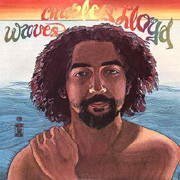

One sees a lot of Charles Lloyd LPs in used bins—especially Forest Flower, Love-In, and Journey Within. That ubiquity suggests that the American jazz saxophonist/flautist had a spasm of commercial success, followed by a substantial disenchantment with his popular releases. It’s a common phenomenon, and it often pays dividends for crate-diggers decades later. While Waves isn’t quite as easy to find as the aforementioned records, it does pop up with some frequency for fairly low prices. I’m here to suggest that you should snap it up when you see it, as it punches way above its price point.

Like a handful of serious jazz artists, Lloyd intermingled with rock royalty at a time when jazzers and hippies often shared similar worldviews and aesthetics. That’s how Lloyd ended up corralling Beach Boys members Mike Love, Al Jardine, Carl Wilson, and Billy Hinsche and the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn to make Waves. You can hear these West Coast rock gods in full flower on album opener “TM” (yes, it’s a blissful paean to transcendental meditation, and it sure sounds like it). Add the fantastic Hungarian guitarist Gábor Szabó to the mix and you have a gilded gem of a tune that you can imagine appearing on Friends, 20/20, or Surf’s Up, what with its patented honeyed, intricate vocal interplay by those Beach Boys cats. Plus, Pamela Polland is no slouch on lead vox.

“Pyramid,” cowritten by guitarist Tom Trujillo, is an epic psych-jazz ramble with plenty of Lloyd’s flute dazzlement and a guitar/bass duel that makes me think of Wolfgang Dauner’s astounding Et Cetera album from 1970. “Majorca” is pretty much a continuation of “Pyramid,” but with Szabó unspooling rococo guitar filigree all over the shop. These two songs will make you feel about 67 percent more sophisticated than you actually are. Let it be known that this is one helluva side one.

Side two kicks off with the nine-minute “Harvest,” another Szabó extravaganza; it’s jaunty, fleet hippie jazz spiced by Gábor’s pointillistically pretty guitar origami. On the gorgeous psych-jazz meditation “Waves,” McGuinn exudes restrained lustrousness on his 12-string guitar while the melody recalls Todd Rundgren’s “I Saw The Light”—which also came out in 1972; weird. The triptych “Rishikesha” concludes Waves with a gentle psychedelic reverie that strives for a peace beyond understanding. Whether you think it attains that exalted state depends on your own tolerance for long-haired utopian soundtracks and Mike Love’s quasi-mystical lyrics. Luckily for me, I at least have a healthy appetite for the former.

Waves is a testament to Lloyd’s aptitude for adaptability. He proved that a respected jazz musician could smoothly transition into the precarious freak zone of fusion and hippie rock and create a lasting work—even though too few people realize it. -Buckley Mayfield