one of America’s most virtuosic and tone-smart blues-rock guitarists, the album’s worth at least 30 times that. Hot stuff, indeed. -Buckley Mayfield