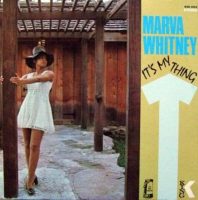

It’s My Thing is the closest thing we’re ever going to get to a female-fronted James Brown album. The fact that it was cut in 1969 when the Godfather Of Soul and his crack band the JBs were absolutely on fire during one of their creative peaks means that It’s My Thing is an essential document of hard-hitting soul and funk and the occasional bravura ballad.

The album kicks off with a cover of the Isley Brothers’ über-funky and precise “It’s Your Thing,” buttressed by Whitney’s brazen vocal sass and the JBs’ ultra-tight funk churn and roaring horn surges. There’s a good reason this song’s been sampled over 70 times, including by Public Enemy, N.W.A., Ice Cube, and EPMD. “It’s My Thing” is so good, it needed a second part on this record. Speaking of oft-sampled tracks, “Unwind Yourself” has had its opening break sampled by the 45 King for the club smash “The 900 Number” and by Aphex Twin for “Taking Control,” among many others. This dance-floor heater struts with a massive swagger.

On the tight, punchy, and greasy R&B of “Things Got To Get Better (Get Together),” Whitney proves she’s an overwhelmingly passionate diva to whom you’d better bring your A+ game if you want a chance of getting together with her. In a similar vein, “What Kind Of Man” flexes classic, boisterous soul on which Whitney shows she’s the epitome of the assertive soul diva. “You Got To Have A Job (If You Don’t Work, You Can’t Eat)” is a paean to productivity and industriousness, with numerous extravagant shout-outs to Maceo Parker and it foreshadows the killer groove from Brown’s “Talkin’ Loud And Sayin’ Nothing.”

Some anomalies include “In The Middle,” an extremely cool funk instrumental written by saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis and Bud Hobgood that you wish were at least twice as long as it’s 2:45 and the heart-on-sleeve ballad “If You Love Me,” which is the only time I’ve heard a sitar on a James Brown production. The fleet and nimble “I’m Tired, I’m Tired, I’m Tired” is one of Brown’s most moving and eloquent compositions, a soulful condemnation of racism and a plea for racial justice. On the sentimental, strings-enhanced ballad “I’ll Work It Out,” Marva sings her huge heart out. She just lays it all out there, demonstrating that she’s damn near the equal of her mentor.

(It’s My Thing has been reissued several times over the decades, with the last legit-looking one coming from the UK label Soul Brother in 2015.) -Buckley Mayfield