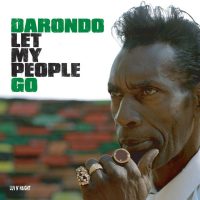

The perfectly named Wendy and Bonnie Flower made one great album, Genesis, and then dispersed after Skye Records went bankrupt following its release and its producer Gary McFarland died as they were planning their sophomore LP. The Flower sisters thereby became members of the cherished one-and-done club, which includes Skip Spence, Billy Nichols, Ceyleib People, Friendsound, the United States Of America, McDonald & Giles, and Baby Huey, to name a mere handful. That Wendy & Bonnie were 18 and 15, respectively, when Genesis came out adds to the luster of their legend.

These teens obviously were extremely precocious songwriters and singers, but Genesis likely wouldn’t have ascended to its burnished status without contributions from a cast of stellar session musicians such as drummer Jim Keltner, keyboardist Mike Melvoin, and guitarist Larry Carlton. They all play their asses off for these gifted upstarts, and it’s goddamn precious to witness. Production from bossa-nova/jazz vibraphonist McFarland and label support from Skye co-owner and Latin-jazz percussionist Cal Tjader, who’d heard and loved the duo’s early demos, further bolstered the recording sessions.

Genesis busts out of the gate with “Let Yourself Go Another Time,” a seductive, low-slung rocker with the ladies’ unison vocals racing with Michael Lang or Mike Melvoin’s kozmigroove keyboard whirlwinds, like Ray Manzarek on amphetamines. Auspicious! “The Paisley Window Pane” dips 180º in the opposite direction with a delicately beautiful and morose ballad buttressed by Carlton’s languid acoustic guitar picking. Wendy and Bonnie’s intertwining vocals are exquisite, full of Karen Carpenter-esque yearning. “I Realized You” is a ballad that shifts into a featherlight psych-pop brooder somewhere between the 5th Dimension’s pensive pulchritude and Laura Nyro’s sophisticated chords. It’s yet more proof that the Flower sisters are sophisticated beyond their years. “By The Sea,” a spare yet complex ballad illuminated by ice-crystal piano coloration, was covered by Stereolab’s Lætitia Sadier and sampled by Super Furry Animals.

Things pep up on “You Keep Hanging Up On My Mind,” a Margo Guryan-esque sunshine pop tune with a few clouds around the edges. During the poised, rocking coda, Carlton and bassist Randy Cierly go off on brilliant serpentine runs. The uptempo, driving psych of “It’s What’s Really Happening” approaches the sublimity of the United States Of America, with bonus gorgeous vocal harmonies. The baroque, lacily beautiful psych of “Five O’Clock In The Morning” could make the dudes in the Left Banke nod in appreciation. The understated psych of “Endless Pathway” highlights the radiance of Wendy and Bonnie’s unison vocals, but they’re just different enough to create a ghostly undercurrent. Utterly beguiling, “Children Laughing” is a swaying lullaby pitched somewhere between the Millennium and Broadcast. Genesis ends with perhaps its strongest cut, “The Winter Is Cold,” a rocker with chill-inducing, contrapuntal vocal harmonies. The song has moments of seriously groovy psychedelia, with Carlton unleashing distorted solos that recall Howard Roberts’ work with Electric Prunes circa Release Of An Oath.

I recently saw someone online selling an original pressing of Genesis for $160. Luckily, Sundazed has reissued the LP three times in the last 14 years. A record this gorgeous should never be out of print. -Buckley Mayfield